By Teresa Wiltz, Stateline

Babies and toddlers are entering the foster care system at a higher rate, a trend that some child welfare experts fear is correlated to the opioid and methamphetamine epidemics wreaking havoc across the country. And that is further straining the nation’s already overburdened child welfare system.

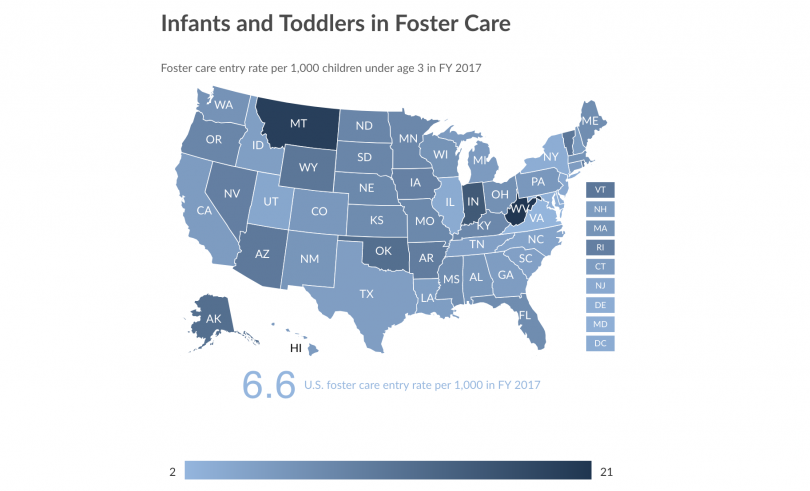

From 2009 to 2017, the rate of very young children entering foster care grew incrementally, exceeding the rates of older children, which remained steady, according to data compiled by Child Trends, a Maryland-based research organization that focuses on child welfare issues. In fiscal year 2017, children age 3 and under entered foster care at a rate of 6.6 in 1,000, more than twice the 2.8 rate of children ages 4 to 17.

“Babies are driving that increase,” said Sarah Catherine Williams, one of the authors of the Child Trends study.

The trend has a big impact on states, whose budgets often already are overstretched responding to the drug crisis and other needs.

West Virginia has the highest rates of very young children entering foster care, at 20.8 in 1,000 — and it also has the highest overdose death rates in the country.

West Virginia is followed in the foster care rates by Montana (19.6), Indiana (15.7), Alaska (12.6) and Oklahoma (12.6).

Opioid deaths jumped 77% in Alaska between 2010 and 2017. Montana and Indiana, on the other hand, have grappled with an explosion in methamphetamine use.

In recent years, there’s been a decrease in the overall number of Oklahoma children entering foster care, according to Sherry Skinner, program administrator for Oklahoma’s KIDS, Technology and Governance Unit.

But at the same time, there’s been an increase in children under 3 entering the system, Skinner said. In 2018, two-thirds of children removed from their homes were under 5, she said.

The increase in very young children entering the system is a result of the state’s meth crisis, Skinner said.

To be sure, while there’s a strong correlation between the drug epidemic and the increase in children entering foster care, there’s no data yet showing that it’s the direct cause of the uptick, child welfare experts say.

For example, Ohio, which ranks second in overdose death rates at 46.3 in 100,000, has a relatively low rate of babies and toddlers entering foster care.

But nationally, neglect and parental drug abuse are the most commonly reported reasons for removing children of all ages from their homes, according to Child Trends.

And more state child welfare agencies are saying they’re seeing an increase in children affected by the drug crisis, said Tracey Feild of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a Baltimore-based child welfare research and advocacy group.

Officials in West Virginia’s Department of Health and Human Resources declined requests for a telephone interview. Officials in Alaska, Arkansas, Indiana and Montana did not respond to interview requests.

On the other end of the scale, Puerto Rico (0.9), Virginia (2.2), Maryland (3.0), Delaware (3.3), and New York (3.3) had the lowest rates of young children entering foster care.

The different rates among states of children entering foster care in part are caused in part by highly variable state policies and procedures for removing children from their homes, said Jill Berrick, a professor at the School of Social Welfare at the University of California at Berkeley.

That’s because the federal government gives states tremendous latitude to customize their child welfare systems, Berrick said. This means that states differ considerably on who they require to report suspected child abuse or neglect and on in-utero drug use policies.

For example, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based reproductive rights advocacy group, fewer than half of all states consider substance abuse while pregnant to be child abuse under child welfare statutes.

Some states may be better at identifying babies at risk, Feild said, and in other instances, high-profile news stories about abused children have raised awareness, so more people may be calling local child agencies with concerns about potential maltreatment.

States also vary drastically when it comes to determining whether to take children from their parents. A 2017 Cornell University study found that states with more punitive criminal justice systems and restrictive public welfare benefits tend to remove children from their homes far more frequently than those with “generous and inclusive welfare systems.”

Often placing infants with foster families can be hard, because many foster parents work outside the home, which means they need to use daycare, said Irene Clements, executive director of the National Foster Parent Association, a Texas-based nonprofit. That can result in a shortage of foster families willing to take on an infant.

By the Numbers

Nationally, the number of children entering foster care increased every year from 2013 to 2016, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. At the same time, at least half of states saw a decrease in the number of available foster homes, according to a 2017 investigative project by the Chronicle of Social Change.

The numbers are troubling, because those early years are a pivotal time in child development, child welfare experts say. Abuse and neglect during this time has lasting effects into adulthood, even changing brain functioning. And children who enter foster care once are much more likely to be involved in foster care later in life, Williams said. Child welfare experts agree that children fare best in a family setting.

The number of babies entering the child welfare system likely will continue to rise until states are able to contain the opioid and methamphetamine crisis, child welfare experts say.

The federal 2018 Family First Act, which mandated a massive overhaul of the foster care system, further complicates matters, child welfare workers say. That’s because the law, the most extensive reboot of the child welfare system in nearly 40 years, prioritizes keeping families together and puts more money into at-home parenting classes, mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment.

But not all states are prepared to provide the level of care needed to keep families together, child welfare experts say. (Family First dictates that states get these programs up and running by October.)

For example, in Nevada, when an older child is identified as being at risk for abuse or neglect, her parents are connected to services such as substance abuse treatment that might help keep the family together, said Denise Tanata, executive director of the Children’s Advocacy Alliance, a community-based advocacy group based out of Las Vegas.

But in the state, children under 5 are considered a special, high-risk category requiring additional and immediate safety protections, so families with very young children wouldn’t qualify for those programs, Tanata said.

That means very young children end up in foster care to better protect them, Tanata said. Biological parents, meanwhile, could wait 12 to 18 months in Nevada to get into a substance abuse treatment program, she said.

Meanwhile, “you’ve put a child in a [foster] home where they’ve established a bond. Then you’re looking at the best interests of a child,” Tanata said. “They’ve been in this [foster] home, does it make sense to return them to their [biological parents] down the road?”

Babies who have been exposed to drugs pose even more challenges for foster families. Often they have a host of medical problems, including neurological issues and skin sensitivity, making it all but impossible to cuddle them, Clements said. And it’s tough to find a daycare center that’s able to meet their considerable needs, she said.

“When you have a baby that doesn’t feed well, cries a lot, maybe is experiencing apnea episodes, just all of it, becomes a full-time job,” Clements said.

Image by Pew Charitable Trusts: In fiscal year 2017, infants and toddlers under the age of 3 entered foster care at a rate of 6.6 per 1,000, more than twice the 2.8 rate of children ages 4 to 17.

Image Source: Child Trends, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System at the U.S. Children’s Bureau.

Teresa Wiltz is a staff writer for the Pew Charitable Trust’s Stateline, where this story first appeared.