More than eight months into the coronavirus crisis, California’s prison system is full of incarcerated people and staff sick with the virus.

Over the last month, especially, the reported number of infections in California’s prisons has exploded to more than 5,500 imprisoned individuals and 1,800 staff with confirmed cases.

At the end of October, there were 564 people with active COVID-19 cases living in state lockups.

By November 19, around the time that the CDCR announced that it would test the entire prison population, there were 2,056 incarcerated people with coronavirus.

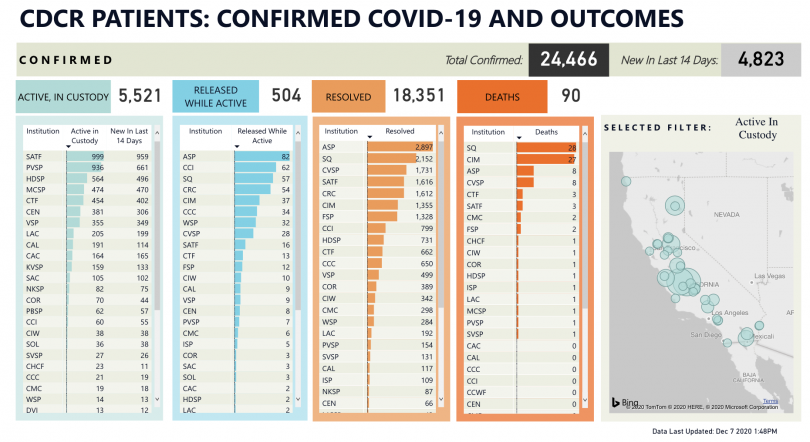

On December 4, the department recorded 4,076 active cases. Three days later, more than 1,400 additional people had tested positive for the virus, thrusting the count to a record high of 5,521 cases.

More than 4,800 of the 5,500 active cases were recorded in the last 14 days.

Pleasant Valley State Prison and the Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison in Corcoran each have nearly 1,000 active cases each. Ten other prisons have between 100 and 600 active cases.

As of mid-November, every facility with 10 or more active coronavirus cases has started weekly testing of all staff and inmates in the facility. A number of housing units throughout all institutions have been put on quarantine as a precaution to potential COVID-19 exposure. While on quarantine the population is closely monitored, and tested for COVID-19.

So far, 90 imprisoned people and 10 staff members have died after contracting the virus. Five of those incarcerated people died between November 26 and December 2. And as of December 3, there were 54 more receiving treatment in outside hospitals.

Overall, there have been 24,239 coronavirus infections among the incarcerated population, which stands at 97,254.

As of the last count on December 4, there were 1,822 guards and health care workers with active COVID-19 cases, with 1612 of those reported in the previous 14 days. Over the more than 8 months of the pandemic, a total of 6,939 staff members have tested positive, according to the department.

All facilities across the state are in the middle of another 14-day modified lockdown limiting movement of staff and incarcerated people to reduce further spread of the virus. Yet advocates and lawyers say more people must be released to make a measurable impact — especially medically vulnerable and elderly prisoners.

The state has reduced the prison population by around 20 percent (a drop of approximately 23,000 people) since the start of the coronavirus crisis, by limiting intake from jails combined with just under 10,000 regular releases, as well as early-releasing around 6,600 people who were already close to the end of their sentences. And those early releases have slowed significantly.

During the first month of the early release program, between July 10 and August 9, approximately 4,400 people were released early (within 180 days of their regularly scheduled release dates). Between October 5 and November 4, there were just 437 early releases.

“As the number of early releases dwindles, and intake increases, CDCR’s total Prison and Camps population has essentially plateaued, and may slowly increase,” the attorneys from the Prison Law Office, one of two law firms representing imprisoned people in lawsuits challenging conditions inside state prisons, wrote in a November 18 court filing.

Prisons were still operating at a combined 105 percent of design capacity as of mid-November.

Additionally, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra has proceeded to fight proposed releases in court.

Over the last 8 months, prison numbers have continued to drop in some states, but “not quickly or significantly enough to slow the spread of COVID-19,” writes Prison Policy Initiative’s Emily Widra in a recent report on coronavirus behind bars.

Californians are not the only imprisoned people facing massive COVID-19 outbreaks.

“The Texas prison system alone has had more COVID-19 cases than in four states and Washington, D.C. combined,” according to PPI.

(Jail populations, too, have gradually ticked upward after taking a steep COVID-19-induced decline between March and mid-May.)

In August, the ACLU launched a campaign pressing governors to use their executive clemency powers to free 50,000 of the 1.3 million people in state prisons, starting with people locked up for technical probation or parole violations, elderly prisoners, people who are serving harsher sentences than they would receive if they were sentenced for the same crime today, and people convicted of drug possession and distribution crimes.

A recently released Urban Institute report looks at how governors can harness their clemency powers to swiftly and significantly reduce prison populations to reduce mass incarceration, which would also help states better protect those living and working in the close quarters of prison facilities.

“Just as the policies that fuel this crisis were all the product of a governor’s signature, governors can use that same stroke of a pen to remedy this … freeing people with an efficiency unmatched by other government actions,” the report says. “Unfortunately, today, commutations tend to occur rarely and are often granted to a small handful of people. For commutations to be an effective response to mass incarceration, governors must use their commutation powers in new, transformational ways.”

In California, Governor Newsom has reviewed and granted some clemency petitions but has not increased output during the pandemic.

Since he took office in January 2019, the governor has granted 63 pardons and 78 commutations. Newsom recently granted four medical reprieves to individuals at great risk of serious illness or death if they caught the coronavirus.

Thousands more elderly and medically at-risk individuals remain in lockup, however.

The Urban Institute report notes that mass-clemency actions taken on behalf of individuals in a certain category — rather than the usual case-by-case method — are by no means unprecedented.

Last year, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker mass-pardoned more than 11,017 people convicted of low-level marijuana offenses.

And, this February CA’s governor penned an executive order launching a new clemency system meant to address past decades’ discriminatory criminalization of LGBTQ+ people.

There have also been a number of instances in which governors have used executive clemency specifically to reduce prison populations to address severe overcrowding.

“There is deeply rooted legal precedent for executives — governors and presidents — to wield their executive clemency powers to grant commutations to large categories of people,” the UI report says. “That precedent, combined with notable examples of individual grants of clemency, provides a clear model for governors today to use in evaluating, shaping, and executing mass commutations for people who are trapped in their state’s prisons.”

Sadly my daughter was wrongly sentenced to 1st degree murder due to being honest. If she had of taken their plea bargin and agreed with the police saying she planned to murder him she could have gotten 16 years. Now she will have to lie anyway in order to be released saying yes it was planned. It should have been involuntary manslaughter but her attorney was too consumed with becoming a judge among many other things to represent her properly. Her Attorney did however put on paper that she didn’t represent her properly but that didn’t grant my daughter an appeal hearing, it was thrown out. I wonder if it would have mattered if her attorneys husband would have been there at the trial, like I was promised, also being an attorney? As we were told me he would be, but he decided to go river rafting at the last minute instead.There were even people who saw her deceased boyfriend strangling her previous to this event. So now my daughter who was abused by the man she accidentally killed is in prison for life, my retirement money went to her attorney, and her baby (who was also abused by same man) is being raised by me with no mother or father, struggling with PTSD. Justice, what is that?