The highly controversial Los Angeles County Probation youth program known colloquially by critics as voluntary probation is now reportedly scheduled to be shut down—at least in part—by April 1 of this year, with the rest of the program likely to be shuttered by the end of the school year in June 2018.

Veteran youth advocates WitnessLA contacted expressed both relief and optimism at the news that the “probation lite” program, which puts at risk school children who’ve never broken the law under the supervision of probation officers, was looking as if it might be headed for the dustbin.

“I am excited that the new [probation] leadership is making long overdue changes that are in keeping with best practices, as well as research, regarding what makes sense for young people,” said Patricia Soung, Director of Youth Justice Policy at the Children’s Defense Fund–California. “The fact that youth as young as middle school are being introduced to probation officers without any court-ordered probation involvement is a poor allocation of resources and potentially harmful for the young people involved.”

Yet, many rank-and-file probation officers, along with their supervisors, feel that, to the contrary, doing away with what is technically known as the WIC 236 program (in reference to a section if the state’s California’s Welfare and Institutions Code), is a distressing mistake.

And both factions want to know what will be done with the healthy pile of state funding dollars that have been allocated to support the program, if it is indeed to be shut down.

So what is “voluntary probation” anyway?

For those unfamiliar with the program in question, and why it may be slated for closure, in brief, informal or voluntary probation involves children between the ages 10 and 17 who are flagged by their middle schools or high schools as “at risk.”

The flagged kids are, in turn, referred to a professional probation officer for case management and services—even though they have broken no laws and have no history of court or probation system contact. This is ostensibly done with their parent or guardian’s permission.

According to an April 2016 snapshot, nearly 85 percent of the youth who were on voluntary probation supervision during that period in LA County were referred for some kind of school-related issues such as poor attendance, sliding grades, behavior in class, or overall performance at school. Only a small percentage were referred for more serious or non-school reasons, like drug involvement, anger issues, or fighting with parents.

One of the fundamental problems with this method of working with at-risk youth, according to a comprehensive 2017 report, “WIC 236: ‘Pre-Probation’ Supervision of Youth of Color With No Prior Court or Probation Involvement,” is that both anecdotal information and an expanding body of research suggests that justice system contact (with probation, law enforcement, prosecutors and/or courts) by youth “can be ineffective at best, and harmful at worst.”

For instance, the report’s authors wrote, citing a 2009 study, “'[b]eing put on probation, which involves more contact with misbehaving peers, in counseling groups or even in waiting rooms at probation offices, raised teens’ odds of adult arrest by a factor of 14.’”

Matters were not helped, according to the report, that parents of the kids involved were often unaware that participation was discretionary, and the kids who are referred to the program very often feel that they have done something wrong, and conclude, as one girl put it, they are being branded as “a future criminal.”

In a 2016 snapshot, the authors reported, 1,106 of the voluntary probation kids—or 30.8 percent— were getting tutoring, which the authors saw as telling indicator. “Typically,” they wrote, “probation officers have neither the training nor expertise to effectively work with youth struggling with academic or behavioral issues.”

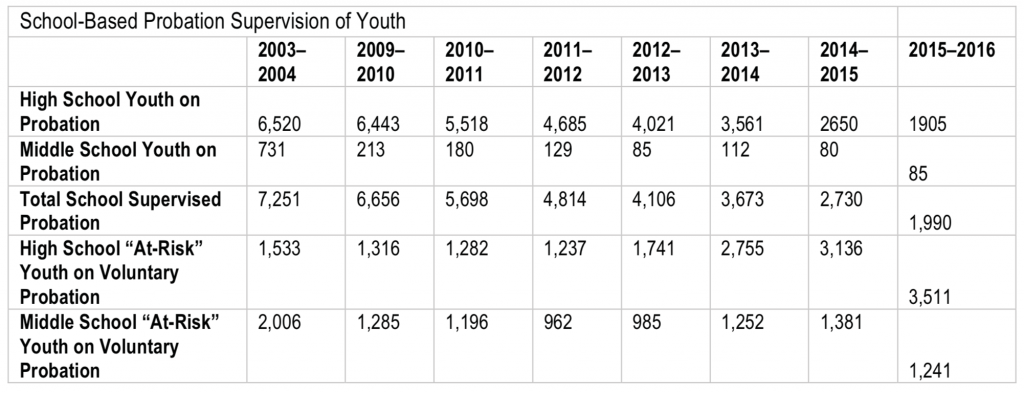

As juvenile crime continued to drop in LA County, for the 15-16 school year, there were more than double the kids in voluntary probation than on formal probation

(Last year, WitnessLA reported extensively on the 2017 report and county’s voluntary probation strategy.)

The law and the money

Legally, the program is authorized by California’s Welfare and Institutions Code section 236 (WIC 236), which is a statute that grants probation departments across the state the authority to intervene, through direct or indirect services, in the lives of any young person, including those who have not been accused of violating the law.

With such kids in mind, in 2000, the California legislature passed the Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act (JJCPA), which in turn caused the state to start setting aside millions of dollars a year for kids who were struggling with “delinquency.”

The main source of income for this stream of money is the state’s vehicle license fees.

The approximately $30 plus million that LA County receives yearly from JJCPA is specifically designated for local community-based programs aimed at keeping kids who have tangled with the juvenile justice system from returning, and to help kids at risk of landing in the system from entering it at all.

(And if the juvenile justice portions of Governor Jerry Brown’s budget gets through the legislature unscathed, LA County reportedly may soon be getting closer to $40 million per year.)

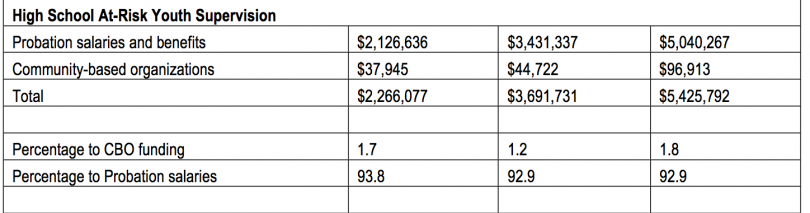

Under the regulations governing the JJCPA funding, only .5 percent of the pile of state dollars designated to help the WIC 236 kids is supposed to be spent on administrative costs such as paying probation officers salaries, which are supposed to be paid by the probation department’s own funding streams.

The main part of the JJCPA funding is supposed to go for community-based programs that have been proven to produce measurably positive outcomes for at-risk youth.

But, according to the 2017 report (and verified by internal probation documents), year after year, the biggest slice of the funding pie — approximately 90 percent — helped pay salaries and benefits for the county’s school-based juvenile probation officers, with a fraction of the funds left over to provide the much-needed programs for the kids being served.

Heirs to a pile of problems

The controversy over voluntary probation has been one on a long list of problems that LA County Probation Chief Terri McDonald, and her second in command on the juvenile side of the department, Sheila Mitchell, inherited last January from the previous crisis-fraught administration, and which McDonald and her upper management team have been working to sort out and fix.

In Los Angeles County, the WIC 236 youth program operates in many of the county’s public high schools and middle schools in the in 85 communities that are labeled by probation as the county’s “most crime-affected” neighborhoods.

It is the middle school part of the program that is scheduled to be shut down at the end of next month, according to a statement that Chief Deputy Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell made on Monday, February 5, when she spoke before the county’s Commission for Children and Families.

McDonald and Mitchell are expected to shut down the high school program by the end of the present school year, although they have also noted that many high school principles like the program.

Unions not thrilled

The two major unions associated with LA County Probation are unhappy with the scheduled shuttering of the middle-school program, and the likely closing of the high school program in June, and have approached the board of supervisors and others in the hope of getting someone to reverse the proposed closures.

“Sadly, many parents are not capable or are not motivated to help their children become successful in school,” wrote John Tuchek, in the January newsletter for SEIU 721, the Association of Probation Supervisors, about the proposed loss of the program. Tuchek is a veteran probation supervisor who is also the vice president of SEIU 721. “The DPOs see this daily and assist the parents with advice and referrals.”

The parents, he wrote, are also referred to parenting and other self-help programs.

“Most of the improvement is qualitative and is not seen in the empirical data because the case is closed and the students and parents are empowered to continue with their lives outside Juvenile Justice System,” Tuchek wrote.

When WitnessLA asked Sheila Mitchell about the two unions’ response to the planned closures, she was upbeat but firm.

“We are proud of the commitment and work that our staff engage in supporting at-risk youth in middle and high schools,” she emailed back. “However, as we look at our limited resources and how well we are doing meeting the supervision needs of our probation youth, we determined it is in the best interest for our staff to be redeployed to reduce caseloads to ensure we are successful in addressing the critical needs of youth on Probation.”

A report released in November 2017 that compared LA County Probation practices with “best practices in the field,” supported what Mitchell said.

“Youth should be diverted from formal processing to the greatest extent possible and similarly incentivized to excel on probation through grants of early discharge,” said the report, prepared by Resource Development, Associates. “These practices are consistent with evidence-based community corrections and help to reduce potential harms that come from supervising low-risk populations. Actively supervising fewer individuals helps conserve resources so that probation departments can implement innovative programs and have greater access to resources dedicated for higher-risk cases. Further, it is well-established in the research that supervising low-risk clients increases their risk of recidivism.”

Okay, so if Probation Lite goes away, what should come next to help LA County’s vulnerable kids?

The road ahead

Soung, who was one of the authors of the 2017 report on the program, said that any discussion about how the JJCPA resources should now be re-allocated requires strong community involvement.

“I think the next big question,” she said, “is how we ensure that what was intended by the JJCPA—-[namely] access to a mentor, case management, and services—is provided through another framework, through the schools and community-based partnerships.”

Julio Marcial, director of youth justice at the Liberty Hill Foundation, went further.

When it comes to its youth, he said, Los Angeles County is number one for all the wrong reasons. “We have the largest juvenile justice and child welfare system in the county. What we don’t have is the largest youth development system that helps young people change the odds, not just beat the odds.”

The projected closure of the voluntary probation programs represent “an opportune time,” Marcial continued, to begin to build such a system. “The number of young people being arrested is at an all-time low. The number of youth that are being incarcerated has declined by 70 percent.” Furthermore, he said, LA is closing at least one of its youth probation camps and repurposing it into a vocational education center, with plans to do more.

“So there’s an opportunity to use existing public dollars that should be directed to community-based, owned, and operated organizations and other non-law enforcement public agencies to work with young people and families to keep them out of these systems that many people have said are harmful to their development.” But the county cannot forget about those young people that are already involved in those systems, he said.

“The pendulum needs to swing toward developing a robust youth development system that does not currently exist,” according to Marcial. Yet, he points to other municipalities—like San Francisco, and King County, Washington—that have already begun programs of this nature.

“This is a perfect opportunity to reassess our priorities in how we treat young people” and to ask how we “ensure that all our young people succeed, learn, and thrive.”

Post Script: following the money

WitnessLA reported more than two years ago as part of our Follow the Money series, about how the county’s Juvenile Justice Coordinating Council (or JJCC), the body that decides how LA’s yearly pile of JJCPA dollars are to be spent, was for a very long time operating in a way that didn’t really follow state rules. Specifically, the group was out of compliance with state law when it came to who was included among its membership. And, for many years, it appeared that the members who were included tended to do little more than rubber stamp what probation wanted when it came to allocating the $30 million plus in yearly JJCPA funds—a big chunk of which was used for voluntary probation.

In the spring of 2016, however, there was something of a mutiny among some group members, the upshot of which was that the makeup of the JJCC began to change in a more…well…legal direction. Now the constitution of the group is about to change even further due to a motion passed by the LA County Board of Supervisors at the very end of last year.

The motion, authored by Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sheila Kuehl, will add to the JJCC “10 voting community members,” one appointed by each Supervisorial District, and five new community seats to be approved by the JJCC.

(Probation leadership supported the motion.)

So will this new influx of JJCC members drawn from the community mean some changes in priorities when it comes to deciding how those tens of millions of yearly JJCPA dollars are spent?

As you would expect, WitnessLA will be closely following all of these questions and changes.

So….as always….stay tuned.