The consistent decline in juvenile crime, along with study after study showing that many kids do far better in community-based programs rather than in county lock-ups, has led to a large drop in population in LA County’s juvenile halls and camps, along with a significant downturn in the number of youth on court-ordered probation.

There is, however, one youth program run by Los Angeles County Probation Department, the population of which is radically on the rise.

It is a school-based program that is informally known as voluntary probation, and it has flown largely under the radar.

In the story below, reporter Jeremy Loudenback, the Child Trauma Editor for The Chronicle of Social Change, examines this little-known but heavily funded LA County Probation strategy that some child advocates say is a misuse of millions of dollars in state funds, which would be better allocated to community intervention programs with data-backed ability to help kids stay out of the justice system.

Instead, say youth advocates, kids in need of tutoring, mentoring, counseling, sports programs, and other kinds of positive activities and alternatives that are known to help adolescents steer their lives in a healthy direction, are—for all intents and purposes—on probation, reporting to probation officers side-by-side with other probation kids, except without a judicial order.

“Most of these kids think they really are on probation,” a source familiar with the program told us. “And their friends think they’re on probation too.”

Also of concern is the fact that the money to pay for this so-called voluntary probation comes out of the approximately $31 million that LA County receives yearly from the state that is specifically designated for local programs aimed at keeping kids who’ve tangled with the juvenile justice system from returning, and to help kids at risk of winding up in the system from entering it in the first place.

Yet, the largest chunk of that $31 million is not paying for juvenile programing that has been proven to produce measurably positive outcomes. According to probation department documents that WitnessLA has obtained, the biggest piece of the monetary pie is going to help to pay the salaries and benefits for the county’s juvenile probation officers—salaries that are reportedly meant to be paid out of other pockets of Probation’s $830 million yearly budget.

WitnessLA will have more on this issue in the coming months. But Loudenback’s excellent report below is the essential place to start.

This is also, by the way, one of a number of important juvenile justice issues that we hope the new, soon-to-be-selected Chief of Los Angeles County Probation will explore with a critical eye.

So get comfortable, and start reading.

THE RISE OF VOLUNTARY PROBATION FOR LA COUNTY YOUTH

by Jeremy Loudenback

While Los Angeles County has seen a historic decline of the number of youth in its juvenile camps and halls in recent years, a “voluntary probation” program run by the Los Angeles County Probation Department has dramatically expanded during that time, alarming some advocates.

The arrangement allows probation officers to work with at-risk youth in schools with no prior history of involvement with the justice system, as long as their families sign off.

There are nearly 3,600 youth on voluntary probation, according to a data snapshot recently provided by the Probation Department.

According to RAND data released last month, the number of youth on voluntary probation has grown by nearly 40 percent over the past two years. And since 2013-2014, the number of youth on voluntary probation in the school-based supervision program has exceeded the number of youngsters in the program who have been arrested and are on formal probation.

PROBATION OFFICERS AS TUTORS

The spike has prompted advocates to question why probation officers are now so often a part of the lives of youth with academic problems, and what the role of probation should be.

“Even if a young person needs tutoring, we should be asking whether a probation officer providing or doing the referral for tutoring is really what we should be asking probation officers to do,” said Patricia Soung, a senior staff attorney with the Children’s Defense Fund-California. “This is a significant shift in population, and it’s not apparent to me that there’s been a corresponding change on the department’s side to accommodate the new demographics.”

At an April meeting of the county’s children commission, the Probation Department first released preliminary data about these youngsters, known as “236 youth” because of the state statute that allows the Probation Department to work with them.

That law — known as Welfare and Institutions Code 236 — allows probation departments in California to “engage in activities designed to prevent juvenile delinquency.” The law permits probation officers to provide services to any youth in the community, not just those being supervised by a probation officer as part of a court order.

The money that funds the school-based supervision program is allocated from the Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act (JJCPA). In 2001, the state started doling out $100 million a year in JJCPA money to counties for prevention and intervention services aimed at young people.

Los Angeles County’s share last year came to about $30 million, and the Probation Department has invested a substantial portion of those funds for its work in schools. More than 100 deputy probation officers have been installed at schools across the county, including at 58 middle and high schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Youth who are on voluntary probation — the so-called 236 youth — check in with officers at school, alongside youth who are in the system already, as part of court-ordered probation because of an arrest.

Youth can only be placed on voluntary probation with the consent of a parent, who must sign a waiver and contract.

Of the 3,590 youth on voluntary probation in L.A. County in March, more than 80 percent were referred to the school-based supervision program for school-related issues such as poor school attendance, grades or behavior.

“If we know that almost 80 percent of reasons for referral are something related to attendance, grades or school behavior-related, then I really question whether probation case management is what that young person really needs versus school intervention,” Soung said. “The practice is counter to research that shows probation supervision should really focus on high-risk, high-need youth.”

The remaining 20 percent were referred to the program for being unmotivated, having anger issues, substance abuse problems and parental conflict, among other challenges.

While at school, the 236 youth receive many services not usually associated with probation. Nearly 31 percent — or 1,106 youth — received tutoring services from probation officers. About 18 percent received gang prevention services, while 11 percent were able to access family counseling.

Probation Department Deputy Chief Felicia Cotton says that the school-based supervision program is a purely preventative effort that doesn’t cause youth to end up in the system. Voluntary probation, she says, is an important tool that the department can offer parents who fear their wayward children are on the brink of getting into real trouble.

“A lot of parents come to us because they see their kid on the verge of hanging out with the wrong crowd, flirting with gang activity, not going school,” Cotton said. “The parent doesn’t know what to do. They’re afraid. They come to us.”

Cotton says that the program has made the on-campus probation officers a “hot commodity” with school officials, who see it as a valuable resource to address truancy and other school-related issues.

Because data about 236 youth is not logged into the probation department’s case-management system, the increased number of youth on voluntary probation has escaped notice from some in the county’s juvenile justice community. More important, the lack of data around these youth has made it difficult to evaluate whether it has been successful in preventing at-risk youth from becoming more entangled in the county’s sprawling juvenile-justice system.

“If probation is going to focus time, effort and resources on a 236 population, then it is incumbent upon them to evaluate the impact of that,” said Denise Herz, a California State University, Los Angeles researcher who has studied outcomes for young people in the county’s juvenile justice system. “They’re not doing that and they should.”

PROBATION PIVOTS AS CASELOADS DECLINE

Beyond these concerns about data, the department’s investment in school-based supervision raises larger questions about the role of probation during a time of significant demographic change, an issue that other counties across the state are also grappling with.

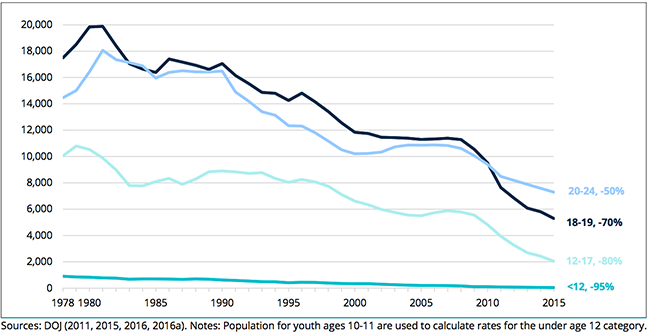

Youth arrest rates have plummeted in California since the mid-1990s. Juvenile arrests for violent offenses declined by 70 percent across the state from 1995 to 2015, according to the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

In Los Angeles County, the juvenile arrest rate in Los Angeles County has dropped by 60 percent from 2010 to 2014, and 30 percent since 2012.

Over that time, the Probation Department has also seen a stark decline in the population of youth at camps and halls. The average daily population of its 13 juvenile camps is 600, with 700 youth in juvenile halls and approximately 10,400 youth under supervision. This is a far cry from more than a decade ago, when more than 30,000 youth were on probation and 4,000 youth cycled through the county’s detention facilities.

With L.A. county currently searching for a new probation chief and hoping to implement a therapeutic approach at its still-troubled juvenile halls, the department’s shift to voluntary probation is leading some to question how probation services should best be deployed, both in L.A. and across the state.

As probation departments manage smaller caseloads, will they re-invent themselves into different functions — such as case management for community-based services — that have more in common with social services than public safety?

For now, Probation Commissioner Cyn Yamashiro hopes the department will share more information at a probation commission meeting in October to address lingering concerns.

“If the supervision is a tool that is being used to effectively prevent penetration into the juvenile justice system, that’s important,” Yamashiro said. “If on the other hand, the data reveals that it’s not helping to divert youth away from the juvenile justice system and it ends up a way to increase or capture more youth in the system, that’s something we want to know, too.”

Jeremy Loudenback is the Child Trauma Editor for the Chronicle of Social Change, where Loudenback’s story—and the accompanying graphics—originally appeared.

“If we know that almost 80 percent of reasons for referral are something related to attendance, grades or school behavior-related, then I really question whether probation case management is what that young person really needs versus school intervention,” Soung said. “The practice is counter to research that shows probation supervision should really focus on high-risk, high-need youth.”

-Which research is Soung citing? Does she even know what she’s talking about? Is she and the author simply trolling the side of the story that serves the self-anointed advocates position?