While the number of California kids arrested for felonies dropped 55% between 2003 and 2014, the number of kids transferred to adult court (directly filed by prosecutors) rose 23% during the same years, according to a collaborative report from the W. Haywood Burns Institute, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, and the National Center for Youth Law. The data suggests that there’s no discernible relationship between direct files and and youth felony crime rates. During the same decade, the number of judicial transfer hearings (where judges decide whether to send kids to adult court) dropped 69%. At the same time, more kids are being held in lock-ups during their trials, rather than being released, despite the drip in transfer hearings.

Today in California, there are three ways kids can be prosecuted in the adult justice system. In the first, a judicial transfer hearing, a judge considers the case particulars, including the kid’s background and other circumstances, and adheres to a set of criteria to decide whether the youth is “fit” for the juvenile system. Among these criteria are the severity of the offense, any prior involvement with the justice system and previous attempts at rehabilitation, and the juvenile’s level of “criminal sophistication.” A judge usually takes about six months to make a decision.

In a direct file decision, a prosecutor usually has 48 hours to decide whether to file charges against a kid in adult court, without all of the background information reviewed during a judicial transfer hearing. The direct file to adult court becomes mandatory if the prosecutor says the child committed a crime that, if committed by an adult, would carry a death penalty or life-without-parole sentence. And in discretionary direct file cases, if the prosecutor says the kid committed a “qualifying felony”—define—then the prosecutor is given discretion to either file charges against the youth in juvenile or adult court.

Proposition 21, a 2000 voter-approved law called the Gang Violence and Juvenile Crime Prevention Act, gave prosecutors far more power to charge kids as adults. Thanks to Prop 21, prosecutors have been able to bypass judges’ hearings, and directly file charges against kids as young as 14. The law also greatly expanded the qualifying offenses that trigger direct files.

Direct files are harmful to kids for a number of reasons. Prosecutors overuse the tool, disproportionately directly file black and Latino kids, and send kids into an adult system not prepared to meet their unique needs (emotional needs, education needs, safety needs, and so on).

Last Monday, the California Supreme Court ruled in favor of allowing Governor Jerry Brown to bring his proposed criminal justice reform ballot measure before voters in November. The measure would block direct files, giving judges, rather than prosecutors, the final say on whether juvenile offenders are charged as adults (in addition to other reforms, like increasing prisoners’ access to good time credits). The Supremes reversed a ruling by a superior court judge who sided with a California District Attorney’s Association members’ lawsuit alleging that amendments to the initiative did not go through the proper legal process.

A CLOSER LOOK AT THE NUMBERS

The report compares data from California’s 58 counties and how they use (or don’t use) direct file.

Not counting two counties that had five or fewer transfers to adult court in 2014, Los Angeles had the lowest rate of direct files—24% (18 cases), compared with 76% (57) via a judge’s transfer hearing. Merced and Riverside Counties have the second and third lowest direct file rates at 29% and 42%, respectively. Overall, in the state of California 72% of transfers to adult court (474 cases) were via direct files; 28% (183) were via transfer hearings. In 14 counties—including Ventura, San Diego, Sacramento, San Joaquin, Contra Costa, and Tulare—every time a kid was charged as an adult, it was through a direct file. San Francisco and 24 other (far less populated) counties reported no direct file or transfer hearings during 2014.

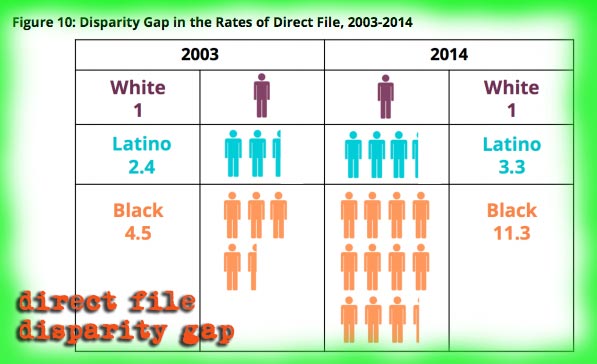

And while the direct file rate has decreased for white kids, it has increased for youth of color. In 2003, Latino juveniles were 2.4 times more likely than their white peers to be directly filed. By 2014, that number increased to 3.3 times more likely. For black kids the direct file rate jumped from 4.5 times more likely than their white peers in 2003, to 11.3 times more likely.

CALIFORNIA LAWMAKERS DEBATE WHETHER TO INCREASE TRANSPARENCY IN NEAR-FATAL CHILD ABUSE CASES

Last month, state lawmakers shot down a “trailer bill” attached to the California May budget revision, which would have closed off public access to records regarding abuse-related near-deaths of children involved in the child welfare system. (Lawmakers dumped a similar trailer bill last year.) Current state law does not require reporting in these cases, but also does not ban it.

According to the California Department of Social Services, over the past eight years, there were 855 CA kids so severely beaten that they nearly died (980 did die).

By way of the trailer bill, the California Department of Social Services, was trying to keep $5 million in federal funding that requires the state to clearly define what kind of information is to be released in almost-deadly child welfare cases. Mitchell and fellow lawmakers believe the department’s solution—which includes providing shortened summaries of the cases, without original case notes—is not the answer.

California Senator Holly Mitchell, who chairs the committee that blocked the sneaky trailer bill, says she believes the case information should be publicly available. “We spend a lot of time talking about the value of transparency in government, and I think that applies to this scenario, too.” Mitchell said. The goal is that more attention on the nearly fatal cases might lead to “a different internal procedure that can have a positive outcome for the next child,” Mitchell added.

A new version of the bill is currently being negotiated.

CALmatters’ Laurel Rosenahll has more on the issue. Here’s a clip:

Disclosing a summary of findings would protect the privacy of a child recovering from abuse and adults or siblings in the home who were not responsible for it, state officials said, while meeting federal reporting requirements. Their plan had support from the Service Employees International Union, which represents social workers, and the County Welfare Directors Association, which represents local agencies that oversee child protective services.

“We appreciate the Administration’s thoughtful balancing of the public’s right to know certain relevant information about these types of incidents with the need to protect privacy for the affected children who are still alive and trying to recover from serious injuries and trauma,” the groups wrote in a joint letter of support for the bill.

But Ed Howard, a lobbyist for the Children’s Advocacy Institute, protested that the administration’s approach “elevated the needs of government over the needs of kids.”Foster youth groups objected, too, arguing that original documents are more informative, and releasing them after near-fatalities would force counties to improve in how they look out for kids.

Children’s advocates and newspaper publishers lobbied for a bill that would require disclosure of reports on near-fatalities the same way it’s done when youngsters die.

The administration’s latest proposal surfaced last month as part of Brown’s revised state budget blueprint — a common way of passing laws that may be only tangentially related to the budget and one that avoids the lengthier vetting regular bills receive.“They simply thrust it on everyone with this gun-to-the-head approach and attempted to get it jammed into the budget that way,” said Jim Ewert, lobbyist for the California Newspaper Publishers Association, which promotes open government and access to public records.

EAST LA TEEN REDIRECTS HIS LIFE WITH HELP FROM LASD DEPUTY

At 12 years old, Junior Mendez led officers on a chase while under the influence. By the time he was 16 years old, the East LA teen was doing drugs, getting into trouble, and no longer going to school. LA County Sheriff’s Deputy Jerry Ambriz tried to help Junior make it through an LASD youth intervention program, but Junior quit. Not long after, in a pivotal moment, the teen decided to turn his life around, and re-enrolled in the Vital Intervention and Directional Alternatives program, taking advantage of Ambriz’s offer of mentorship and support. Now, at 17 years old, Junior is one of 200 teens about to graduate from a rigorous five-and-a-half month paramilitary program run by the Army National Guard, called Sunburst Academy.

ABC7’s Miriam Hernandez has the story. Here’s a clip:

At just 12 years old, Junior led police on a chase while under the influence.

“It went really bad,” Junior said. “I was not going to school, I was doing drugs.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Jerry Ambriz said by age 16, Junior was both lost and hardened by struggles on the streets, at school and at home.

Ambriz tried to guide him through a sheriff’s program called Vital Intervention and Directional Alternatives, or VIDA.

But Junior said he hated it and quit. Ambriz warned him about a life of crime.

“I promised we would meet up again,” Ambriz said.

Way to go Deputy Ambriz!

The communities in Los Angeles County are in need of more Law Enforcement Officers such as yourself.

VIDA was started by a few of my old partners at ELA. I am currently in Juvie Courts and will see if the Judges are aware of this additional program. Good Job Ambriz, GO LOW PROFILE! 2 Remember the Cave Man!

Good for this youth and big kudos to this Deputy. Nice to read something about one of

the many positive hard-working members of the justice system!