A new study of race and school discipline in California counties has revealed that the black male student suspension rate decreased 5 percent between the 2011-2012 and 2016-2017 school years—from 17.8 percent of all black boys to 12.8 percent. Racial disparities remain intact, however.

Black boys’ 12.8 percent suspension rate during the last school year was more than 3.5 times the rate of the CA public school population as a whole (3.6 percent), according to the report, which was created in collaboration between the Community College Equity Assessment Lab (CCEAL) at San Diego State University and the UCLA Black Male Institute.

Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Riverside, Sacramento, and San Bernardino, all large, urban counties, accounted for the largest suspension numbers among California’s 58 counties. Between them, they handed down a total of 61 percent of black male suspensions. Rural counties with smaller enrollment numbers for black boys, in comparison, were responsible for the highest suspension rates among their black male students. Over the last five years, San Joaquin County has been responsible for black male suspension rates of 20 percent or higher. Last year Glenn County suspended 42.9 percent of its black male students. Suspension rates in rural counties often fluctuate year-to-year, however, because they have smaller populations of enrolled students, according to the report.

A total of 10 individual school districts across California had suspension rates of over 30 percent last year. The highest suspension rates were seen at Bayshore Elementary in San Mateo County (50 percent), Oroville Union High in Butte County (45.2 percent) and the California School for the Deaf-Fremont in Alameda County (43.8 percent).

The study also showed that black boys in foster care were suspended at more than twice the rate of black male students who were not in foster care.

More than 27 percent of black boys involved with the foster care system were suspended during the 2016-2017 school year. In comparison, 15.1 percent of the general population of foster youth in CA schools received suspensions, according to the report.

Schools suspended an incredible 41 percent of black boys in foster care in 7th and 8th grade, according to the study.

The researchers call on schools to adopt regulations that only allow students in foster care to be suspended when an advocate is present. “This advocate should be the student’s social worker or another independent representative of the student’s choosing,” the report states.

Additionally, 16.2 percent of homeless black boys were suspended, compared with 5.8 percent of the total homeless student population.

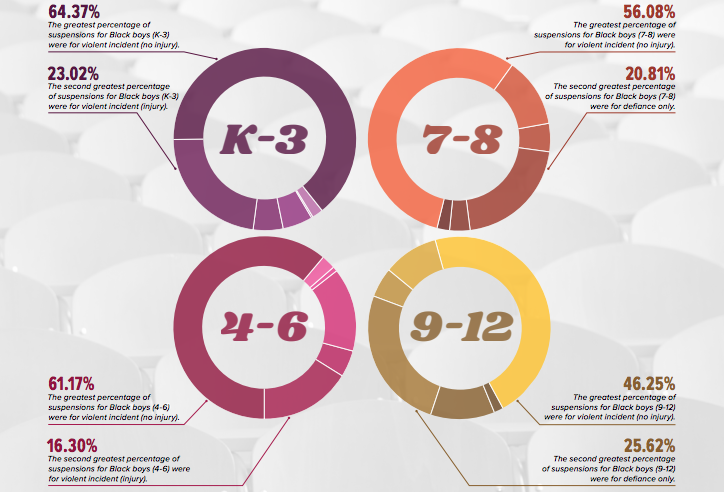

Black male students between kindergarten and third grade were 5.6 times more likely to be suspended than the state average.

The report recommends that schools work to eradicate suspension in early education, “which can foster antipathy towards school environments, negative dispositions regarding students’ perceived sense of belonging in learning environments, confidence in their academic abilities, and perceptions of the utility of school,” according to the researchers. “Moreover, these practices can also serve to erode students’ relationships with educators, a pattern that can worsen throughout their educational trajectories.” The report recommends schools replace suspensions with in-school strategies like counseling-based intervention.

Black boys were also 3.3 times more likely than other students to be suspended only for willful defiance—a catch-all category that allows schools to suspend kids for minor misbehaviors like talking back and dress code violations.

“From a very young age, far too many black boys and young men are being told, in effect, to get out, and are excluded from the school and classroom, says Professor Tyrone Howard, the director of the Black Male Institute at UCLA. It’s an unfair practice with serious consequences for learning and achievement and future success, and it needs to stop.”

There are two different types of suspension—in-school and out-of-school suspensions, the latter of which are generally used for more severe infractions. When school administrators give a student an in-school suspension, the child remains on school grounds, spending the suspension outside of the classroom (in the principal’s office or the library, for example). During an out-of-school suspension, a kid must leave the school grounds. Kids either go home or spend the suspension in a pre-determined off-campus facility.

The report recommends that the state create an exclusionary discipline taskforce to bring accountability for counties and districts identified in the report that have disproportionately high suspension rates. “As an example, this could include districts where more than 500 suspensions of black males occur in a given year, or counties where suspension rates are 30 percent or above,” the report states. The task force should “work collaboratively with these locales to establish goals, benchmarks, and interventions to reduce exclusionary discipline patterns” as well as provide training and monitoring.

“This analysis makes clear that black boys and young men are significantly over represented in exclusionary discipline practices in California’s schools,” says Luke Wood (Professor, SDSU). They are unfairly singled out for punishment, and receive harsher punishment, placing them at greater risk of dropping out, making them less likely to attend college, and opening the door to pathways into the criminal justice system.”

The researchers also recommended municipalities prepare school staff to identify and properly respond to trauma. “One of the more misunderstood aspects of student behavior is the salience of trauma,” the report states. “For many students who have been exposed to toxic stress and traumatic events, certain types of behavior are misguided pleas for help and intervention.”

Alienating these students is not the answer, according to the study. Instead, teachers and other staff must be equipped with strategies to diffuse and redirect situations, and empathize with students in distress.

“The fact that Black male foster and homeless youth have high levels of suspensions

may speak to the general ignorance or lack of support that school personnel have about mental health, trauma, and toxic stress,” the report says. “Districts need to significantly increase the number of psychiatric social workers and mental health therapists at schools to support some of the most vulnerable students.”