On Tuesday, September 12, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to set aside $88 million in Measure J funding for alternatives to incarceration meant to help the county shut down the dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail.

Measure J, a ballot initiative approved by voters in 2020, amended LA County’s charter to permanently set aside at least 10% of existing locally-controlled, unrestricted revenues to be directed to community investment and alternatives to incarceration starting in fiscal year 2021-22.

Now, the county is three years into Measure J’s implementation, and more than four years beyond the supervisors’ historic 2019 decision to cancel a $1.7 billion contract to replace Men’s Central Jail with a new carceral facility, and to instead fund things like pretrial services and community-based care upstream from incarceration.

The jail closure process was supposed to take 12 months, but the timeline was later stretched to an estimated 18-24 months. Even with this extended schedule, follow through from the county has been slow and patchy at best, with very little tangible progress toward closing the jail.

Part of the problem is that the county is failing to fully fund Measure J, thus shorting what the county calls the Care First Community Investment program (CFCI), much to the consternation of community advocates.

Meanwhile, people in LA County’s jails, most of whom are incarcerated pretrial, are being held in inhumane conditions and dying in custody at an alarming rate.

County and advocates disagree about what 10% of unrestricted revenue means

At the time of Measure J’s passage, LA County’s then-CEO Sachi Hamai estimated that 10% of locally-controlled, unrestricted revenues would come to between $360 and $490 million per year. This money would then be spent on things like diverting more people from jail, ramping up pretrial services, and investing in services for youth.

Thus, when the recommended budget for fiscal year 2021-22 appeared, the first year of Measure J implementation, community leaders were surprised to find an allocation amount far lower than that initially projected $360 to $490 million per year.

According to the Chief Executive Office, now led by Fesia Davenport, the county should fund the Care First efforts with a “down payment” of $100 million in Measure J funding that would be ramped up over three years to ultimately land at a $300 million allocation for fiscal year 2023-24.

Community members pushed back, calling in and showing up to board meeting after board meeting to urge the supervisors to fully fund Measure J immediately — not in three years.

That same year, Measure J came under legal fire when Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Mary Strobel ruled that the ballot initiative was unconstitutional, after a coalition of 14 unions, including the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (ALADS), filed a petition for peremptory writ of mandate prohibiting enforcement of Measure J.

According to Judge Strobel, the board should have control over how unrestricted funds should be spent. Restricting those funds to predetermined allocations, she said, went against the county’s charter.

To the board’s credit, the supervisors chose to continue to allocate Measure J money while the issue of the constitutionality of the ballot measure was working its way through the court system.

Finally, this summer, on July 28, 2023, a decision from California’s 2nd District Court of Appeal reversed the judge’s ruling.

Hitting the third year of implementation this year should mean that the county spends at least $300 million (although advocates say the number should be higher).

Instead, as of September 12, 2023, the county has only come up with $88 million in Measure J funding for FY 2023-24.

Supervisor Janice Hahn said she was disappointed that the county couldn’t drum up another $12 million to hit the $100 million mark for this year, making a total of $300 million over the first three years.

“The more money we can spend in our communities,” Hahn said, the more incarcerations the county can prevent. “We can prevent more people going into our jails, we can have better, stronger youth development in this county, we can have more job training and more after school mentoring, tutoring.”

But this new goal of $300 million total over three years that the county is struggling to reach is not the $360 to $490 million per year that former CEO Sachi Hamai, projected.

It’s not even close to what the county proposed in 2021, which was to steadily increase funding over three years, with annual expenditure hitting $300 million in 2023-24.

WitnessLA found the math to be confusing from the beginning. So, we emailed the LA County CEO for clarification on the issue in April 2021.

The office told us that, while it was impossible to know exactly how much locally generated unrestricted revenue the county would raise in the future, they estimated that “the full annual set-aside for Measure J in FY 23-24 would be $300 million.” The email also stated that the county had “3 years to ramp up to full funding for Measure J.”

So, it appears that in 2021, the county expected to spend $300 million in 2023-24, not $88 million, or even $100 million.

This abandoned plan is still a long way from what advocates expected when Measure J passed.

Community leaders, including those who served on county Care First and Measure J workgroups, have argued that fully funding Measure J by 2023-24 should mean the county spends more like $900 million this year.

To make matters worse, the county has not yet spent all of the money set aside under Measure J for the previous fiscal year, 2022-23. Last year’s delay was partly due to a failure to hire a Third Party Administrator to distribute funding to local organizations in a timely fashion.

Yet, the shift away from dangerous jail settings and toward community-focused alternatives to incarceration cannot wait, community members continue to remind the board.

“Families are asking you to prioritize the closure of Men’s Central,” said Ambrose Brooks, of the Justice LA Coalition and Dignity and Power Now. “The community is asking, and the demand is not unreasonable. Set a concrete timeline with benchmarks for funding, with benchmarks for population, to close Men’s Central Jail by March 2025.”

Brooks’ colleague Janet Asante, was even more emphatic. “This is an emergency,” she told the board, “and we need you to treat it like one.”

Deadly jails

One critically urgent reason to reduce incarceration is that people keep dying in LA’s inhumane jails.

Most of the deceased have been men of color who were being held before trial because they could not afford bail.

Between 2005 and 2019, LA County had the highest rate of in-custody deaths among 53 California county jail systems, according to a 2020 investigation by the Redding Record Searchlight.

So far this year, more than 30 in-custody deaths have been reported, and there’s at least one fatality the LA County Sheriff’s Department has failed to include in its death count.

According to a quarterly report from the LA County Office of the Inspector General dated August 16, a total of seventeen people died in the custody of the LA County Sheriff’s Department during the three months between April 1, 2023, and June 30, 2023. Eleven of those people died in the county’s jails, one died in a cell in the East LA Sheriff’s Station, and five died after being transported to hospitals. During just one week in August, three people died in Men’s Central Jail.

Some of the families whose loved ones died in LA’s jails attended the meeting to address the board about the deaths, about conditions within the jails, and about the pressing need for community investment.

Helen Jones’s son, John Horton, died in jail in 2009, at age 22, where he was being held in solitary confinement after failing to show up at a court-ordered drug treatment program. “I was here 14 years ago crying about my son, John Horton, trying to raise the voice of how many inmates were dying” back then, Jones said. “So to stand today and see 33 deaths and nothing being done about it, and all these families here — it is really sad.” Jones urged the county supervisors to find a way to get the funds to the organizations already on the ground working to save lives.

An uncounted death

If Stanley Wilson Jr., a 40-year-old former professional football player for the Detroit Lions, had received community-based mental health treatment instead of a jail cell, he’d still be alive, his family said.

Instead, Wilson died on February 1, 2023, while being transported from jail to the hospital, according to the sheriff’s department.

“He had been deemed incompetent to stand trial, and was housed in Twin Towers until his death,” his mother, Dr. D. Pulane Lucas said during the board meeting.

“While it’s too late for Stanley,” Dr. Pulane Lucas said. “I’m here to speak to the importance of providing needed services for inmates with mental health services, and also to support alternatives to incarceration.”

Stanley was her only son, she said. “He was a student leader and track star, a standout football player at Bishop Montgomery High School and Stanford University” followed by his career in the NFL.

The autopsy suggested that Wilson had a pulmonary embolism. Yet the coroner also gave a post-mortem diagnosis of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease caused by repeated head trauma, and common among football players.

Yet, the family said they were surprised to also find wounds on Wilson’s body — including bruising around his wrists and a head wound.

Wilson’s family, who finds the circumstances surrounding his death to be suspicious, is suing the sheriff’s department, after being denied answers and requested footage from CCTV cameras in the jail.

“If I were not here today, you might never know of Stanley’s death,” his mother said. “It was not recorded in the LASD online database.”

The LASD’s database of in-custody deaths does not list a death on February 1, the day Wilson died, nor do any of the other deceased individuals listed match Wilson’s age, sex, and race.

After Dr. Lucas shared her son’s story during public comment, Supervisor Janice Hahn reminded speakers to stay on topic. If they were going to talk about their loved ones’ deaths in custody, they needed to tie their comments to the issue of funding CFCI, “just for our County Counsel’s comfort.”

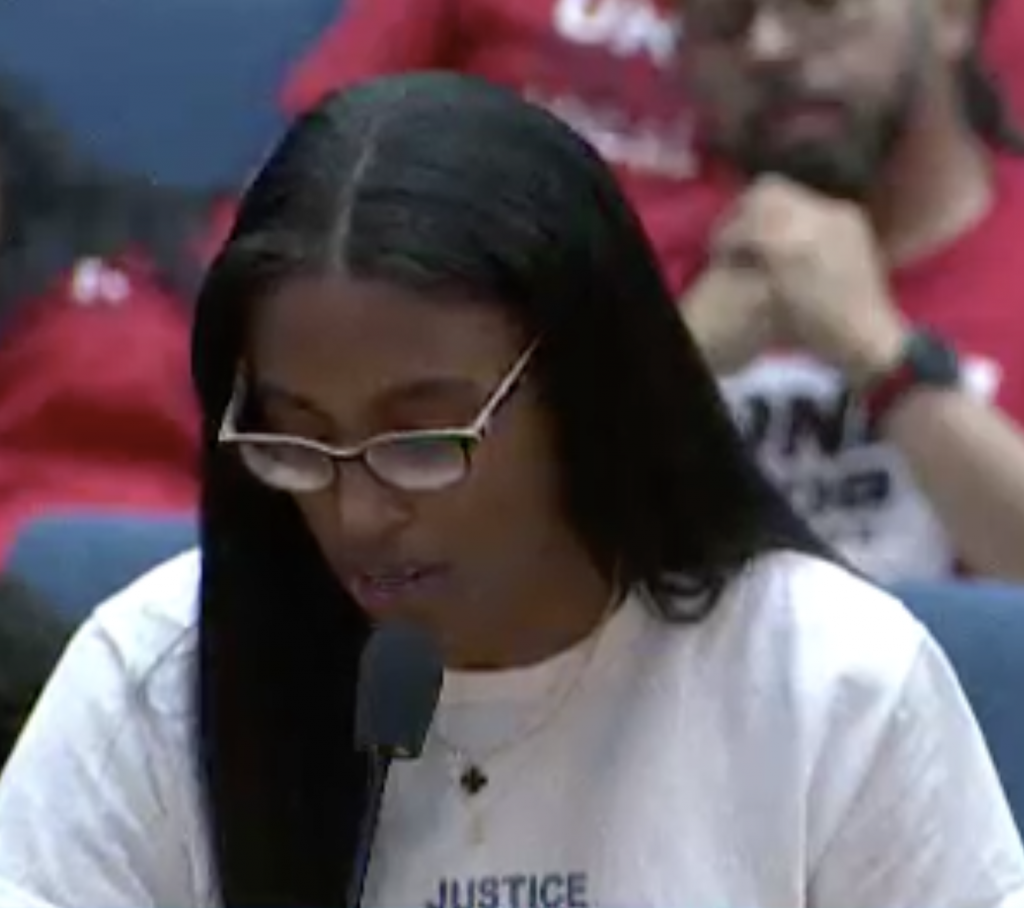

Fredericka Lucas addresses the LA County Board of Supervisors on September 12, 2023.Wilson’s sister, Fredericka Lucas, also addressed the board regarding her brother’s death, noting that telling his story was relevant to the matter of CFCI funding because Wilson, who was reportedly arrested on a minor trespassing-related charge, needed mental health support, but died in custody instead.

It was difficult, not knowing what really happened to her brother, Lucas told the board, She spoke about the department’s failure to release footage to the family, and noted that her family had “questions about the reported cause of death, the autopsy reviewing process, and whether the medical examiner did due diligence in providing outside medical perspective,” she said. “LA County needs to support and treat inmates with —.”

At this point, Supervisor Janice Hahn cut off the younger Lucas — who had reached the end of her allotted minute to speak — indicating that she, too, was off-topic.

“Okay, thank you, thank you,” Hahn said. “Again, I’ll just tell our speakers that we’re on the Community First Community Investment Spending Plan.”

Several subsequent speakers criticized the board’s treatment of the families.

Gabriella Vazquez of the JusticeLA Coalition thanked the families for spending the whole day waiting for a chance to speak to the supervisors about their lost loved ones. “I’m so sorry that the board has treated you so cruelly today,” Vasquez said.

Janet Asante, of the JusticeLA Coalition and Dignity and Power Now, said the county was failing the families of people dying inside LA’s jails at “every step along the way, including today.”

“We had families here today who took off work and flew across the country to speak to you all, and to be told — when your son isn’t even counted on the [death] tracker — ’let’s keep it to the subject of the motion,’” said Asante. “This is the subject of the motion.”

There’s a real disconnect, Asante said. “We’re trying to do this your way. We’re trying to do this through the bureaucracy that you have set up. We’re trying to do this very t and people are still dying, and that’s not on the agenda.”

Top photo by WitnessLA

Is there a credit for the photo of the jail at the header?

Editor’s Note:

Dear Noah,

The top black and white photo is by WitnessLA. I just now stuck in a a credit, which we unintentionally left off. Thanks for the reminder.

C.

Just wondering if Taylor has ever been in the “dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail”. I have – spent quite a bit of time there. It was built like jails were built back in the 60’s, much of it is linear style cell blocks, there are open dorms and a hospital and smaller lockups. I wouldn’t call any part of it a dungeon except perhaps the “hole”, where prisoners are housed for short periods in isolation for disciplinary reasons. I will admit there aren’t any windows as are present in today’s jails. One of the things, Taylor, you would be shocked at upon entry to the jail would be that,once you enter Main Control, and are actually inside security, you are walking among prisoners who are walking all over the jail. You will see, for the most part, they are not escorted. Is this normal in a dangerous, dungeon-like jail? Maybe in Taylor’s world. Yes, for the most part the prisoners are locked in cells once they return to their housing area (usually from visiting or the hospital) but there is no one with a whip or taser forcing them around like animals. All is pretty much calm, peaceful and relaxed for a dangerous and dungeon-like place.

In fact, Taylor, I would strongly urge you to leave puffy at home and go downtown and take a tour of the dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail. The Sheriff’s Department would be glad to let you go wherever you wanted (the would, of course provide you with an escort because it is such a dangerous place) and see for yourself. Oh, and by the way, I suppose you know there are watchdogs like the ACLU who have open and free access to the dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail 24/7. In fact, Taylor, are you aware that the ACLU have had to actually to rotate their watchdogs on a regular basis because after a few years of experience (and coming to realize the inmates tended to fabricate things to fit the ACLU’s agenda) inside the jail they realize that it isn’t what their superiors in the organization profess it to be. Two years was the life expectancy of these folks. The LASD got used to it. It might be an eye opener for you as well.

MCJ’s kinder face:

https://abc7.com/mens-central-jail-kids-library-childrens-gordon-philanthropies/13802174/

@media looks the other way I too have spent time in the Men’s Central Jail. By your description, you would make it sound like MCJ was a Marriot Hotel ” All is pretty much calm, peaceful and relaxed for a dangerous and dungeon-like place.” The dungeon like modules with limited access to fresh air or a “day room” or out of cell time can be considered “dungeon like.” Whatever time you spent in the jail, yup, there is daily movement, but what you failed to note is not all is calm and peaceful, especially when an inmate is beaten to a pulp in dorm or when an inmate is attacked in a court line cell. The list can go on.