The Journey of a Girl Gang Member Turned Justice Activist and Leader

as told to Celeste Fremon

Editor’s Note: The Open Society Foundation has named its 2017 Soros Justice Fellows. And one of the people that Soros featured the most prominently in their announcement of the foundation’s new selections is Claudia Gonzalez, a 31-year-old, former gang member living in Winton, California, who, for the last decade, has been struggling with a ferocious case of PTSD.

The Soros Justice Fellowship is arguably the most prestigious award of its kind in the nation. This year the 16 adults who were chosen for the honor are a mix of attorneys, advocates, artists, writers, researchers, and scholars, all of whom will receive stipends ranging from $40,000 to $110,000 for full-time projects lasting between 12 and 18 months. To apply for the fellowship, one must propose a project that, in an innovative way, will “push for progress toward a more humane criminal justice system in the United States.”

Gonzalez’ proposed fellowship project is a much-needed women’s prison reentry program that aims to help formerly incarcerated women in California’s Central Valley “find success and healing beyond the prison’s walls.” She feels very ready to take it on, Gonzalez told us. She has a strong background in activism, organizing, and in helping others to find the best in themselves.

Perhaps even more importantly, Gonzalez has a bone deep understanding of the kind of trauma that brings many women to the justice system in the first place. She also has a lot of hard fought knowledge about how to heal the resultant emotional wounds.

Here’s what she told us.

Gangs in the Family

Claudia Gonzalez saw her first murder up close when she was not yet a teenager. She began her life with her family in the Boyle Heights area of East Los Angeles where, by default, she grew up on the neighborhood streets.

Gonzalez’ father was in a street gang, and he went to prison when she was young. “He’s been locked up most of my life,” she said. Eventually, her brother would be locked up too, having followed a similar path. But that had yet to happen. “Gang membership is generational in my family,” said Gonzalez.

Gonzalez’s mother tried hard to keep an eye on her daughter, but she was working three jobs—cleaning houses, working in a fast food restaurant. On the weekend, she worked a variety of third jobs. By the time the mom got home, she had time for little but sleep. “As an adult, I understand what she was dealing with,” Gonzalez told WitnessLA. “But when I was little, it left me really vulnerable. We were at the margins are already. So I was always in the neighborhood.”

During much of the 1990’s, hanging around on the streets in certain violence-haunted California communities meant that even kids who weren’t involved with gangs at all risked being perceived as being gang associated by the police and by other gangsters, simply based on where they lived. In Gonzalez’ case, the family legacy exacerbated the perception.

Thus when Sanchez and her young friend, a handsome boy with humor in his face whom she’d known for most of her life, simply walked to the corner store for a cold drink or a snack, it meant possibly being confronted by “enemies.”

One day that’s exactly what happened.

He died in my arms on the way to the hospital

“We ran into a rival gang at a 7-11,” said Gonzalez. Words were exchanged, and a fight broke out between her friend and the “enemy” boys. “One of them pulled out a knife and he basically gutted my friend. He died in my arms on the way to the hospital,” she said. “In the ambulance. I was trying to hold in his intestines.”

She was 12-years old.

In the next nine years, there would be other deaths of other close friends, but this first terrible murder sent Gonzalez into dark emotional waters, and she began spending more and more time on the street. Her frantic mother moved the family to San Jose, California, hoping to get away from the danger. But the move only meant the names of the gangs and the “enemies” changed.

The School to Gang to Prison Pipeline

In San Jose, Gonzalez’ father was still in prison, and her mother was still largely unavailable. Then her gang member brother went to prison too, with a murder conviction. Although she was a smart kid and had been a good student, now Gonzalez was struggling to focus, and she began cutting classes.

“So much was happening to me personally,” she said. “I just didn’t want to be in school.” At her middle school, instead of asking the smart, unhappy girl what was going on in her life, or calling her mom to alert her that there was trouble, Claudia said the school officials simply punished her. When the truancy continued, a school resource officer threatened her with criminal charges. “He told me ‘the next time I see you cutting, I’m going to take you to jail.”

According to Gonzalez, the officer made good on the threat and, the next time she cut class, he arrested her in a highly public action. “It was in front of everybody at school. I felt like I had committed this horrible crime.” Gonzalez was taken to San Jose’s juvenile hall and booked for truancy.

I remember I believed that was some kind of point of no return…

With no one seemingly able to reach out to her, calm her fears, and help her get back on track, Gonzalez saw the arrest as outsized and ruinous.

“I remember I believed that was some kind of point of no return. I felt like there was no future for a girl like me.”

When she was released, a humiliated Sanchez found that her arrest had indeed set her uncomfortably apart from her classmates. In the neighborhood, however, the time in juvenile hall gave her “street cred.”

“I was one of the only girls anybody knew who’d gone to juvenile hall.” And as devastating as it was for her that her gang member was in prison—likely forever–that fact too gave her status.

My new dream was to steal a cop car

Gonzalez made up her mind to become a gang member, the role she now figured was the only thing she had a talent for. “My new dream was to steal a cop car, lead the police on a chase, and then get caught and go to prison.”

A Girl in a Boys’ World

Gonzalez was 14-years-old when she was officially “courted-in” to one of the Surenos gangs of San Jose, one of only two girls in an all male gang. But unlike the other girl, whom Gonzalez said eventually quit to start a family, Gonzalez was determined to be really, really good at being a gang member. She developed a bring-it-on attitude to defend against her fear and trauma. She even welcomed the traditional male initiation, in which she was beat-down like the boys by a group of young men who hit her hard.

During the next 7 years, she would be in and out of first juvenile facilities, and then adult lock-ups.

Interestingly, rather than attempting to discourage her from attending school, her fellow gangsters encouraged her to go back. “You’re smart,” they kept telling her. “You should be in school. That’s the place for you.”

For years she didn’t listen. She did, however, keep reading. And she watched the news. She wanted to keep up with what was going on in the world and with her community. “I became like the ‘hood lawyer,” she said. “I was the person that was always able to figure things out for the other homies. And this is like pre-internet.” It was also during her gang years that she first realized her she had a talent for leadership.

Yet Gang life inevitably produced additional trauma for Gonzalez, as research has shown it does for most adolescents and young adults who have grown up in and around the gang world, where the exposure to death and violence was often similar, statistically, to that experienced by service men and women who served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

I thought, well, maybe there is something else for me

One year in particular, when she was around 20 years old, Sanchez had five close friends killed. “Not people I just know. Close friends,” she said. “I started thinking about, well this is going to be my life; I’m going to end up either dead or incarcerated.” Yet her grief was intense enough that it began to pierce the protective shield of fatalism that had characterized her teenage years. For the first time, Gonzalez began to wonder if there was another way to think about her future.

“I thought, well, maybe there is something else for me.”

Getting Out

Around that same time Gonzalez’ mother, who had by then remarried, moved away from San Jose to the Central Valley, where she and her husband found they could more easily afford to buy a home. They invited Gonzalez to go with them. Seeing the move as a way out, she accepted the invitation.

But breaking free from gang life turned out not to be as easy as she had hoped. People the Central Valley had heard of her, and they invited her to parties, treating her as if she had a sort of street-bred celebrity status. Since she had few friends in the new area, the attention was flattering.

But one night Gonzalez was in a car coming from some party or other when she and her companions were pulled over and arrested. In a case of mistaken identity, she found herself charged with committing a crime she knew nothing about. Reverting to her old gang code, she refused to try to defend or explain herself. Gonzalez refused all offers of deals and instead told her attorney she would go to trial, which meant staying in jail for many long months while she waited for the wheels of justice to grind slowly.

I thought I was dreaming. I thought the COs [custody assistants] were playing a trick on me.

During that time, her devastated mother came to visit her, and her mother’s obvious grief had a shattering effect on Gonzalez. She promised herself that if she ever got out of this legal mess she would go to school, whatever it took, as a way of trying to repay her mother for all the years of worry and heartache.

Yet, before she actually made it to trial, a legal miracle occurred. Still looking for others involved in Gonzalez’ case, the police arrested one of the real perpetrators, who quickly made a deal and gave the cops everyone else, together with every detail of what had occurred. In doing so, the real participant inadvertently cleared Gonzalez.

The charges against her were dropped and she was released one day in the middle of the morning. “I thought I was dreaming. I thought the COs [custody assistants] were playing a trick on me.”

But they weren’t and suddenly, for real, she was out.

From Best Gangster to Best Student

Gonzalez had already taken the necessary test to get her GED while she was locked up. So when she was released from jail, to keep her promise to her mother and herself, she signed up for a local adult ed school where she quickly completed the school’s office technology program.

The office technology class was a six-month program. “And I completed it in one month,” said Gonzalez who also said that the adult ed people told her that “no one in the history of the program had every done such a thing.” They also told her she belonged in college and helped her with registration and enrollment in two-year Merced College.

I told my professors that I’d just gotten out of jail

At Merced, according to Gonzalez, she realized right away that she was totally unprepared to succeed in any kind of genuine academic environment. So she leveled with her teachers. “I told my professors that I’d just gotten out of jail. And I wanted to change my life. But that I didn’t know what I was doing. So could they help me?”

Her teachers were happy to help. Once given some encouragement, and a bit of catch-up tutorial, Gonzalez quickly took to academics, and got a 4.0 her first semester. “And that opened a lot of doors.” By the end of year one, she was in the honor society roll, and student government. In 2011, she was student of the year.

As she had with the office course, Gonzalez sped through Merced by being at school, including her work study program, from 8 a.m. until around 10 p.m. at night.

They said ‘You need to dream bigger’

As graduation approached, she wondered if she could take the next step and get into a four-year school. Her dream school, she said, was San Jose State. But when she talked to her advisors and professors, they discouraged her from applying to San Jose. “They said, ‘you need to dream bigger.’”

So she did. Gonzalez applied to a pile of Universities of California. She got into UC Berkeley, where she got a full ride and was a Regent’s and Chancellor’s Scholar. There she majored in social welfare, and worked with the school’s Teach in Prison program, training other students to tutor people incarcerated at San Quentin.

But, as well as she was doing at U.C. Berkeley, there was a problem.

Trauma Rises

For one thing, Gonzalez quickly developed the “imposter syndrome.”

“I didn’t see people at Berkeley like me, so I felt like they’d made a mistake letting me in, that I shouldn’t be there. I was an impostor.” So, although she did well in her school work, she struggled emotionally—until a professor introduced her to some other bright students who had similar histories, and who were forming a group called Underground Scholars. In their company, her imposter feelings pretty much vanished.

But then there was the trauma.

Prior to Berkley, she’d managed to cover her unresolved emotional wounds with activity. “I kept myself busy, trying to be best gang member I could be. Then trying to survive in jail Then getting out and trying to survive on the streets again.” And then racing through Merced College, and so on.

“There was no time to cope, no time to breathe. It wasn’t until I got to Berkeley and I had… free time.”

Then to make matters worse, her first semester she was robbed at gunpoint. “All my life I’d had guns pulled on me,” she said. But, now she cared about her life, and this time felt different. “It was two guys and I’d already given them everything I had,” she explained. “I gave them my wallet, which only had ten dollars in it.”

…he put his gun right on my forehead

She assumed they would take her things and leave. “But I guess I didn’t react the way they expected it. I didn’t scream or cry.” So the one guy began trying to frighten her. “The other guy got nervous and kept saying, ‘Let’s go. We got the bag.’ But the first guy wouldn’t leave.” He wanted something more from her, in attitude, she said. “So he put his gun right on my forehead pretended that he was going to shoot me. So that really got to me.”

With the extra blow of the robbery, the various traumas of her life flooded into her consciousness with extreme force, and Gonzalez began having panic attacks. She went to a therapist who diagnosed her as having Post Traumatic Stress Disorder—PTSD

During therapy, she began to talk for the first time about the painful events of her childhood, adolescence and young adulthood. She fell into depression, and her schoolwork suffered.

After a year plus of struggling, eighteen units short of graduation, Gonzalez understood she needed to take a break.

“I realized it during my last final,” she said. “I was always the first person in the room finish. But at that last final it took me three and a half hours to complete the test. Whereas before it would often take me a half hour.” She concluded that if she didn’t asked for permission to put her schooling on hold, she would start failing classes.

So she requested the needed break, and moved home.

There were days I didn’t want to live

It was a very difficult period, she said. Her family didn’t know what to do to help her. “My mom thought there was something physically wrong with me, because I slept all the time.

“There were days I didn’t want to live.”

Working to Heal

Yet, despite her inner turmoil, Gonzalez got work as an activist and an organizer. Among other positions, she worked for Pico California, a community-based organization that recruited her to work on the passage of Proposition 47, which was designed to reduce certain low-level felonies to misdemeanors. “The organizers felt that if it didn’t pass in the Central Valley, it wouldn’t pass in the state,” she said.

After that, she began working with kids, which led to her to become the program manager for an innovative youth program called We’Ced Youth Media (which we profiled last month).

I would never be an effective leader if I didn’t deal with my own trauma.

At the same time, she did her best to begin to heal herself.

‘I realized I would never be an effective leader if I didn’t deal with my own trauma.”

Gonzalez turned a corner when she met a marriage and family therapist with whom she clicked during her advocacy work, and the MFT began working with her unofficially, helping Gonzolez help herself so that she could help the young women and men she was working with.

The process of opening up to someone she truly trusted made a crucial difference. Addressing her past was still hard, but it no longer felt impossible, she said.

It was this same mentor/therapist who encouraged her to apply to Soros.

“I knew what I really wanted to do was to help incarcerated women and recently incarcerated women in the Central Valley.” It is a project that feels like a calling, she said.

Now her goal is twofold: Once she finishes her eighteen-month Soros commitment, and has her women’s reentry program up and running, she intends to go back to Berkeley and finish up those last 18 units.

“It would be the biggest reward for my mother to see me graduate.”

But she does not intend to let go of her project that will offer wrap-around aid to incarcerated women. “It’s my life’s work,” she said. The project includes the impact of incarceration on kids because, she said, “I want to help them so they don’t have to go through what I went through.”

“So, yeah, I’m doing a lot right now,” she said after a breath. “And I’ve got a long way to go. But I’m really motivated.”

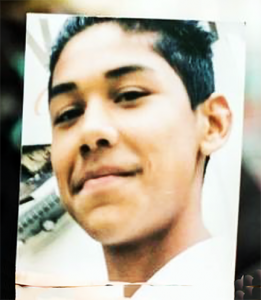

Photo courtesy of the Soros Foundation.