Editor’s Note

This is Part One of a two-part series that came out of the “Our Kids” reporting project. Our Kids is a project of the Broke in Philly reporting collaborative, which examines the challenges and opportunities facing Philadelphia’s foster care system.

So, why Philadelphia? While we generally report mostly only on issues in Los Angeles and around California, this two part series — which originally ran in NEXT CITY — skillfully points beyond itself to the destructive and disproportionate treatment that too many Black families, Indigenous families, and Latinx families all over the nation, including in California — and, yes, in Los Angeles — are experiencing when they come in contact with the child welfare system.

Thus we wanted to bring this important series to WitnessLA’s readers.

So read on.

Reimagining a foster care system that errs on the side of protecting children, but disproportionately investigates and punishes Black families more for economic hardship than harm.

Story by Steve Volk

Illustrations by Dylan B. Caleho

Shortly after Christmas, Kyeesha Lamb’s baby boy fell out of bed. She and her boyfriend had co-slept with the four-month-old child that night and awakened to his crying.

Quickly, Lamb picked the child up from the hardwood floor, soothed him back to sleep, checked on him in the night, and by morning, the experience looked like an inexpensive lesson: the baby showed no ill effects at all. Over the next couple of days, however, Lamb noticed her son used his right arm very little and sometimes held it tightly to his side. “He didn’t seem to be in any pain unless we tried to move his arm around,” she says, “but I didn’t like it.”

Lamb, 24, was already raising another boy, just 16 months old, and knew to keep a close watch on the newborn, to see if he improved. But over the next few days, he continued favoring the arm and even went through an odd crying episode — a spell that convinced Lamb she needed to take him to the hospital.

The staff at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania asked her what happened, appeared supportive, and then informed her that the doctor had ordered a full skeletal x-ray.

Shortly after that, the tone of the visit changed. The radiologist discovered two possible injuries — a break in the baby’s arm, which appeared consistent with the fall Lamb described; and a possible second break in her baby’s leg, too, which looked older. Lamb could not explain that second potential injury. There had been no earlier accident.

Lamb expressed concern and took solace in the doctor’s admission that x-rays were sometimes uncertain.

“They said, sometimes, in babies, they see what looks like a fracture in the x-ray, still healing,” says Lamb. “But it could also be just how the baby’s bones are growing.”

To confirm a break, staff told her, a new set of x-rays would be taken in a few weeks. If the new images showed fresh bone growth around the supposed fracture site, they’d know the radiologist had discovered a bone in the process of healing. If no new growth appeared, they’d know there had never been a break at all.

The problem, hospital staff informed her, was that the suspected second break suggested possible child abuse, giving them no choice under the law but to report her to the Department of Human Services. Fear brewed in Lamb’s stomach as she defended herself. Then a DHS caseworker arrived, questioned her, and took both children into custody.

Now, months later, Lamb’s experience of the child welfare system continues. The second set of x-rays cleared her, showing no new growth at the suspected fracture site — proof that there was no break in the baby’s leg. Nevertheless, DHS informed her that they would keep her kids in custody until a full hearing could be held.

“I didn’t understand how this was possible,” says Lamb, recalling the moment she heard the news. “I was like, ‘I didn’t do anything wrong. You know that now, and you’re still keeping my kids?’”

Lamb’s story, however, isn’t that unusual. Built to err on the side of caution for kids, the child welfare system often manifests as a punitive and intrusive force, particularly toward Black families, who are statistically more likely to be referred for investigations and more likely to have their kids taken into foster care when compared to white families. As a result, reformers and abolitionists are demanding that the system be reformed, even wholly reimagined. They frame this cause in the language of the Black Lives Matter movement — a cry to preserve Black families against a system built to separate them.

A 2010 paper in the journal Pediatrics examined 3,063 cases of infants who suffered traumatic brain injuries at 39 different hospitals. The authors found that infants in black families, and infants in families who did not have government health insurance, underwent greater testing than did white infants who suffered similar injuries. Children in white families, however, were more likely to be determined victims of child abuse if a skeletal survey was ordered. Illustration by Dylan B. Caleho

Research uncovers patterns of bias

Last summer, worldwide news broadcasts of George Floyd’s murder by a white Minneapolis police officer triggered racial justice protests across all 50 states and around the globe. Child welfare advocates and activists were among many who felt the horror of those images personally.

“The foster community obviously has a disproportionate number of Black people in it,” says Constance Iannetta, founder of Foster Strong, which seeks to improve child welfare practices and raise public awareness, “and I knew that tragedy was really going to resonate across our community.”

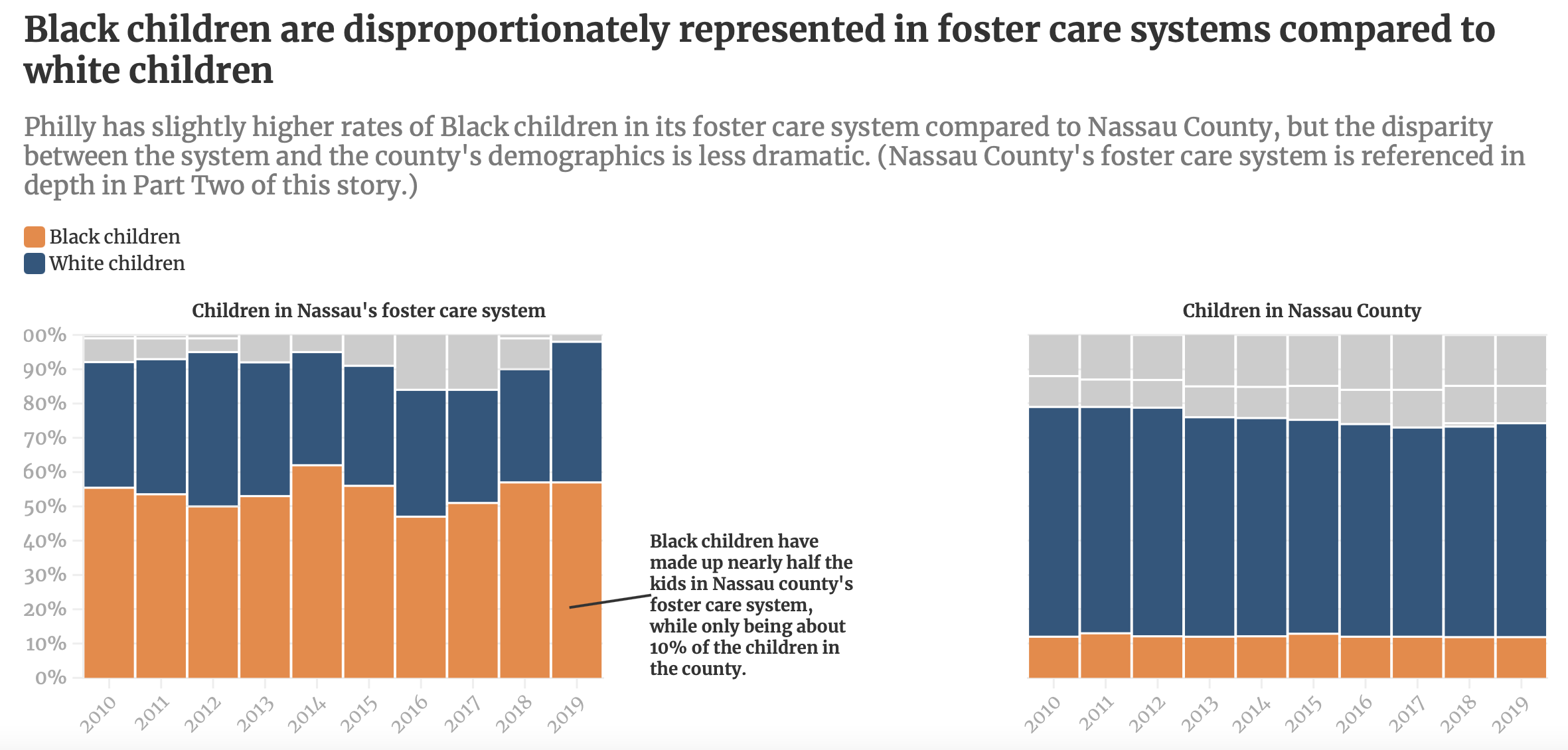

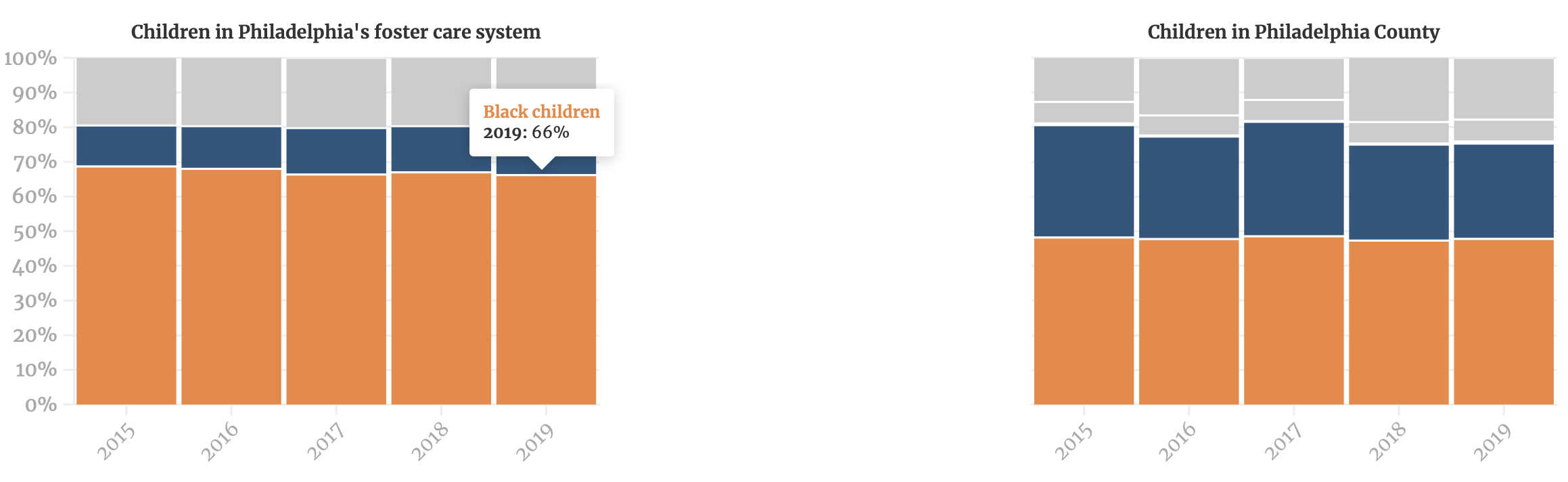

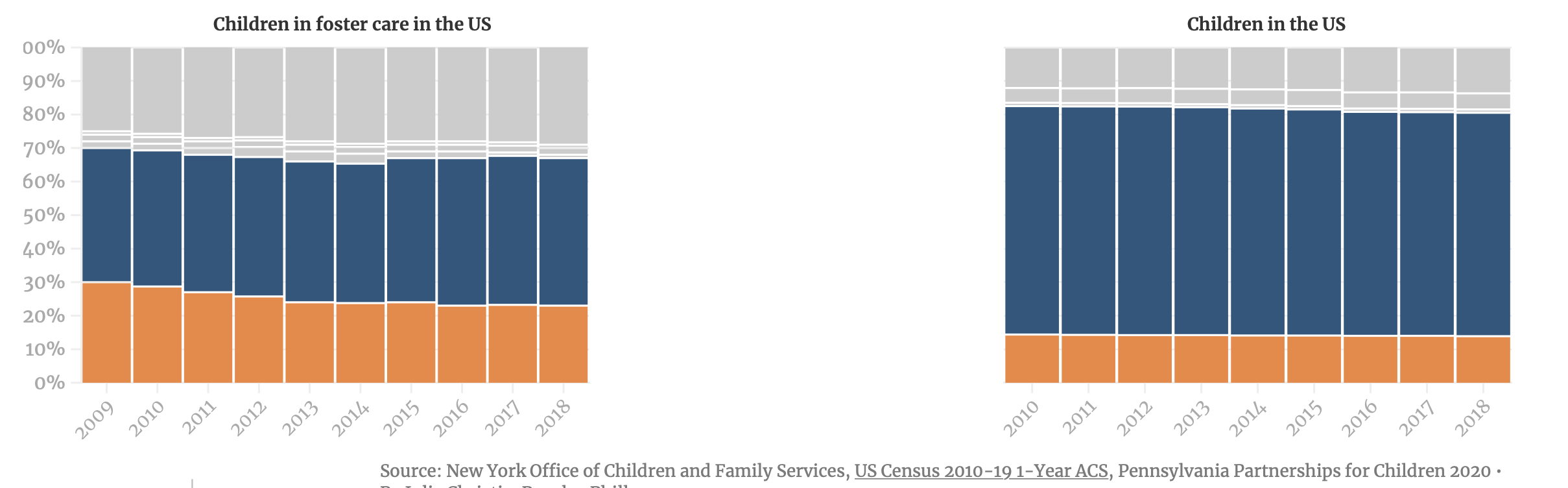

Black people comprise about 13 percent of the total United States population and 25 percent of the youth in foster care. In Philadelphia, where Lamb lives, the disparity is likewise dramatic, showing Black people comprise 42 percent of the population and 65 percent of the youth in foster care.

For at least a decade, government officials and child social workers alike have been talking about how to address this disproportionality, which affects Indigenous and, in some states, Latino families as well. Of course, some still deny that the problem even exists. Elizabeth Bartholet, a Harvard law professor, has maintained over the years that Black people are more often involved in child welfare because “maltreatment rates” are higher in the Black population. Other researchers counter that this argument represents both magical thinking and circular reasoning.

“We’ve seen clear research throughout American society, not just in law enforcement but [in] banking and housing, that racism exists,” says Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, which has been advocating for decades to drastically reduce the number of kids in foster care. “But social workers are somehow immune from that? It doesn’t make any sense.”

Further, Bartholet’s opponents point out that maltreatment rates are based on decisions that people make to report, investigate and judge families. Racially biased input will yield a racially biased output.

The papers showing evidence of racial bias in the system run deep. A paper published in January 2021 in Children and Youth Services Review surveyed the existing studies of child protective services investigations and race and determined that Black families are subjected to greater scrutiny and harsher judgment at virtually every stage of contact, including disproportionate reports to CPS, subsequent investigations and child removals.

Multiple studies also have shown that Black families are less likely than white families to receive in-home services, also called “preventive services,” which are intended to keep families together. A 2016 study published in Public Health Nursing suggested the reason why. The authors looked at 62,499 neglect or abuse cases across five states and found that child welfare professionals often regarded Black parents as less likely to change.

University of New Hampshire social work professor Vernon Brooks Carter looked at 418 substantiated cases of a lack of supervision; of the families represented in the study, 60 percent were white and 31 percent were Black. Carter found that white kids were more likely to be inadequately supervised by their parents — left at home alone, for instance, while mom runs to the store. But Black children under similar circumstances were more than three times as likely to be removed from their parent’s care.

Lamb’s particular case also fits the pattern of racial bias uncovered by past research.

In fact, a 2010 paper published in the journal Pediatrics that documented racial bias in the child welfare system focused on American hospitals. The study examined 3,063 cases of infants who suffered traumatic brain injuries at 39 different hospitals. The authors found that infants in Black families, and infants in families who did not have government health insurance, underwent greater testing — such as the skeletal survey ordered of Lamb’s child — than did white infants who suffered similar injuries.

Children in white families, however, were more likely to be determined victims of child abuse if a skeletal survey was ordered, suggesting that doctors engaged in heavier scrutiny of white families when it was truly warranted.

Dr. David Rubin, the paper’s senior author and a pediatric researcher at Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania (CHOP), summed up the obvious conclusion at the time: “These results raise concerns that different thresholds for suspicion of child abuse were being used for children of different races and economic levels,” he said.

The parallels with law enforcement

What is most striking about the findings of racial bias in child welfare, however, and what activists and reform-minded researchers have seized on, is how closely these examples of bias track with comparable research on bias in policing.

For instance, other papers similar to the brain injury study at CHOP have shown that even when white children are brought to hospitals with more significant injuries, they are less likely than their Black counterparts to undergo further abuse assessment. In the same vein, law enforcement statistics show that police are more likely to shoot and kill Black people, whether armed or unarmed, and more likely to stop and search Black motorists. However, white motorists who are detained and searched by highway patrol officers are more likely than their Black counterparts to be in possession of illegal contraband. This particular finding parallels cruelly the decision of those in authority to conduct more skeletal surveys of Black children and suggests that doctors and cops alike tend to investigate white people when meaningful indicators suggest that they should — but seem to investigate black people because they’re Black.

“We’ve seen this throughout American history,” says Erin Miles Cloud, co-founder and co-director of Movement for Family Power, a New York nonprofit focused on deep reforms, even abolition, of the child welfare system. “Black people and Black families face this kind of racism across society from public institutions. Child welfare reform, like Black Lives Matter, is a call for equity and social justice.”

Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services has a general policy of not commenting on specific cases, to preserve the parties’ right to privacy, and declined a request to comment on Lamb’s case. They are, however, deep into a study that analyzes racial disproportionality in their system, in collaboration with University of Pennsylvania researchers and Casey Family Programs, a philanthropic organization devoted to child and family welfare. Results are expected to be released publicly this summer or fall. A report DHS compiled on Phase One of the project, and supplied for this story, is clear-eyed, noting Philadelphia’s rate of “Black children in placement was twice that of white and Latinx children” and framing the study ambitiously as an attempt to “reduce out-of-home placement and eliminate disparities.”

Unlike calls for police reform, however, calls to transform the child welfare system are mainly circulating among industry professionals and advocates, and have not yet gained traction in widespread public debate.

Philadelphia city councilman David Oh has been surprised by the lack of public awareness on the subject. “The racial bias in child welfare is evident,” says Oh, who is co-chairing ongoing special committee hearings investigating the workings of Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services — hearings where Lamb offered testimony about her experience. “And there are activists working in this space. But in the popular media and public consciousness, I do not think the ‘social justice warriors’ have really seized on the connection that exists between this cause and the Black Lives Matter movement.”

As the racial justice protests continued across the country last summer, and poll numbers showed Black Lives Matter gaining support, however, foster care activists took note.

“There are a lot of us talking about it,” says Iannetta, “Like, how can we learn from this?”

Iannetta’s main takeaway is that BLM became a political constituency, gathering numbers and making it clear that they would vote based on whether candidates embraced or rejected their platform. Advocates for change in child welfare, she says, must do the same, advocating through groups such as Foster Care Alumni of America for their issues, and insisting that elected officials pay attention. The constituency Iannetta identifies is potentially massive. More than 400,000 U.S. youth are in foster care at any given time, and 250,000 or more exit the system annually, exponentially increasing the number of Americans who are touched by the system — including parents and loved ones — into millions.

But the fight to reform child welfare faces a significant challenge. Unlike incidents of police violence, which can sometimes be documented on cell phone cameras, child welfare meetings are typically held behind closed doors. That confidentiality protects the children, but prevents any public accountability for decision making, and makes the stories that do leak out, like Lamb’s, that much more valuable.

Exonerated but penalized

After the second set of x-rays came back, Lamb texted her court-appointed lawyer, Patricia A. Cochran.

“Does [sic] the hospital records mean anything?” she writes. “Like it’s honestly what they’ve been waiting on and they’re in my favor.”

“I know,” Cochran replies.

Almost three weeks had passed since Lamb lost her kids, and hours more since the news had come confirming that there was no break in the baby’s leg. By this time, Lamb felt a deep sense of gratitude to the foster family taking care of her children. They supplied her with a steady stream of cell phone pictures and information about her kids. Still, not knowing what her babies were doing at every given moment, lacking their company and touch, left her feeling a constant hollowness and pain. Even though DHS knew the x-ray results revealed no prior second injury, that day and night passed without word.

Family reunifications can take time. The caseworker and their supervisors, along with the child advocate appointed by the court to represent kids in dependency cases, must all agree that reunification is the best course.

Finally, the following morning in late January, Cochran texted to let Lamb know that they had decided her children could come home.

“Yayyyy when,” Lamb writes back. “This amazing newssss.”

“I’m sure they will call you,” her attorney writes.

Five hours passed. Then, her phone pinged with another text from her attorney: “DHS is apparently having second thoughts,” Cochran writes. “The decision to reunify will be made at the hearing on 2/16. I’m very sorry.”

Nearly three more weeks. Lamb’s spirit plummeted like an elevator severed from its cables. Second thoughts? she wondered. About what?

From there, the text thread skips across possibilities:

“Do both of the children have beds?” her attorney asks. “Co-sleeping is considered dangerous. You have to agree to no more co-sleeping. … Are you doing the parenting class?”

Lamb confirms that she was complying with DHS’s requests, agreeing to personal therapy sessions and enrolling in a parenting class. When her attorney had no explanation for the delay, Lamb made calls on her own, learning from a social worker assigned to her case that DHS had developed concerns about potential domestic violence.

“There is no domestic violence,” she writes to Cochran. “How can they just say that?”

“I have no clue,” Cochran writes back. “It’s not mentioned in the petition.”

“I’m confused as to what’s happening,” writes Lamb.

“We have to wait until 2/16.”

“I feel taken advantage of and hopeless. How can they do this?”

“I have nothing to tell you. We have to wait until the hearing.”

Regular participants in the child welfare system say these types of twists, sudden and sharp, are common. “They come in with an allegation, and if that doesn’t pan out they look for something else,” says one child welfare worker, who regularly observes dependency court and asked not to be named, for fear of losing employment. “They don’t really need any evidence.”

In this instance, a DHS investigator had interviewed a relative of Lamb’s boyfriend, who raised the specter of possible domestic abuse. According to the caseworker, the relative told the investigator that Lamb’s boyfriend had related that the pair had been fighting when the baby fell off of the bed.

Lamb and her boyfriend vigorously deny this account, saying they have been feuding with this family member. DHS’s argument is thin — an allegation, from a disgruntled relative, with no evidence to back it up — yet in dependency court, that is often enough to keep families apart. The episode reveals a disturbing dynamic in the child welfare system, which simultaneously portrays Lamb as a victim and punishes her for it by taking away her kids.

“I had done everything right,” she says. “My baby fell. I watched him, I took him to the hospital. The hospital ended up saying I was right. But they were still keeping my babies? It didn’t make any sense.”

Longtime child welfare professionals say that by choosing to speak out, Lamb risks backlash from DHS and potentially from the courts. Child dependency proceedings are closed to the public and media in most jurisdictions, Philadelphia among them, to protect the privacy of children. Case records, such as court transcripts, are also typically sealed.

Further, child welfare caseworkers are usually given a kind of provisional benefit of the doubt. Dubbed the “invisible first responders,” they sometimes encounter truly horrific situations, in the bleakest corners of human experience. Industry-wide, turnover rates hit 30 percent annually. The hours are long; many workers regularly log 60-hour weeks or more to cope with oversized caseloads. And they make extraordinarily difficult decisions every day about the futures of the families they encounter — knowing that whatever benefit of the doubt they have received will disappear if they ever investigate a family, determine to keep them together, and then a child in that family winds up severely injured or dead.

Though occasional stories appear in the media that show child welfare caseworkers in the field, the black box of privacy built around child protection cases ensures that caseworkers are rarely seen. Lamb, however, having navigated through a system that has left her feeling powerless, sees going public as part of the effort she can make to try and save her family. She verified as many details as possible — the skeletal survey, the petition DHS filed to justify taking her children, the finding that the follow-up x-rays showed no leg injury — providing to Next City the court and hospital documents and copies of text conversations with her attorney. Her decision to speak out provides a rare if imperfect window into the operations of a system that functions differently than the public may expect.

Media accounts about foster care typically list the number of youth in care — about 4,500 in Philadelphia alone — and note they were victims of “abuse and neglect,” words that trigger associations with horrific deaths, such as the tragic torture and murder of Gabriel Fernández, in Los Angeles, covered in a recent Netflix docuseries. In light of such high-profile cases, an analysis of the numbers reveals a surprising reality — that physical or sexual abuse are among the less common reasons for child removals, accounting for about 15 percent nationally, according to data from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System. That number is about 10 percent annually in Philadelphia. The remaining 85 to 90 percent of child removal cases occur for a wide variety of reasons. Many of them stem from circumstances that can be attributed to economic hardship.

Lamb herself made a journey from being investigated as a potential abuser to having her kids kept from her for some other reason. The whole situation felt so unjust, she was struck by a thought too compelling to ignore. Feeling some trepidation about how her next move may be perceived, she actually called the police to ask if DHS’s actions were legal. “I wondered,” she says, “if this was just [a] kidnapping.”

Stay tuned for Part Two, “Can Racial Bias Be Corrected in the Child Welfare System?”

Author Steve Volk is an investigative solutions reporter with Resolve Philly, a nonprofit journalism organization committed to collaboration, equity, and community voices and solutions. His work has appeared in Philadelphia, Discover and the Washington Post Sunday magazine.

Illustrator Dylan B. Caleho, also lives in Philadelphia, and is also comic artist.”I make art to tell stories, and to spark conversation,” says Caleho. “I want my art to be explained through the images only, and for the words to come secondary. If I’m able to tell the narrative without words then I’m doing my job right. You can find examples of additional work by the talented Caleho here on Instagram.