Arrest rates for youth have fallen nearly 75 percent since a high in 1994, but despite the stats, black kids who are arrested—particularly young black males—are disproportionately tried in adult courts, and sentenced to adult prisons, according to a joint report released Monday by the Campaign for Youth Justice (CFYJ) and the National Association of Social Workers (NASW).

Unfortunately the out-of-whack numbers don’t appear to be getting better over time, according to the new report, The Color of Youth Transferred to the Adult Criminal Justice System: Policy and Practice Recommendations, In fact, in some areas of the U.S., the disproportional percentages are the highest seen in 30 years of data collection.

Black youth are approximately 14% of the total youth population, but 47.3% of the youth who are transferred to adult court by juvenile court judges “who believe the youth cannot benefit from the services of their court,” write the report’s authors.

For instance, black youth are 53.1% of youth transferred for person offenses despite the fact that black and white youth made up an equal percentage of youth charged with person offenses, 40.1% and 40.5% respectively, in 2015.

The new report points to decades of research showing that children sent to adult jails and prisons are more likely to die by suicide, suffer from mental illness, and more likely to be abused when in side. These same kids, once they are released back into their communities, are far more likely to recidivate than kids convicted of the same or similar crimes, but who are kept in the juvenile justice system.

“Research has proven that adults courts and jails are no place for children,” said NASW Social Justice and Human Rights Manager Mel Wilson.

Matters are further complicated, according to Wilson, by the fact that youth involved in the justice system are statistically far “more likely to have mental health needs, and have suffered from trauma,” thus requiring rehabilitation and treatment services “that are not provided in most adult jails.”

Deep dives and recommendations

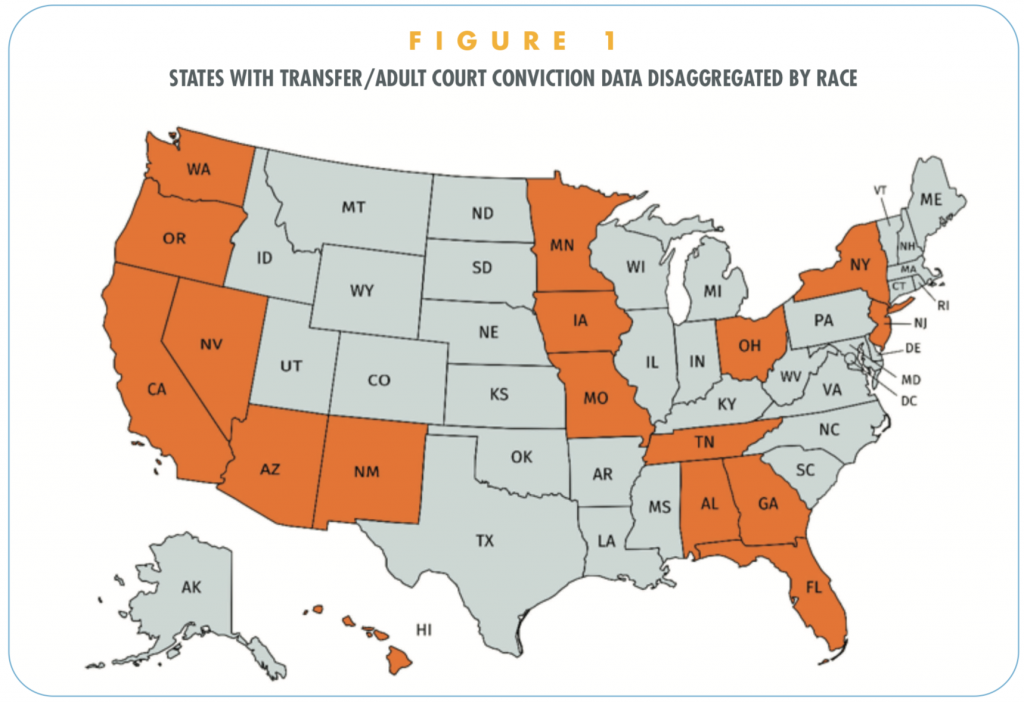

The new report was somewhat limited in some of its research since many states don’t publish their data about youth transfers. As of 2018, only 35 states and Washington, DC, have published data within the last five years showing numbers of juvenile transfers to adult court, and youth convicted in adult court. Of these jurisdictions, only 18 disaggregated data by race.

States with transfer and adult court convictions disaggregated by race, courtesy of Campaign for Youth Justice (CFYJ) & the National Association of Social Workers (NASW)..

(California does both, but we’ll get to that in a minute.)

Thus, in order to show how and why black kids are so disproportionately represented in the nation’s adult justice system, the new report’s authors took a deep dive into the issue in three states: Oregon, Florida, and Missouri, and looked at how black youth wound up at the front door of adult courts so frequently.

As part of their research, the report’s authors also into what they described as “the historical context of racial terror inflicted on black communities” that they said is a part of what has “shaped the foundation of systemic policies, practices, and procedures that compound disproportionality.”

This interweave of information makes for interesting reading.

For instance, the report notes that, in 1844, the Legislative Committee of the Oregon Territory enacted a racial exclusion law, which made it illegal for “black or mulatto” individuals to live in the territory of Oregon. And it was not until 1973 that Oregon’s legislature passed a resolution re-ratifying its support of the Fourteenth Amendment. (For those who have forgotten, that’s the amendment that provides full citizenship to African Americans and other people of color born in the United States.)

Now, black youth are only 2.3% of the state’s youth population, yet black youth represented 15.8% of the Oregonian kids transferred to adult court.

The authors aren’t exactly positing to any kind of direct cause and effect. But to deny the correcting threads between past and present, they suggest, is to turn one’s back on the facts.

When it came to their case study of Florida, the authors pointed to the 2017 report, Lynching in America, by the Equal Justice Initiative, which documented that 12 American states were “the most active lynching states’ in the country. Florida, as it turns out, is not only one of the 12, it was among the top four states with the highest statewide rate of lynchings in the U.S.—along with Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Fast forward to today in Florida, which has the highest publicly reported number of youth direct filed by prosecutors into adult court system in the nation, and the highest “day count” of youth in adult prisons.

Broken down by race, although black youth are only 21% of the youth population, in 2016, they accounted for 67.7% of the mandatory and discretionary direct file transfers of youth to adult court.

Furthermore, according to the new report, black youth’s prison sentences in the adult system were 7.8% longer than white youth’s sentences for the same type of offense.

Yet the CFYJ/NASW report makes clear that it is not about finger-pointing. It’s larger intent, write the authors, is to use these past and contemporary lenses and data to highlight what advocates and local and state officials can do to overcome the impact of “historic and ongoing racism.”

Where California fits in

As mentioned above, California is one of the states that both publishes their youth transfer data, and disaggregates that data by race.

But, while California is not one of the states profiled, a look at our 2015 data on juvenile transfers and conviction reveals sobering numbers, especially when it comes to race.

(You can find that data and a lot more right here.)

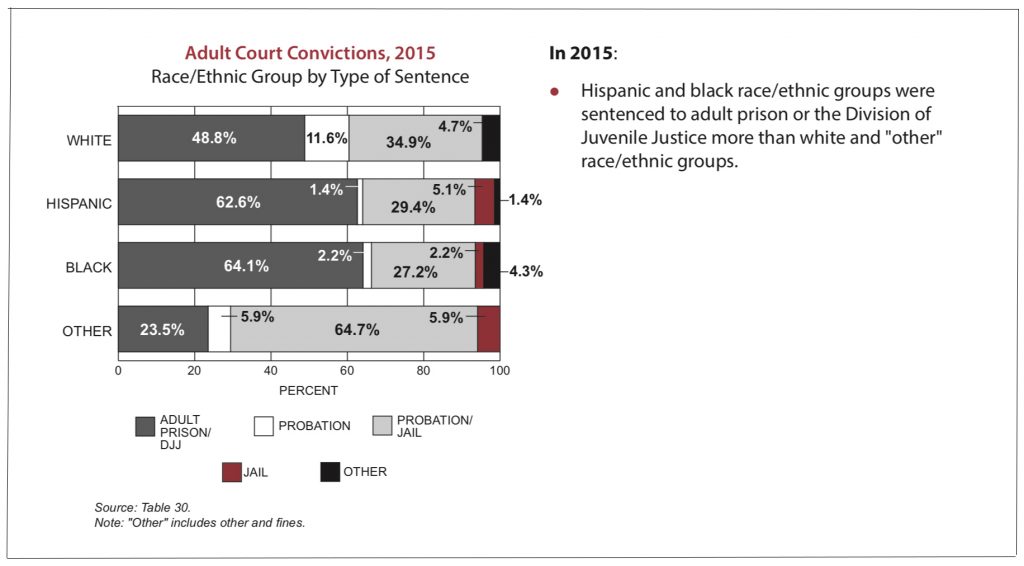

For instance, the California data showed that all California youth who were tried in adult court had a high percentage of convictions regardless of their race/ethnic group.

Yet, when it came to the sentences handed down to those kids who were convicted in adult court, Hispanic and black race/ethnic groups were sentenced to adult prison (or the state-run Division of Juvenile Justice—prison for kids) far more often than white and “other” race/ethnic groups. And black kids were sentenced to lock-up the most often of all.

(You can find the exact stats on pp: 50-53 of the California Attorney General’s 2015 report.)

The good news is, withe the passage of Prop. 57 in 2016, while prosecutors can recommend that a kid be transferred to adult court, they can no longer “direct file,” a youth into being tried as an adult. That power has been reverted back to judge’s who are statistically more likely to look at a greater number of mitigating factors before transferring kids to adult courts and then on to adult prisons.

Unfortunately, as WLA reported late last year, the state has a long way to go in curing racial disproportionality when it comes to such transfers: During the five year period from 2010 to 2016, for every white youth in California sent to adult court, 3.9 Latino kids and 12.3 black kids were transferred to the adult system to be tried.

And in 2016 alone, black youth were 8.5 times more likely than white youth to be tried as adults. Latino kids were almost three times as likely.

“This brief dives into the historical context of racial terror inflicted on black communities that has shaped the foundation of systemic policies, practices, and procedures that compound disproportionality,” said CFYJ Policy Director Jeree Thomas of what the report documents.

Yet Thomas sees solutions on the horizon.

“This is a symptom of chronic and systemic racism beyond the confines of the justice system itself, but we believe that intentional advocacy and transformative thinking by social workers, attorneys, youth advocates, and system leaders can begin to redress this issue in states across the country.”

May it be so.

[…] She noted that the skewed arrest data is amplified even more as Black kids move through the system. Black youth are five times more likely to be detained than white youth, and are more likely to be tried as adults for the same offenses. […]

This is a really poor article. The article makes no serious effort to look into relevant facts behind the apparent disparities discussed. Whilst there may be a racial bias and prejudice in the US CJD at play, it does nobody any favours to deliberately obscure and distort salient facts. For a start, according to the Office of Justice Programs (of the US Department of Justice) there were 430 homicides and non negligent manslaughters committed by black youth in 2019, compared to 410 by white youth. As the black youth population is ~20% and the white population 75%, that means black youth are ~3.75 times more likely to commit a murder than white youth, and 4 times more likely than a youth of any other race. The crime of murder is far more likely to be tried in an adult court, and this is clearly one reason behind the apparent “disparity”. If we assume that every youth murder case is tried in an adult court, then yes, the factor 4 is indeed lower than the factor of 18 cited in this article. However, there are other factors that the article does not explore properly. If the accused has a previous violent criminal history, then that is far more likely to result in his/her serious crime case being tried in an adult court. Whilst I won’t cite any numbers here, the reader is free to research the facts relating to criminal records, age and race. For whatever reasons, black youth are far more likely to have a significant violent recorded criminal history at the time they are charged with a serious crime (not necessarily murder), and then the state prosecutor has little choice but to try the accused in an adult court (let’s not forget the victims here either!). When you take these facts into account, you can quickly get to the factor of 18 mentioned in the article. Also, when it comes to sentencing, previous criminal history plays a huge role. People (youths and adults) with a previous criminal history usually get longer sentences when convicted and sentenced for a new serious crime. The length of sentence depends on the gravity of the crime in question, and the extent of criminal history. They accused may even have a previous suspended sentence. This is what judges are for, to take into account mitigating or aggravating factors and use their discretion in sentencing. So if sentencing is racist, then the article is essentially claiming that US judges are racist. But without accurately compiling and presenting proper stats on the severity of the crimes the accused are being charged with, the relevant aggravating factors, and the extent and seriousness of the accused’s criminal histories, you cannot make that claim in good faith. The US CJD may be systemically racist, but this article does absolutely nothing to prove it.

Apologies, the factor of 18 I mentioned (for black youth to be more often tried in an adult court than white youth) was not cited in this article. It is, however, quoted in other articles on the subject.

This logic ignores the roots of white supremacy and discrimination upon which the Us criminal justice system was founded. Even the charges brought will be implicated the the race of the accused. For example, a white child would be less likely to be accused of lesser charges in the same setting where the black youth is charged with homicide. So, we must look even more closely at these disparities and recognize the systemic racism at play.