EDITOR’S NOTE: This is Part Two of a two-part series in the “Our Kids” reporting project. Our Kids is a project of the Broke in Philly reporting collaborative that examines the challenges and opportunities facing Philadelphia’s foster care system.

Part One of the series, “In the Child Welfare System, Black Families Should Matter,” looks into Philadelphia mom Kyeesha Lamb’s encounters with the child welfare system, examines the disheartening statistics, both in Philadelphia and nationally, that show how Black families are disproportionately subjected to child welfare investigations and removals, and reports on scholars and activists calling for a reimagining of the entire system.

So, why Philadelphia? While WitnessLA generally reports mostly only on issues in Los Angeles and around California, this two part series — which originally ran in NEXT CITY — skillfully points beyond itself to the destructive and disproportionate treatment that too many Black families, Indigenous families, and Latinx families all over the nation, including in California — and, yes, in Los Angeles — are experiencing when they come in contact with the child welfare system.

For these reasons we wanted to bring this important series to WitnessLA’s readers.

So read on.

How one New York county tried a solution that dramatically reduced the number of Black and white children in foster care.

Story by Steve Volk

Illustrations by Dylan B. Caleho

Earlier this year, Kyeesha Lamb called the police on Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services, thinking that their effort to take and keep her children might meet the legal definition of kidnapping.

The previous month, DHS had taken both of Lamb’s children, suspecting that one of them had been the victim of child abuse. (To read more of Lamb’s story, See Part One, “In the Child Welfare System, Black Families Should Matter.”) A second set of x-rays later revealed that a suspected broken leg was in fact not broken at all. But DHS, which had Lamb’s children already in their custody for three weeks, was determined not to return them to Lamb until a hearing could be held. The agency now alleged that she had been a victim of domestic abuse.

How can they do this? Lamb wondered. How can they take my children over one specific allegation and then, once I’m cleared, keep them over a suspicion of something else? Something they hadn’t even proven?

Lamb had called the police with trepidation, unsure of how the call would be received. The officer she reached was polite, if unhelpful.

“You’ll just have to go through the child welfare agency’s process,” the officer said.

Lamb hung up, despondent. What felt to her like child abduction, is often how the child welfare system operates.

She wondered how this could happen to her; she thought that her race might be playing a part. In the wake of last summer’s marches demanding racial justice, she wasn’t alone in seeing the role that bias plays in various facets of American life. Scholars and activists are noting the insidious forms that systemic racism takes, as well as the short- and long-term trauma that investigations and removals cause children and families across the child welfare system. Two county agencies, in New York and Michigan, have tried new approaches to correct for the disproportionate presence of Black and Brown families in the system. The results show promise, even as they raise questions about what more can be done.

For low-income Americans, a long history of Child Removal

Not far from Lamb’s house, Marcía Hopkins had watched the protests of police violence unfold with a sense of recognition. Hopkins, a social worker and senior manager with the nonprofit Juvenile Law Center, is one of many child welfare reformers and abolitionists who view police murders of people such as George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and the workings of the modern child welfare system, as arising from the same historical and modern-day forces.

“We know that there is a huge racial component of the child welfare system and policing,” says Hopkins. “And I think people intentionally forget the history.”

Historically, the modern-day police force originated in the American South, from racist roots. Patrols that organized to find and recapture escaped slaves evolved to take on additional responsibilities. The child welfare system was born from similar original sins. “Orphan trains” operated for 50 years until about 1929, transporting children from economically struggling families — many of whom still had living parents — to wealthier homes, where they often worked as servants, or out West, where they worked on settler farms. In the post-slavery period, Black youth were often sent North, away from their families, to accepting white families to live as indentured servants; they were referred to as “freedom’s children.”

Historian Mary Niall Mitchell writes, “The irony of sending former slave children hundreds of miles away to fill the needs of northern employers for dishwashers and household servants … seems to have escaped some of their sponsors almost entirely.”

Even today, Hopkins points out, local agencies can tap greater federal resources to compensate for the costs of caring for children if those kids come from economically struggling families. The federal government also offers greater financial aid for states to separate families and put kids in foster care than it does to fund programs that keep families together, creating a pair of perverse incentives for cash-strapped states to focus on families experiencing economic distress and to opt for separations.

While law enforcement and foster care do appear to have unfolded in this country on parallel tracks, critics suggest that the child welfare system might actually hold more power, investigating and punishing not just crime but family behavior. Clearly, this is what Lamb faced as issues such as co-sleeping became a point of judgment. In this respect, University of Pennsylvania family law scholar Dorothy Roberts has noted, child social workers act as an intrusive arm of law enforcement.

Child Protective Services needs only a tip from the public, even an anonymous one, to knock on a family’s door. “We have received a report that your child(ren) is a victim of abuse and neglect,” they might say. “Will you open the door so I can come in and investigate?”

If the response is “no,” they will warn that their next step is to come back with a police escort — a rapid escalation that carries an implicit warning: This allegation against you appears more credible if you deny us entry.

If caseworkers arrive at night, as they often do, and the allegations reference physical abuse, they can tell parents to wake up their children. Sleepy-eyed, confused, the kids might then be asked to remove their clothes for a stranger — a strip search without a warrant — so they can be inspected for signs of bruises or other injuries. Some reasonable people might want social workers to hold this kind of power, to prevent kids from being hurt. But at this stage, even if no sign of abuse is found, or if the complaint was about child neglect, the worker can indicate they need to inspect the home.

The caseworker takes inventory of the amount of food, and how healthy it is. (Why no milk?) Notes the leaks, broken windows, rickety banisters and general quality of housekeeping. Are the kitchen counters clean? The ceilings and floors? Like housing inspectors, they turn on faucets and ovens to see if they work. In winter and summer, they note the temperature, to make sure the house is safe and comfortable. If a parent admits they just smoked a blunt (Do you have a drug problem?) or reacts to the surprise intrusion and interrogation with anger (Do you have an anger problem?), the caseworker might count this against them. And as the visit ends, the worker can, at their discretion, seek an emergency court order to take the children on the spot.

The “Family Regulation” system

Some child welfare scholars, including Roberts and writer Emma Peyton Williams, look at the power caseworkers wield and argue that the “child welfare system” should be renamed. The suggested alternative, the “Family Regulation System,” they argue, is more accurate and reflects statistics that show time spent in foster care often yields not “child welfare” but long-term suffering — including high rates of trauma, adult homelessness and poverty, and mental and physical health issues related to stress. Family regulation also represents the full range of what caseworkers do — not simply (and not overwhelmingly) abuse investigations, but whether families under scrutiny meet societal standards for housing, nutrition and supervision.

“It’s a system in which families are being held up against a white middle-class standard of how families are supposed to operate,” says Peyton Williams, “and it’s Black families that are disproportionately reported to this system and held up to this standard,” even when white families engage in the same behaviors.

In Philadelphia, practicing family law attorneys — who asked to speak anonymously for fear of backlash from DHS or the court system — acknowledge seeing questionable child removals on a regular basis. Factors directly related to economic hardship, such as transience — moving from house to house — or the nebulously defined “poor judgment” are sometimes given as reasons for removal. (One family attorney says that a family was separated because a caseworker felt no child could be safe living in a rooming house.) And parents who leave children, ages 7 to 9 or older, home alone for a few hours for work or in an emergency can be charged with “abandonment.”

City council hearings to evaluate DHS practices often include multiple mothers who appear during the public comments section to decry the agency’s behavior. One woman, Yolanda Bryant, who spoke at multiple meetings, says that reporting potential abuse done to her grandchildren has led to a nightmare in which she lost access to three grandkids, including one who had been in her custody since birth. “I have not even been able to get into hearings to argue for myself,” she says. Stories such as this one, and Lamb’s, are tremendously difficult for the media to vet and publish because case records and court proceedings are closed, theoretically allowing for families to make baseless allegations or for dysfunction and bias in the system to persist.

Just this February, a panel of family law experts, including Roberts and a Community Legal Services managing attorney, Kathleen Creamer, appeared on a Penn Law virtual symposium panel dubbed “Family Surveillance: A Future Without Foster Care,” where they discussed obvious double standards around issues such as drug use. Black parents caught up in child welfare investigations routinely have recreational marijuana use cited as a mark against them. Yet, states around the country — most recently New York and New Mexico — are routinely legalizing pot. A decade ago, tony Philadelphia magazine celebrated white soccer moms who smoke weed.

In addition to arguing for a systemic name change, scholars such as Roberts and Peyton Williams argue that this kind of racism and hypocrisy is sewn so deeply into the system that we should dismantle it entirely and start over — a criticism that echoes calls to abolish (not merely defund) the police.

But there have also been attempts to address the problem. One approach in particular has shown some success, even as it reveals just how deeply the problem of race is rooted.

The problem of “blind removal” meetings

About a decade ago, Maria Lauria, then the director of children’s services in Nassau County, New York, thought she saw a problem in the office. “I was there [for] about 20 years and I noted what I thought was some bias,” she says. “I would not say it was overt, but it concerned me.”

The numbers bear her out. In 2010, though Nassau County was about 13 percent Black, Black children represented 55 percent of the youth in foster care. Dismayed, Lauria focused on the system’s most crucial decision point — the choice to break up a family.

Typically, caseworkers who decide to move ahead with child removals show their findings to supervisors for approval. Lauria suggested these meetings should include less information — eliminating names, addresses, zip codes, anything that might indicate a family’s race during presentations. Her bosses liked the idea, but her initial presentation to co-workers didn’t go so well.

“People hated it,” says Lauria. Some affronted colleagues declared, “You’re calling us racist.”

In response, Lauria’s department instituted training on “implicit bias,” a set of stereotypes about race and class that are spontaneously and unconsciously activated, potentially causing white people to treat Black and other nonwhite people differently. Unconscious bias is a regular subject during diversity training in modern workplaces, though some research finds such training can increase discord — causing whites to feel angry at being called “racist,” and fearful of being discriminated against.

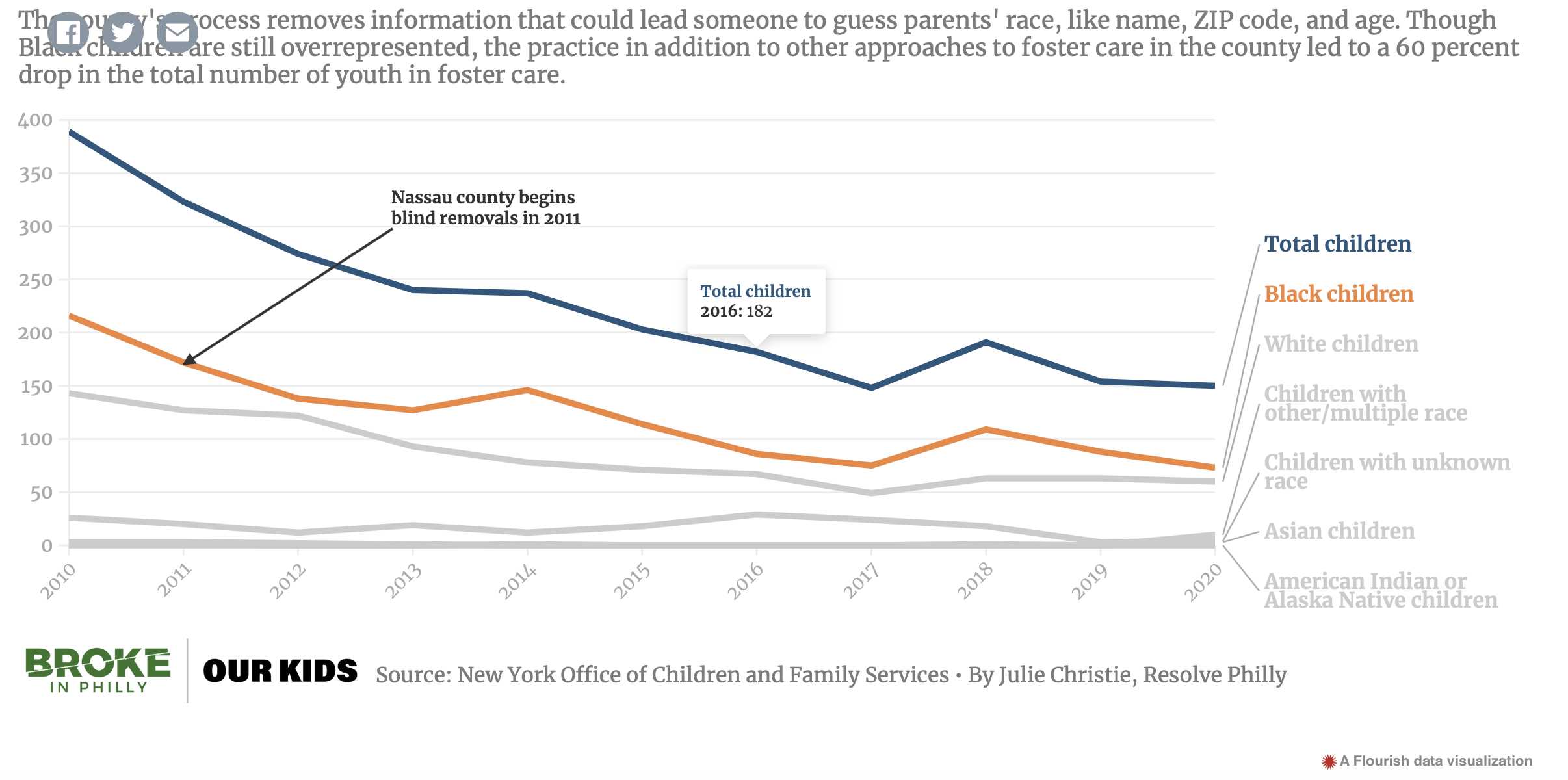

Despite the resistance, Lauria’s system was implemented by 2011, beginning a five-year period in which the number of Black youth in foster care declined by 60 percent.

“It was beyond anything I’d imagined,” says Lauria. “It was so successful.”

Director of The Florida Institute for Child Welfare Jessica Pryce published a case study about the program, which led to a May 2018 Ted Talk that has been viewed 1.3 million times. Lauria emerged as a hot property among conference speakers, won a prestigious Social Worker of the Year Award and got promoted to Social Services Program Coordinator. Blind removal meetings were by far the most significant policy change in Nassau, suggesting they are the main driver of the reductions, but the concept remains deeply controversial.

“People do not react well to it,” says Lauria, of her conference presentations. “It’s the same stuff I got before: ‘Are you calling us racist?’”

The program also isn’t expanding as fast as might be expected. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an administrative order in October 2020 calling for blind removals to be implemented statewide. But only one county outside New York, in Michigan, has implemented its own pilot program.

On one hand, such resistance might appear surprising. Calls to reduce disproportionality and the total number of kids in foster care, across races, are commonplace. Casey Family Programs, which works in all 50 states with a mission to improve child and family well-being, has called for a 50-percent reduction of youth in foster care. Agency leaders around the country, including in Philadelphia, talk about “right-sizing” their systems.

After implementing blind removals, the number of Black children in foster care dropped in Nassau County

Ten years after the Nassau experiment began, their numbers reflect a measure of success different from what its creators had targeted. But those numbers suggest that blind removal meetings do offer some help. Disproportionality remains, but has lessened — Black kids still represent 48 percent of the foster care population. And there have been fluctuations in the model’s performance. The county underwent an unexpected spike in the number of Black youth brought into foster care in 2018, for instance, before the next year brought a sharp decline. These results offer a reason for skepticism around a program still in its infancy.

Still, in 2019, the total population of youth in Nassau County’s foster care system, regardless of race, had declined by 60 percent. While Black youth saw the most significant reduction (60 percent), the number of white kids plummeted almost as much (56 percent). In another telling stat, the number of new, first-time entries into care fell by similar proportions. Kent County, the Michigan county conducting a blind removal pilot, reports a similar result, with the total number of youth taken into foster care, regardless of race, declining by about 50 percent.

The reductions in both Nassau and Kent counties coincided with the introduction of blind removal meetings. How could this be? Lauria’s old boss, Karen Garber, says blind meetings held unanticipated effects.

“We were not ordering as many removals,” says Garber, who retired from Nassau County in December 2019, “so we were thinking more creatively. We were asking ‘what does this family need?’ and ‘what can we do for them?’ We were in a different mindset.”

The blind removal process also helps to reduce the effect of other biases a caseworker may bear, she adds, related to a particular family’s generational history, or a specific zip code or address, regardless of race.

Lauria declines to speculate on why the numbers of Black youth being taken into the system spiked, or why disproportionality has not lessened more dramatically, vowing to keep “investigating” the program. But by definition, changes in how removal meetings are conducted don’t render the entire system race-blind. Front-line caseworkers and mandated reporters meet families in person, perceiving their race first hand. And systemic issues around economic hardship aren’t addressed at all — a limitation in a system that encounters “neglect” more often than actual abuse.

Philadelphia DHS’s ongoing disproportionality study so far echoes Nassau’s experience, revealing a strong correlation between a family’s generational history of involvement in the child welfare system and current foster care placements. The study also yielded a stark mapping visualization of how census tracts with high concentrations of economic hardship and a large population of Black residents have a higher rate of families referred for investigations.

“Neighborhoods with the most reports to DHS were also those same historically Black neighborhoods that were redlined and subsequently have experienced residential segregation, disinvestment and resource deprivation, and over-surveillance by police and child welfare systems,” the research brief reads.

Authors of the study recommend, among other measures, increased implicit bias training and the ambitious goal of “city-wide poverty alleviation,” noting with candor that “the high number of DHS reports related to neglect suggests that many of the families come to the attention of DHS because of poverty.”

Against this painful historical backdrop and in light of persistent challenges, blind removal meetings won’t fix the system wholesale. But the steep drop in the number of kids entering foster care in the two counties that employ this practice suggests they could comprise part of the solution.

“I’m not opposed to blind removal meetings,” says Miles Cloud, at Movement for Family Power. “From all the numbers I’ve seen, they seem to make a significant effect on disproportionality. But they are a singular intervention, in an entire ecosystem that needs to change.”

For Lamb, exoneration brings no resolution

One day early this February, Kyeesha Lamb received an important letter from DHS. “The agency has investigated the report,” against her, the letter read, “and determined it was unfounded.”

By now, she already knew that the agency intended to keep her kids until the next hearing. Twelve days later, when the hearing date finally arrived, she expected the agency would simply give her kids back. Instead, her attorney notified her that the agency intended to seek “adjudication,” a ruling from the judge mandating that the family remain under DHS’s supervision.

“I told them I wasn’t in agreement with the adjudication,” writes Lamb’s lawyer, in a text. “They are saying they may continue the hearing to another date. … I don’t think they have a basis to adjudicate but it’s up to you if you want to agree to the adjudication & get the kids back home today. Let me know.”

By this point, Lamb had endured three weeks since the x-rays came back in her favor, and around six weeks total, without her kids. Now she felt she was being threatened with an additional delay.

She wrote back to Cochran, saying yes to the adjudication but feeling coerced. A caseworker, she learned, had claimed that Lamb admitted there had been domestic abuse in the past, but Lamb says she was asked and denied it. She also produced emails she sent to the caseworker’s supervisors, complaining about “false statements.”

Later that day, because of COVID-19 restrictions, she called in to the hearing via telephone. She denied any allegations of trouble between her and her boyfriend, she says, or that the baby’s accident happened while they fought. The judge, in turn, ruled that she could get her kids back — a decision Lamb greeted with gratitude and relief — but also granted DHS’s request to maintain authority over her family.

I’m not opposed to blind removal meetings. From all the numbers I’ve seen, they seem to make a significant effect on disproportionality. But they are a singular intervention, in an entire ecosystem that needs to change.

After the proceeding, Lamb received a copy of the judge’s order that disturbed her. “The court finds that clear and convincing evidence exists to substantiate the allegations set forth in the petition,” the order reads.

The only petition, or list of allegations, Lamb ever received, however, focused on the potential child abuse that hospital x-rays later ruled out, and notes the delay between the child’s injury and the hospital trip.

This disconnect between what DHS originally alleged in writing and the argument they ended up making in court looms as somewhat typical of a dependency court system that operates by different customs than other courts.

During her February hearing, Lamb says, a DHS caseworker testified about the relative who alleged a domestic argument — testimony that is inadmissible hearsay but often slides through in dependency court. Lamb’s attorney objected to the testimony, but longtime observers of the court system in Philly and outside Pennsylvania say this sort of occurrence — in which the people making accusations are not even called as witnesses — is common in dependency courts around the country. To critics, this dynamic exemplifies systemic racism, treating the separation of families — mostly Black and almost always economically struggling, regardless of race — as lacking enough importance to require a full hearing. Now Lamb is experiencing this system up close. And DHS’s continued authority over her is significant.

She will need to take parenting classes, attend personal therapy sessions and accept regular visits from caseworkers. Anything DHS deems a slip-up could put her back in the same position, without her kids. And she also needs to deal with the psychological ramifications — for herself, her boyfriend and children, of such a profound disruption in their lives.

Last year, an investigative story published by the Marshall Project found that so-called “short stays” in the foster system such as the “kidnapping” that Lamb describes produce lifelong traumatic effects, according to experts and studies on child development. At this point, Lamb expresses some additional relief, saying her kids have been extra affectionate since returning home. But this could also be a sign of trauma.

“It’s hard to generalize about separations,” says Allyson Mackey, a UPenn assistant professor of psychology and expert in childhood brain development, “because it matters what environment the child was being taken away from. What is generalizable is that an extended separation, more than just [during] the hours a parent might be at work, has an effect on family bonding,” which is important for all babies and children.

People might also think an earlier trauma is better because the child will forget it. But Mackey says no. “It might actually go the other way,” she says, “because a younger child’s brain is even more sensitive to early life stress.”

The affection that Lamb’s children showed her, after their return, “could be thought of as a sign of anxiety,” says Mackey — the babies grabbing on tighter to the parents they didn’t want to be separated from in the first place.

Lamb, looking back at what has transpired so far, displays gratitude toward the judge who sent her kids back home, and upset with the system as a whole.

“I just feel … I hate to say the word, but I feel like they’re treating me like some dumb ‘n,’” she says. “Like I can’t read and I don’t know what any of this means. But I can, and I do.”

Lamb’s voice broke a little as she shared this (she herself only used the letter ‘n’). But the tone she strikes is defiant, a declaration of individual determination in the face of a system that she feels to be dragging her down, at least in part, because of her race. “I got this,” she said, at one point. “Because I’m gonna do what I need to do and keep my kids. But that doesn’t make what they’re doing right.”

Author Steve Volk is an investigative solutions reporter with Resolve Philly, a nonprofit journalism organization committed to collaboration, equity, and community voices and solutions. His work has appeared in Philadelphia, Discover and the Washington Post Sunday magazine.

Illustrator Dylan B. Caleho, also lives in Philadelphia, and is also comic artist.”I make art to tell stories, and to spark conversation,” says Caleho. “I want my art to be explained through the images only, and for the words to come secondary. If I’m able to tell the narrative without words then I’m doing my job right. You can find examples of additional work by the talented Caleho here on Instagram.