On January 30, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors received a new five-year plan for closing the dangerously decrepit Men’s Central Jail without a replacement facility. This new plan isn’t the county’s first roadmap for shuttering the jail, nor is it the most expedient.

In August 2019, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors made the historic decision to cancel a $1.7 billion contract to replace the jail, and to commit that money to implementing a “care first, jail last” ethic, instead. Six months later, the Alternatives to Incarceration Workgroup (ATI), which was born of this decision, and composed of county leaders and community representatives, brought the supervisors a final report with 114 recommendations for implementing a “care first” justice system.

Then, in July 2020, the supervisors directed the LA County Sheriff’s Department and the Office of Diversion and Reentry to launch a workgroup to come up with a plan for closing MCJ within a year.

In March 2021, the Men’s Central Jail Closure workgroup came back with a detailed 146-page plan for closing the jail, not in the hoped-for year, but in 18-24 months.

Since then, the board has continued to delay, while calling for more reports back. In 2022, the supervisors set up a brand new county department — the Justice, Care, and Opportunities Department (JCOD) — as a hub for “care first” programs and services, as well as efforts to close the jail.

Now, at the supervisors’ request, this department has come back with a new, five-year timeline for closing the jail.

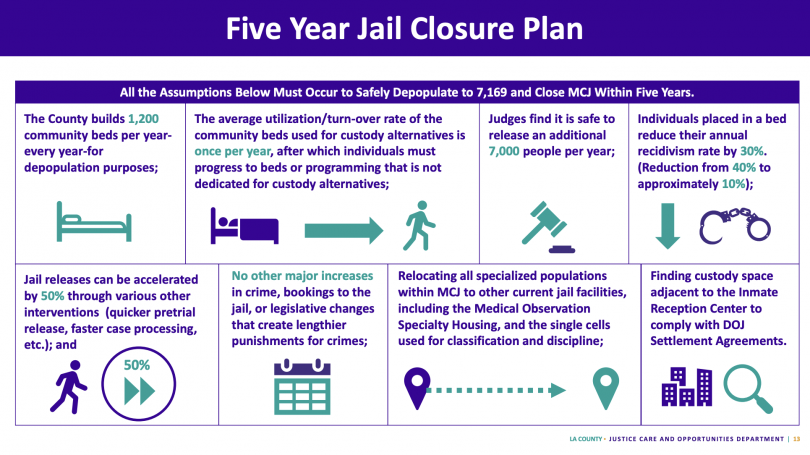

Under the new plan, the county would need to come up with 1,200 new community mental health beds each year, JCOD’s executive director (and former county superior court judge) Songhai Armstead told the board on Tuesday. These beds must not serve as long-term placements, but must be turned over every year. This means that the county would have to ensure there were enough additional placements for people needing permanent care.

The plan also calls for the release of 7,000 additional people from the jails per year. The county can reach this goal in a number of ways, according to Armstead. Individuals could be released to secure beds, electronic monitoring, or another program.

“We don’t have any influence over what the courts will do,” the former judge said, “but they would have to feel comfortable releasing 7,000 people per year,” out of the approximately 60,000 that come through the jail system annually.

The recidivism rate would also need to drop, Armstead said. And the speed of case processing must increase by 50%.

In addition, the county would also have to relocate people inside Men’s Central Jail with special needs, who consequently would not qualify for diversion or release.

“We have a bunch of single cells, a bunch of keep-aways there,” said Armstead. “We would have to find existing space within the county system, and complete the construction to fully move those people out to another facility that is safe and humane.”

According to last Tuesday’s report to the board, 53% of the people currently in Men’s Central Jail are receiving services for mental health issues. Approximately 52% of the population is being held pretrial, and 65% of the pretrial individuals have been accused of serious or violent crimes.

To reduce the county’s jail population enough to close Men’s Central Jail, Armstead said, “we are going to need to address those with high needs and more folks with serious or violent charges.”

Meanwhile, the conditions inside the jail make the facility “uninhabitable,” said Armstead.

“If we’re waiting for a perfect population, we’re doing a disservice to those who are incarcerated,” the former judge said. “We’re not able to heal them, help them, program them, anything that really amounts to public safety or healing, and we’re releasing people into the community in an unfair state and without the support that people are entitled to and deserve.”

More importantly, the county is leaving incarcerated people in dangerous conditions by keeping the jail open.

At least 49 people have died in LA’s jail system since the start of 2023 — at least 46 people the previous year, and there have been three more deaths in January.

“I think it is really, really embarrassing at this point, that the Men’s Central Jail is not closed,” Megan Castillo of the Reimagine LA Coalition said during Tuesday’s public comment period.

Castillo pointed out that the supervisors have had the MCJ Closure Report for almost three years, without measurable progress.

“Time is of the essence,” said Castillo. “People are dying and languishing in our jails.”

You mean no more hunting down an employee toilet that works in the men’s locker room @ MCJ and using one ply for toilet paper while listening to some outdated music emitting from an ancient Yellow BoomBox that God knows how long it’s been playing continuously for lmao!

Does MCJ need to close? Yes. Can the most populated county jail in America operate without replacing it? No. This is yet again another push of victim devaluation.

There is no larger county in America. Rather than continuing to throw crap against the wall to see what sticks, why isn’t the county actually tapping into the sparse institutional knowledge that remains within the jails on how to logically address the true needs of the inmate population?

The BOS has OIG and COC, why bring in someone that knows nothing about how this department works internally? This “plan” puts even more emphasis on other areas that have nothing to do with public safety. If (when) this fails (just like AB109 and Prop 37), then the county will need to build a jail to replace MCJ, like they should’ve done decades ago.

The current BOS isn’t fully responsible for this delay, but they are in place to make a decision that will affect those that succeed them. The previous supervisors are to blame as for the conditions of confinement, and this has had a detrimental effect on LASD.

This dog and pony show is really lame; and sadly the public will end up paying the price.

Tradition of Service – Well sad and Amen.

[…] the BoS solicited a plan from a newly created department that would enable the jail’s closure in five years. More than 130 people have died in MCJ since […]