For more than a decade, the nation’s juvenile justice systems have steadily cut back on unnecessary use of incarceration for young people. The reduction in the use of youth lock-ups have been good for kids and for public safety. Reforms that resulted in incarcerating fewer kids, statistically improve the chances of success for youth when they become adults, while also corresponding with the steady decline in juvenile crime during the same period.

Yet, according to an important new report released by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, titled “Transforming Juvenile Probation: A Vision for Getting It Right, while there has a large reduction in the use of youth confinement, there has not been a corresponding downturn in the use of the justice system’s primary alternative to youth lock-ups, namely the juvenile probation system.

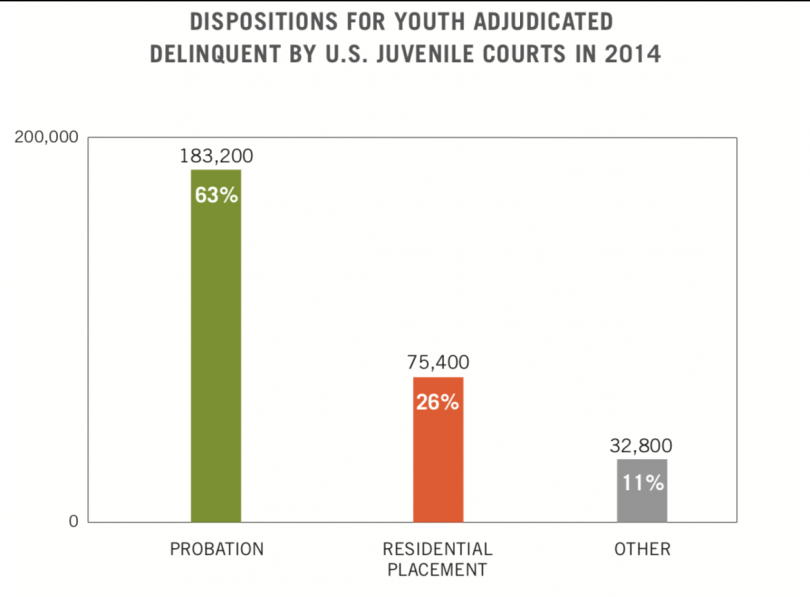

Annually, a half-million U.S. youth are given some form of probation, instead of being placed in locked facilities, according to Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention statistics. This means that a great deal is expected of county juvenile probation systems as the primary alternative to lock-up for lawbreaking youth. These expectations—from judges, prosecutors and the public—are both “unrealistic” and “conflicting” according to the new report.

Moreover, changes to the system are particularly needed, writes the report’s author, when it comes to the most challenging kids whose behavior can be a threat to public safety.

Fuzzy goals and big caseloads

In 2014, the most recent year for which juvenile court data are available, 63 percent of youth found “delinquent” in juvenile courts were sentenced to probation.

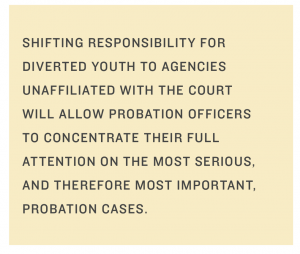

This often meant that probation officers were—and still are—struggling with “overwhelming caseloads,” which include many young people “who should not be the court’s responsibility,” states the Casey Foundation report.

To put it another way, these often bloated caseloads include large numbers of youths whose behavioral problems are rooted in abuse and neglect, trauma, mental health and substance abuse issues and/or family crises. These are kids, according to research cited in the report, “who would be better served by human services systems that are more appropriately situated to address these difficulties.”

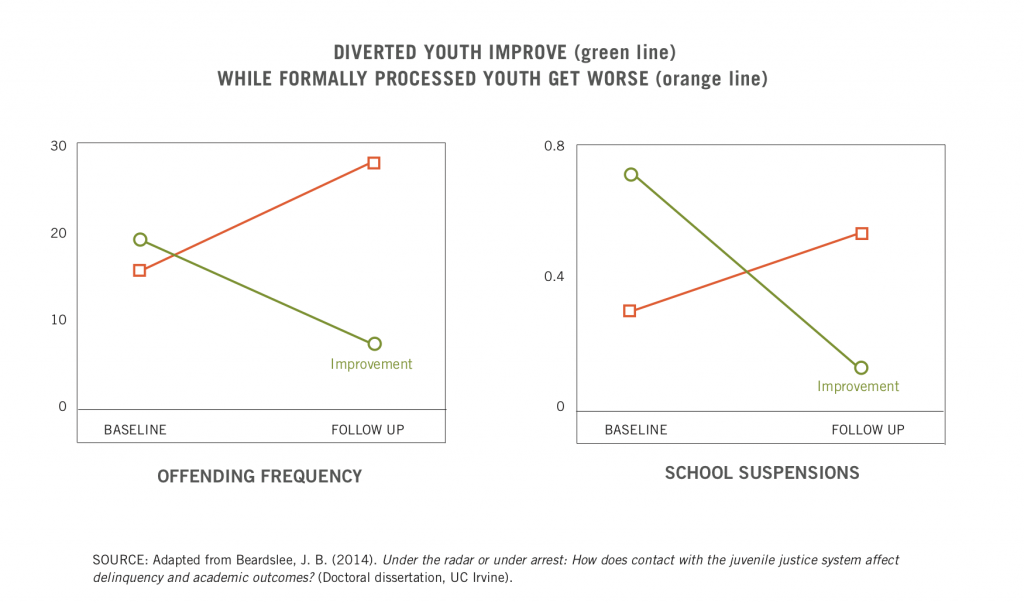

In other words, they would be better served by being diverted to non-court involved programs.

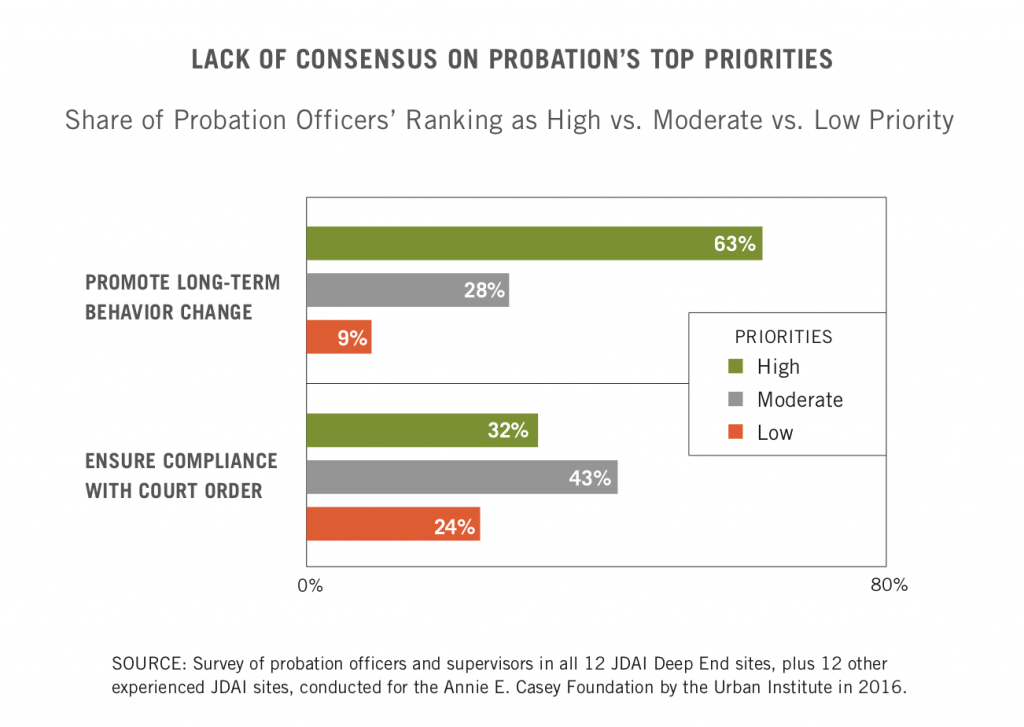

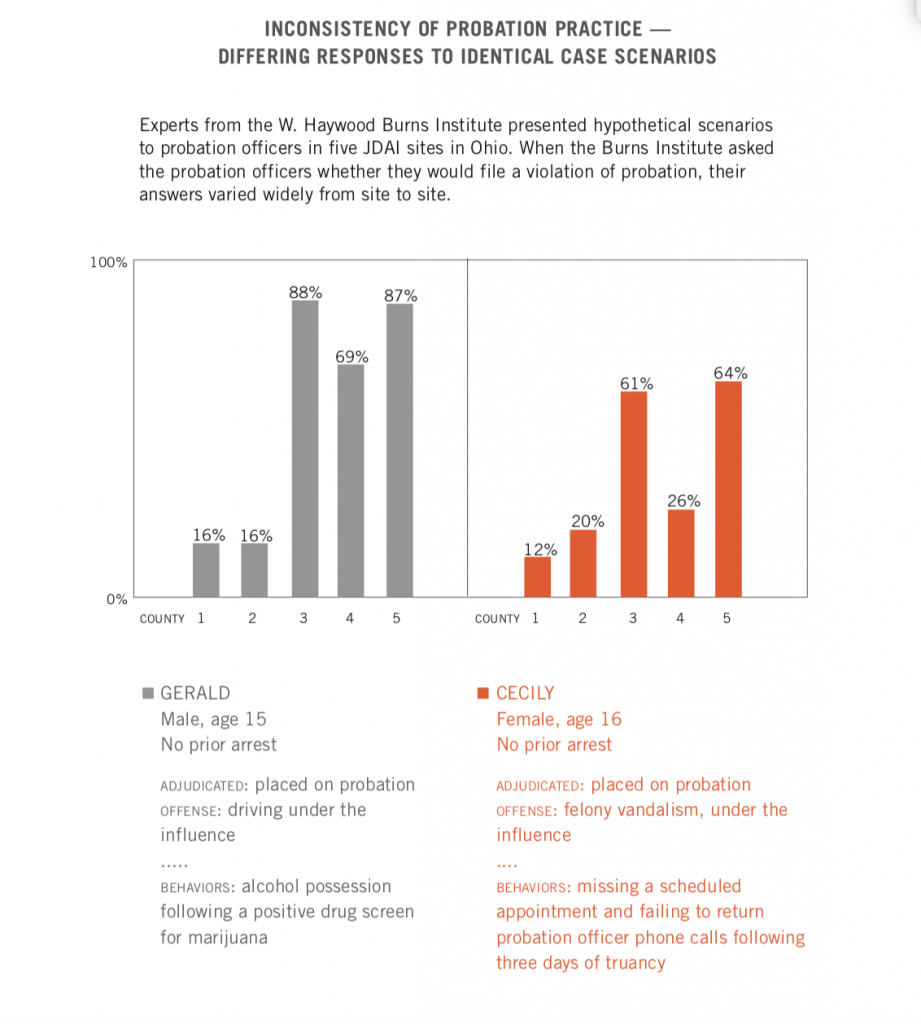

Another problem facing often overburdened juvenile probation officers is the fact many of the nation’s juvenile probation systems that employ them lack “clarity about [the individual system’s] goals and purpose.”

The result is that, “despite the dedication and admirable intentions” of probation professionals, too often probation runs the risk of unproductively pulling young people deeper into the system without offering the support and guidance that “would put them on the right path and reduce the likelihood of reoffending,” according to the report.

When it works well, probation offers court-involved youth the chance to remain in their communities where they are given the opportunity to participate in constructive and therapeutic activities.

But too often, probation can also become “a gateway to unnecessary confinement.” This is particularly true for rebellious kids who frustrate authorities with “noncompliant behavior,” but who also pose a “minimal risk to public safety.”

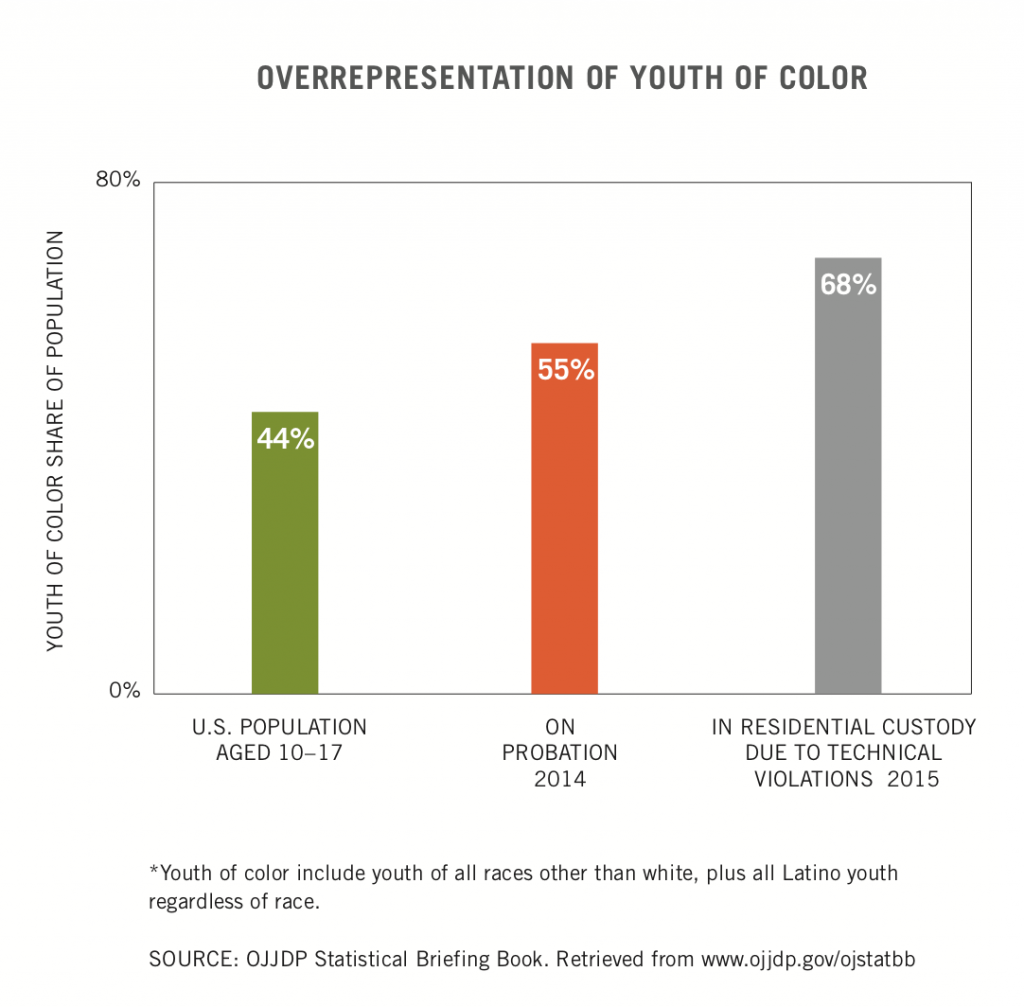

This “gateway to confinement” factor, not surprisingly, disproportionately affects youth of color and exacerbates “the already severe racial and ethnic disparities plaguing juvenile justice.”

But it doesn’t have to be that way, according to the Casey Foundation report.

Carrots work better than sticks

One of main changes that the Casey report recommends when it comes to redesigning the nation’s juvenile probation systems, is to utilize the growing body of research about what works.

For example, programs and methods designed to help kids develop abilities to mature their decision making capabilities, such as methods involving “cognitive behavioral approaches designed to improve problem solving, perspective taking and self-control,” have been repeatedly shown to reduce recidivism rates.

Whereas, interventions geared toward “deterrence, discipline or surveillance,” notes the report’s author, have been found to have “no effect,” or worse, they actually increase recidivism.

To put it another way, both youth and adults on probation have been found to respond much better—statistically—to rewards and incentives for positive behavior than to sanctions for negative behaviors.

“The use of incentives is even more important for youth,” states the report, “because it helps them learn and implement new, desired behaviors, thereby replacing—not simply inhibiting—undesired behaviors.”

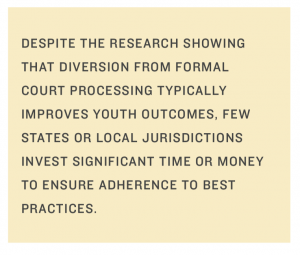

Diversion stalled

Another of the principal strategies the report highlights is that of diversion—a solution that it seems once was used frequently, but fell out of favor during the infamous “super predator” era of the late 1980’s and early to mid 1990’s.

In 1985, the report notes, 54 percent of all youth referred to juvenile courts nationwide were diverted. Of these diverted kids, 21 percent were assigned to a probation department caseload as part of their diversion agreements.

By 1998, however, the portion of youth diverted fell to 43 percent, and 26 percent of diverted youth were assigned to a probation caseload. In other words, many more youth — including many youth charged with first-time misdemeanors — were being formally processed in court and/or assigned to probation officers, even for minor lawbreaking.

Yet, despite piles of research, “the diversion rate has barely budged since 1998,” the report notes. In 2014 (again, the most recent year for which complete data are available), just 44 percent of youth referred to juvenile courts nationwide were diverted. Of these diverted youth, nearly one-fourth (24 percent) were assigned to probation caseloads, thereby helping to unnecessarily bloat the number of kids each officer was supervising.

According to the Casey Foundation report, here have been some notable regional exceptions to those numbers.

LA’s history-making move

As a signal example of a region that is taking diversion seriously, the report points to Los Angeles County.

“The nation’s larges county goes all in for juvenile division,” the report trumpets in a sidebar ( though the first stage of LA’s ambitious plan is not scheduled to open until this summer).

“On November 7, 2017, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors enacted a historic new juvenile diversion initiative, perhaps the most ambitious in our nation’s history, which will steer thousands of young people each year away from the juvenile court system and into supportive services in the community,” according to the report. “Not only will young people diverted through the program be shielded from referral and adjudication in juvenile court, most will also avoid any arrest or citation.”

The report goes on to detail the reforms, stating that “roughly 11,000 (about 80 percent) of the 13,665 arrests and citations issued to county youth in 2015 would have been eligible for diversion under the new system — including youth accused of status offenses, misdemeanors and most nonviolent felony offenses.”

The plan authorizes law enforcement officers either to “counsel and release youth they apprehend (for any status or misdemeanor offense), or to refer youth to diversion programs in lieu of arrest (or in some cases, following an arrest) for any misdemeanor and many felonies.”

The newly-created Office of Youth Diversion and Development, the report states, “will be charged with forging partnerships with the Los Angeles Police Department, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and several dozen smaller law enforcement agencies…to promote the use of diversion.”

In addition the county has “allocated $26 million to pay for an array of community-based programs and services, with the goal of securing another $14 million over four years to fully fund the planned service continuum.”

Of course most WLA readers know all this, because we reported on the historic new diversion initiative here, which we were happy to see the Casey report noted in its footnotes.)

The Tougher Cases

As important as the report finds diversion, the Casey report notes that, even if our nation’s juvenile justice systems manage to extend diversion “in all appropriate cases,” there will still be a sizable population of young people “who pose a more serious threat to community safety”

For these kids, “probation supervision is necessary to protect the public,” the report’s author writes.

“Protecting the public must remain a core purpose for probation and the juvenile court generally.”

But, for these youth in particular, according to the report, it is most crucial to use approaches that are proven to work “in reducing young people’s likelihood of rearrest.”

This means, according to the report, that probation’s guiding purpose must be “promoting personal growth, positive behavior change,” and long-term success, rather than simply “compliance,” which for too many agencies is still the goal, according to the report, whether that goal is officially stated or operates by default.

Using research backed approaches, probation can be effective tool “for helping youth with more significant offending histories to turn away from delinquency, develop self-awareness and other critical life skills and begin achieving important milestones on the pathway to success in adulthood.”

But—the report emphasizes—probation agencies can only achieve this progress if they embrace “a new and better- honed approach that emphasizes building relationships, matching interventions to youths’ needs, focusing on incentives rather than sanctions and providing opportunities for positive youth development.”

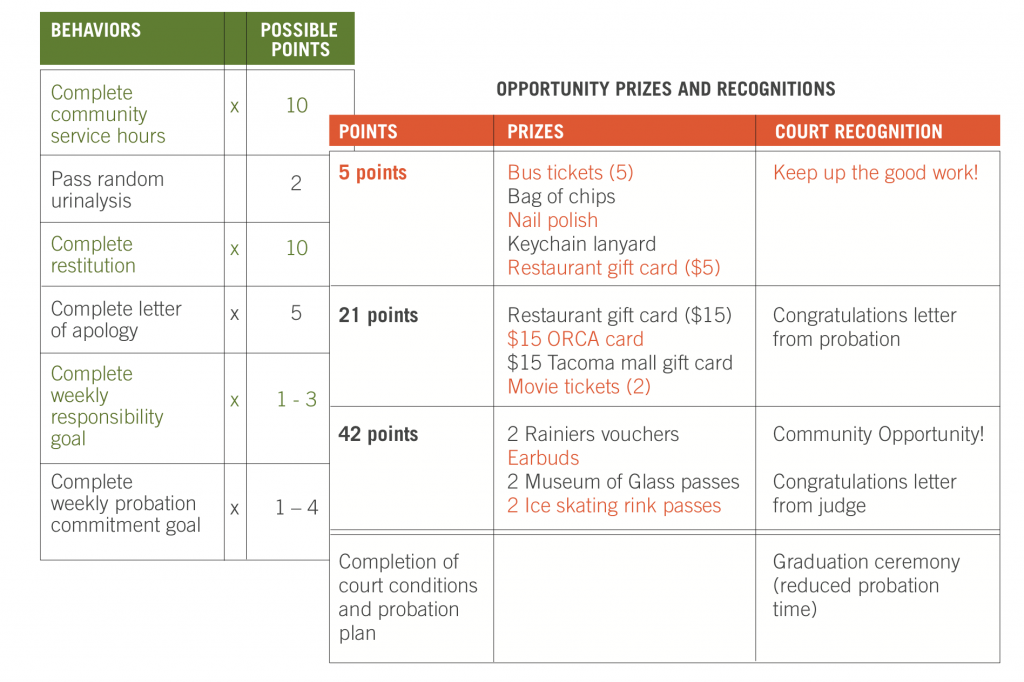

As an example of how this strategy works, the Casey report points to, among other places, Piece County, WA, which has “moved aggressively to update”

its juvenile probation practices.

“Probation has become much more than just supervision,” says Pierce Juvenile Court Administrator T.J. Bohl, in the report. “We are evolving into a more Positive Youth Justice model that promotes behavior change, skill acquisition and healthy relationships.”

The Casey Foundation writes of Pierce’s most ambitious new program, “Opportunity-Based Probation,” which was designed in partnership with a University of Washington researcher.

This approach reportedly shifted Pierce’s probation’s emphasis from “deterring misbehavior” to “incentivizing positive behavior change and personal growth.”

When kids meet weekly goals identified in their case plans, they receive points which can be redeemed for prizes (bus passes, gift cards, passes to popular venues) or for opportunities to participate in certain popular “enrichment activities.”

Similarly, when a kid breaks the rules, or fails to complete the goals he or she has agreed to, the kid may temporarily lose his or her ability to earn or redeem points or other privileges. This often also results in the requirement to participate in “a problem-solving conversation.”

But, in Pierce County, rule-breaking kids are rarely sanctioned in any legal way. “Young people are returned to court only if their problematic conduct endangers public safety.”

When a sanction is necessary

Even in cases when noncompliance rises to the level that warrants a probation violation, according to the report, the violation should trigger a review in which the judge may or may not revise the terms of the probation order.

In those instances, the Casey Report states, everyone involved in the young person’s case (youth, family, probation officer, service provider, mental health counselor, etc.) should “work collaboratively to diagnose the underlying problem(s) and brainstorm new approaches” that might be incorporated into the young person’s case plan.

Two steps forward, one step back

There is, of course, lots more to this 56-page report, which was based on five years of examining juvenile probation research, and experience with pilot “probation transformation” sites, that the Annie E. Casey Foundation has sponsored. The report’s author also got input from a list of former and present chief probation officers from all around the nation, among other experts.

In the near future, the Annie E. Casey Foundation will follow up on this report with the publication of “a probation transformation playbook, which they say will provide more detailed recommendations for change in probation and diversion practices.

Meanwhile, probation can only succeed if it accepts that for kids, the process of change is gradual, “often a matter of two steps forward and one step back.”

All charts and other graphics courtesy of The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s May 2018 report, Transforming Juvenile Probation: A Vision for Getting it Right.

Again, Celeste, the information provided categorizes the kids into a general pool of fully equipped and ready to respond adolescents. Why doesn’t Witnessla form a program to be implemented in any of the halls and attempt to prove what it so passionately desires. Grab your best writers and friends and venture down to the halls to build these healthier relationships. You and I know that all the thousands of dollars is required to change a child’s life in the very early stages of deviance and instability. Probation receives these youth in already critical phases of change. There are no articles that create the key successes of life for an at risk youth. You have to be there in their face having discussions, breaking down the challenges, and sharing in their despair which often is seen in their tears of unexplainable frustrations. Your heart is in a great place as it is for most all of the stakeholders involved. I am sure that instead of the constant reporting of failures that seems to revolve in your report writing; you also learn to strengthen those who need your support as well. This probation system is not a project for those who are at the decision making table with a bank roll and political ties. You have unfairly hurt others with your articles and have no clue in doing so. Your criticisms are well noted. Thank you.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Dear “from a distance,”

Thank you for your very eloquent and informed critique. As we struggle daily, weekly, and monthly to choose where to put our efforts and time, voices like yours are extremely helpful—even though often it may not seem like we’re listening well enough as you read our coverage.

Gratefully yours,

Celeste

Bravo Up & Personal, your comments are on point…thank you!!!

From: Up Close & Personal

Correction

Bravo From a Distant, your comments are on point…thank you!!!