I know I’m late to the party in commenting on the passings of Turkel and Hillerman, but, belated or not, I don’t want to let their exits from our temporal stage go unremarked here. (I am, of course, a lot later for George Orwell, who may seem like a confusing third party to include in this list, but I’ll get to my reasoning after the other two.)

*****************************************************************************************************************

STUDS TURKEL

Turkel was America’s oral historian—interviewing the celebrated and the noncelebrated with such deep compassion and inquisitiveness that it was as if he allowed his DNA and that of his subjects to briefly mingle. He was a die-hard, Depression-era leftist who was blacklisted during the McCarthy era, whose voice and manner always made him sound as if we was packing a weapon.

He was also one of the most truly, deeply American journalist/interviewer/writers this country has ever produced.

His deep curiosity drove him to try to answer over and over again through lens of hundreds of voices the most basic of human questions: “What is it like to be a certain kind of person, in a certain kind of circumstance, in a certain time? What was it like? What was it like?” What was it really like?

As Joan Didion wrote at the open of her famous essay The White Album, “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Studs Turkel’s great gift was to help hundreds and hundreds of Americans—famous and not– to tell their stories—and we are all of us the better for it.

“”I think it’s realistic to have hope,” he said in his later years to an NPR interviewer. “One can be a perverse idealist and say the easiest thing: ‘I despair. The world’s no good.’ That’s a perverse idealist. It’s practical to hope, because the hope is for us to survive as a human species. That’s very realistic.”

In the Chicago Tribune, Patrick Reardon, writes about how very, very much Studs mattered.

**************************************************************************************************************

TONY HILLERMAN

Like millions of others, I am a grateful Tony Hillerman fan. I read every single one of his mysteries set on the Navajo reservation and featuring Navajo tribal police officers Jim Chee and “the legendary” Joe Leaphorn. (To be honest, I read several of the books twice, as one revisits treasured and reassuring friends.)

Hillerman was the white guy novelist/outsider who wrote about Navajo rituals and traditions with a committment and respect that caused tribal elders and others to open up to him a way, in many cases, they did with nobody else. “The elders,” said Navaho “shaman” James Peshlakai, “they told him stories about things their own children never asked about.”

My wonderful writer friend, Samantha Dunn, who was an even more serious Hillerman fan than I, has said far better than I could, why Hillerman’s books are both joy-filled and, in their own ways, important.

***************************************************************************************************************

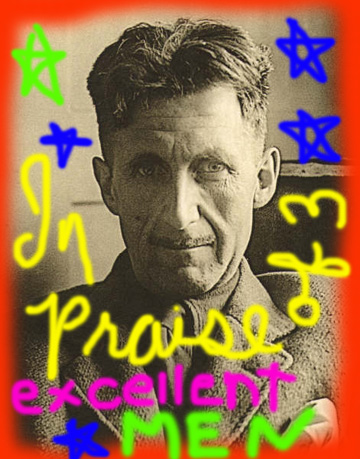

GEORGE ORWELL

Yes, yes, I do understand that George Orwell died some time ago (58 years ago, if you want to be picky), but there are two brand new collections of Orwell essays, edited by George Packer, that my brilliant pal, LA Times Book editor, David Ulin, tells us about in a short, but deliciously smart piece in today’s LA Times.

Like many of you reading this, for much of my life I was unfamiliar with Orwell except as the author of the two alarming futuristic novels that we all were made to read in middle or high school, 1984 and Animal Farm. David makes the point, and I agree, that, while essential reading, the two books for which Orwell was to be the most famous are, in many ways, the least significant—and, to be honest, the least interesting— of his works:

“Orwell’s legacy now seems shackled by those novels, his restless intellect reduced to slogans: “War is Peace; Freedom is Slavery; Ignorance is Strength,” “Big Brother is watching you.”

For Orwell, “Animal Farm” and “1984” were distillations; written late in his career, they represent a summing up. Far more fundamental is how he came to their perspective, how the worldview they portray arose.

It is his nonfiction—his essays and the three books most openly based on his personal experiences—-Down and Out in Paris and London, The Road to Wigan Pier, and Homage to Catalonia —-where one finds Orwell’s breathtaking mind the most engagingly at work.

I first came to Orwell’s nonfiction early this year when my newest advisor for my Bennington MFA program suggested that I read The Road to Wigan Pier.

I was at first irritated to be saddled with what I judged to be a book-length polemic. But when I grudgingly began reading, instead I found myself in the company of one of the best social thinkers of the 20th century who also happened to be a master of observation, a sly humorist, and a great and skillful storyteller.

I’ve been maniacally reading Orwell ever since. (And, as David observes, reading Orwell has seemed somehow exactly the right—and strangely comforting—thing to do during this wild and wooly election season.)

“I want George Orwell as my friend, and I hate it that he’s dead so I can’t talk to him,” I said to Ulin at a party last week, when we were discussing our mutual love for the man’s nonfiction. “I understand,” said David. “But latel I don’t just want to talk to him, I want to be him.”

(Me too. Except that I don’t think I’d look as good as David might in Orwell’s mustache.)

But if I could write with one twentieth of George Orwell’s keenness of observation and rigorous clarity of thought, I’d be one very happy gal.

If Obama is elected, Orwell’s timing would only be off by twenty-five years.