During the nearly five decades that Roe v. Wade has been considered to be settled law, the courts have repeatedly confirmed that incarcerated people also retain this constitutional right.

That doesn’t, of course, mean that this constitutionally guaranteed right was honored.

Now, of course, for the first time in nearly half a century, these same rights are under attack, as demonstrated on December 10, when the newly-constituted U.S. Supreme Court only barely disrupted SB 8, the Texas law that outlaws abortions after six weeks of pregnancy, then enforces the new law with a form of legal vigilantism that deputizes anyone who would like to sue any and all Texas residents who might possibly have “aided or abetted” anewly non-permitted abortion in any way, and thus collect a $10,000 bounty.

“Aiding,” it seems, could include the Uber driver who got a woman to a clinic, or a best friend who researched for the pregnant woman which clinic was the closest.

Next, SCOTUS will rule on the 2018 Mississippi law, which bans abortions outright after 15 weeks.

So, now that such rights are under attack throughout the nation, and state legislatures have enacted 90 abortion restrictions in the first half of 2021, the most of any year in U.S. history, what is the situation for those who find themselves living behind bars when they are pregnant?

With the above new legal landscape in mind, Prison Policy Initiative researchers Katie Rose Quandt and Leah Wang, have released a new report, which examines what kind of choices are available to women inside U.S. jails and prisons, if they find themselves pregnant in lock-up, and how those policies might change should Roe be overturned.

To explore these questions, Quandt and Wang analyzed two studies recently published in two different medical journals, each of which analyzed incarcerated people’s access to abortion across 22 state prison systems and six county jail systems.

“Life behind bars does not occur in a bubble,” write the Prison Policy Initiative authors in their new report, “and these state policies have implications for the estimated 58,000 pregnant people who enter jail or prison each year.”

The two main studies that Quandt and Wang examined reveal that, as you might guess, abortion and contraception access varies greatly between states — and that, unsurprisingly, that there are correlations between the state’s abortion policies and access to abortion behind bars.

For example, only three of the 22 state prison systems studied banned abortion entirely. And all three of those states, which banned abortion in prison, were states that had policies that were considered “hostile” to abortion rights.

In all, 77% of state prison systems in states “hostile” to abortion rights, allowed abortion for incarcerated people, compared to 100% of prison systems in “non-hostile” states.

Second trimester abortions were allowed for incarcerated people in 38% of hostile states and 67% of non-hostile states.

When looking at the policies for jails, the PPI report found a similar pattern. Both of the jails examined, which were located in a hostile state (Texas), banned any and all abortions for incarcerated people, while all four jails studied that were in non-hostile states allowed abortions in both the first and second trimesters.

Still, even in states that officially allow abortion, the two PPI researchers found that many incarcerated people were still effectively blocked from obtaining the care they needed due to such barriers as the requirement for the pregnant person to pay for their abortion, a barrier that for many proved simply insurmountable. In other cases, the physical distance between the prison or jail, and the abortion caregivers, became the deal breaker.

All in all, wrote the PPI report’s authors, the “studies make clear that people behind bars often have very few — if any — choices and autonomy when it comes to their reproductive health and decisions.”

In brief, here are some of the report’s main findings.

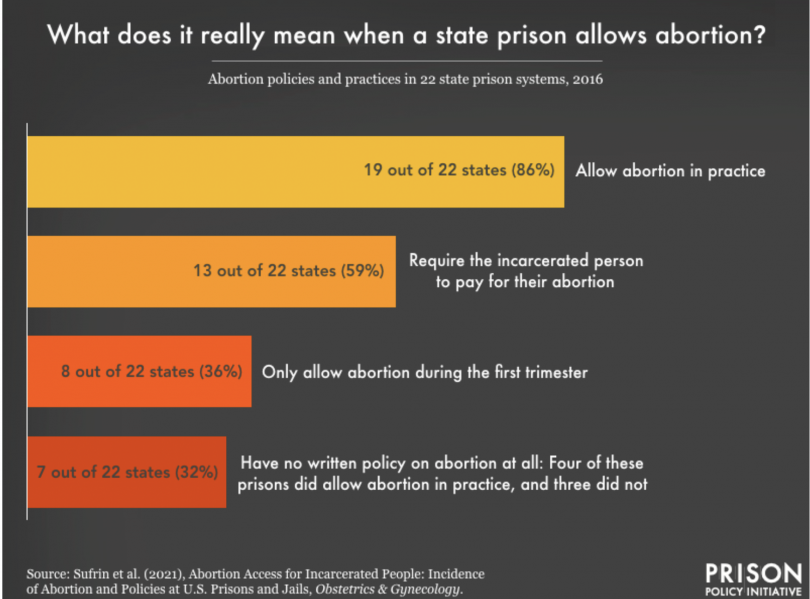

- Most state prison systems (19 of the 22 studied, or 86%) allowed abortion, whether it was written policy or not. Of these, eight allowed it during the first trimester only.

- Seven state prison systems (32%) did not have an official written policy regarding abortion. While four of these states did allow abortions in practice, “the lack of policy is concerning,” wrote the report’s authors, “and may leave individuals’ access to the discretion of prison staff.”

- Three prison systems did not allow abortions at all. None of these three had an official written policy on abortion access, “but in practice they did not allow any access, and did not indicate exceptions for rape or incest, in violation of the U.S. Constitution.”

- Most jails (4 of the 6 studied) allowed abortion. The two that banned abortion were both in Texas. Namely the Harris County jail in Houston, and Dallas County jail system.

- The four other jails studied allowed abortion during both the first and second trimesters.

- The researched studied by the PPI report indicated abortions are “relatively uncommon behind bars.” Over the one-year course of the main study the PPI authors looked at, there were 33 abortions reported in the jails the study followed, and 11 in the study’s prisons, out of the 1,040 total reported pregnancies in all of the facilities studied.

The Prison Policy Initiative report also looked at the related issue of contraception, which is a critical matter for many women in prison who are pre-menopausal. When it came to contraception, the PPI researchers discovered that, in six of the prison systems studied that allowed access to permanent contraception, those same prison systems did not allow accesses to reversible contraception.

This means that, in those six state systems, incarcerated people who want contraception may be forced to choose between permanent sterilization or no contraception at all.

California is, of course, one of the more liberal states on the topic of abortion, both in state prisons and county jails—at least in terms of its laws.

Yet, in a 2014 audit of California prisons performed by the state auditor, the auditor’s office found that 144 women — particularly women of color — were subjected to illegal sterilization procedures between 2006 to 2010, in which all but one the 144 bilateral tubal ligation procedures that occurred, were performed without the necessary approvals.

In some of those cases, according to the auditor, the women who were sterilized had no idea that their surgeries would prevent them from ever getting pregnant.

In many of the cases, prison medical staff simply requested approval for some other medical procedure—such as a cesarean section— and “did not indicate that the inmate was also to be sterilized.”

In another devastating case, in 2020, a whistleblower alleged that an immigration detention center was conducting mass hysterectomies that one detained woman compared to an “experimental concentration camp.”

Historically, the report’s authors noted, forced sterilization has disproportionately devastated the lives of Black, Indigenous and other women of color.

Furthermore, as with abortion, “many facilities did not have a written policy regarding contraception,” meaning actual access in those states might fall to the discretion of staff members.

“Pregnancy overlaps with incarceration often enough that prisons and jails should have clear policies and procedures to screen for pregnancy, provide quality prenatal and postnatal care, and ensure that incarcerated people have access to safe abortions, deliveries, and contraception, as they are entitled to by law,” the authors wrote.

“People do not lose their constitutional right to reproductive autonomy when they are incarcerated.”

Yet, the two recent studies that PPI examined reveal abortion and contraception policies—in the way they are actually practiced—are often unconstitutional, and “frequently undermine individuals’ autonomy.”