In a new report, the non-profit Impact Justice explored the effects of a program in Alameda County that employs restorative justice techniques to keep juveniles out of lockup.

Community Works West’s Restorative Community Conferencing (RCC) program diverts more than 100 young people away from the juvenile justice system each year, according to the report. The program brings the youth—supported by their family and community—face to face with their crime victims to engage in a dialogue to repair the harm done.

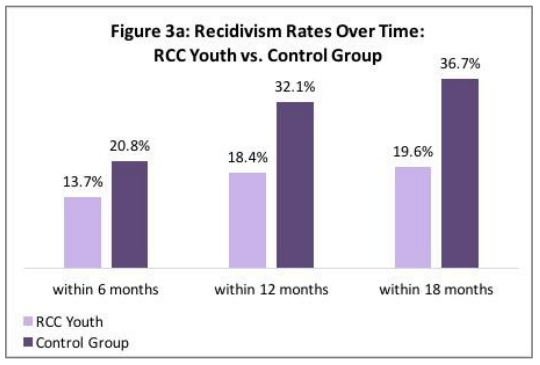

The report looks specifically at three years’ worth of data from January 2012 through December 2014, comparing outcomes between kids who graduated from the RCC program and a control group of kids whose cases were processed in the juvenile court system.

Within the first 12 months of graduating from the program, kids were 48% less likely to commit another offense than their peers whose cases were handled in court.

Out of a pool of 103 kids that participated in the program between 2012-2014, after one year, only 18.4% were found to have committed another “delinquent” act. (Just 13.7% had committed another offense within 6 months, and only 19.6% within 18 months.)

In comparison, the kids whose cases went through Alameda County’s court system had a reoffense rate of 20.8% within 6 months, 32.1% within 12 months, and 36.7% within 18 months.

RCC was fashioned after a New Zealand program, Family Group Conferencing, which was launched in 1988, and according to the report, “has rendered youth incarceration nearly obsolete in New Zealand.”

While some alternative court programs require individuals to plead guilty in order take advantage of the program’s services, the RCC program gets kids before a prosecutor files criminal charges.

The Alameda District Attorney has full discretion regarding which cases to send to RCC. The program selects cases that involve serious crimes (like robbery, auto theft, assault, and arson) that have a specific identifiable victim, and for which kids would face considerable juvenile justice system contact.

The program provides surveys given immediately after the conference takes place.

“When an offense occurs, legal proceedings can often be intensive, traumatic, and time-consuming for the responsible party, the person harmed, and their families and community members,” the authors wrote in their report.

Most victims found the process to be meaningful to them. Eighty-eight percent said the meeting addressed the offense’s personal impact. Three-fourths of respondents said the process had either a “good” or “big positive” impact on their relationship with their loved ones. And 84% saw a “good” or “big positive” improvement in their ability to handle conflict. Seventy-five percent said their communication skills improved following the conference. Eighty-two percent indicated that they have employed restorative justice practices like truth-telling and repairing harm on their own since the conference.

Of the youth who responded to the survey, 92% said that “having support” was either “important” or “very important” during the proceedings, and 90% said “having a voice” was crucial. Nearly all—99%—said it was helpful to speak directly to the victim.

Many parents surveyed following the conference said aspects of their children’s lives improved, including their behavior, relationships, communication, and grades. One parent said the conference was “a great opportunity for honest conversation and communication” that served to “deepen understanding of impact,” and was a “more developmental option than incarceration.” Another parent said the process gave her son the opportunity to “step up and take the responsibility for his actions,” which “made him feel good about himself.”

“I absolutely believe that this is a better alternative for young [people], their families, and even the victims of crime,” one parent said. “In this program, the young person is confronted with the seriousness of his crime and the harm it caused.” The youth “is given the chance to do something to make up for his crime and to apologize directly,” the parent said. “This is so much better than going through the legal system in which the main object is for the culprit to protect himself by hiding details of what he did, if necessary.” And, regular “restitution is impersonal,” the parent added.

The program, which receives funding from the US Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) has an average one-time cost of $4,500, compared with $23,000 per year on average for a juvenile on probation—not including other legal costs to the public defender’s office, district attorney’s office, court costs, and more.

The RCC process, the report says, also relieves some of the pressure on overburdened courts and probation departments.

The report also compared RCC with another of Community Works’ programs, one called, “Make It Right” in San Francisco, initiated by San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón.

Make It Right serves a quarter of the number of defendants that RCC does, and only youth accused of felony offenses. There is also no discretion on which cases ultimately go to Make It Right. According to the report, “the Managing DA of the Juvenile Division makes a charging determination on felony cases eligible for Make it Right, and then uses a randomization process to divert 70% of those cases to Make it Right pre-charge.”

However, Make It Right, which is funded with county money, has a considerably lower recidivism rate than Alameda’s RCC. One year after completion of the restorative justice process, just 5% of Make It Right participants are found to have committed another offense.

There are several possible reasons that the programs have different outcomes. Research has shown that low-risk juveniles, like the ones served by RCC, have better outcomes when there are no interventions. Other studies show that restorative justice has a bigger positive impact on individuals who have committed more serious crimes. The report suggests that, considering the two programs are run by the same provider, additional research into the significant disparity would be worthwhile.

Alameda and San Francisco aren’t the only California jurisdictions with successful youth diversion programs. In Los Angeles, Centinela Youth Services (CYS) and the LAPD have partnered on an unusually effective diversion program for lawbreaking youth called the Juvenile Arrest Diversion Program. (Read more about it: here.)