“Everyone talks about the school-to-prison pipeline,” said Loyola Law School professor Sean Kennedy. “But doing this work you see that there’s a group-home-to-prison pipeline.”

Kennedy is the Director of Loyola’s respected Center for Juvenile Law and Policy (CJLP), which was founded in 2004 to “tackle the injustices of the Los Angeles County juvenile court system” by providing pro bono advocacy for youth who find themselves caught up in that system.

Now CJLP is gearing up to launch a brand new project to help foster children who have the double-whammy of winding up in the justice system. These “crossover kids” are statistically far more likely to fail in school, and fall into extreme poverty, than kids who are involved in the foster care system or the juvenile justice system separately.

Thanks to a highly competitive $1 million grant from the Everychild Foundation, CJLP has the funds to jump start the program for its first three years.

The Everychild Foundation is a unique organization that makes a single grant of $1 million every year, which is made possible by funds contributed annually by its members. Traditionally, Everychild, which was founded by real estate lawyer turned juvenile advocate, Jacqueline Caster, seeks to fund “innovative projects that have demonstrated their plans are best suited to solve a critical need of children in L.A. County.”

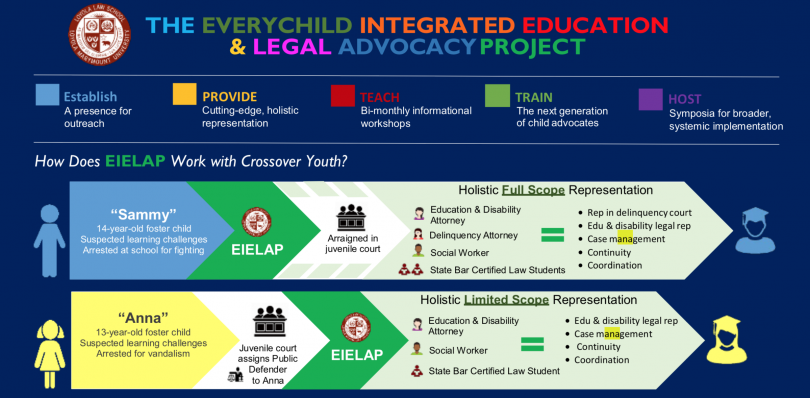

This year’s winning project, submitted by CJLP, is to be called the Everychild Integrated Education & Legal Advocacy Project (EIELAP), and, according to its proposal to Everychild, aims to “help stop the school-to-prison pipeline for crossover youth…” To do so, CJLP’s new program will provide a legal team for their young clients that includes a juvenile-justice lawyer, an education lawyer, and a social worker.

The idea is that the education attorney along with a law student, will “aggressively advocate for the youth’s education and disability rights.” At the same time, a juvenile justice attorney and another law student, will defend the kid in delinquency court.

Among the program’s goals is to train 36 law students to assist at least 300 Los Angeles youth over the course of three years, while also providing the team of lawyer/experts to guide the law students as they represent their young clients and, in so doing, provide a replicable model for the state, and arguably the nation.

“We really wanted to focus on the most at-risk group of at risk kids,” CJLP’s Kennedy said, “kids who are the most high risk because they’ve been taken out of their homes usually due to abuse and neglect.”

Everything gets worse, he said, when these foster kids “act out” because of the trauma they’re dealing with. “They’re arrested, detained and processed though the juvenile justice system,” without attempting to understand the causes of the traumatized young person’s behavior. This kind of narrow-visioned rush to criminally charge suffering young people “is everything this organization stands against,” he said.

Kennedy—-who before he came to Loyola was the Federal Public Defender for California’s Central District—-said with the new program they hope to show that the long term results for a child are far better if “we treat the unaddressed trauma” instead of mostly prosecuting these foster children.

Furthermore, one of the goals for the new program is to trace the outcomes for each of the 300 kids represented by the new program, Kennedy said. With this in mind, the program plans to hire Dr. Jorja Leap, Professor of Social Welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, and a nationally known program evaluator, to track the kids’ outcomes in detail.

The program, said Kennedy, wants to use high quality data “to see if hard core education advocacy can make a difference” for crossover kids “in terms of overall recidivism, in terms of graduation, and in terms of going on to recover and to have a happy life.”

“Erica’s” story

As an example of how the principle works, Kennedy talked about one of CJLPs clients, whom we’ll call Erica.

Thirteen-year-old Erica, said Kennedy, was initially placed with a foster family but, in moment of upset, the young teenager “took the cell phone of the biological child in the family. She took it out of his bedroom.”

Erica’s phone snatching was discovered, and the foster family’s son got his cell phone back. But rather than being grounded, or having some kind of privileges yanked for a designated period, according to Kennedy, the 13-year-old girl “was prosecuted for theft,” bounced out of her foster family, “and sent to a big group home,” where her unhappiness and feelings of rejection increased.

At the group home, he said, one day a miserable Erica threw a clipboard. “It hit one of the adult workers at the home,” said Kennedy, adding that, while Erica had been angry when she threw the clipboard, it wasn’t at all clear whether or not she’d intended to hit the staff member, or if that part was accidental.

In any case, the justice system’s response to the clipboard throwing, according to Kennedy, was to charge the incident as a felony assault with intent to commit great bodily injury.

“And that’s the kind of felony charge that can’t be sealed,” said Kennedy, explaining that, if Erica was convicted, the conviction would come up in a search every time the future adult Erica tried to get a job.

At the same time, he said, the girl had already been having trouble in school because she’d been moved between schools sixteen times.

“One huge issue is that the foster kids are often moved so much it becomes extremely difficult to graduate from school. They never get all their credits.”

But with the new program, the idea is to provide a team that will look at the reasons behind the trauma, unhappiness, acting out, and problems at school for someone like Erica, so that the underlying issues can be focused on directly, said Kennedy. “We can share information with each other and find out what’s really going on in her life.” This allows the team to address underlying causes “along with acting as the young person’s criminal lawyer.”

In real life, Loyola’s pro bono lawyers were able to provide the crucially needed help for Erica, who is now studying to become a paramedic.

“Holistic” representation and education advocacy

In explaining the model he hopes the new law clinic will create, Kennedy talked about “holistic” representation. “We’ll represent these crossover kids holistically as we do for all of our clients in juvenile court, and meanwhile we have our education clinic, which has a very experienced education law lawyer, who will advocate for them to get individualized education plans, get them reinstated in school,” and whatever else is needed.

With this kind of “integrated joint advocacy,” Kennedy said he believes the clinic can produce “better outcomes than the bleak outcomes we too often see now.”

According to Kennedy, the program’s education law specialist is a guy named Michael Smith who used to run the educational law advocacy program for Public Counsel.

To illustrate what educational advocacy looks like in the hands of a lawyer, Kennedy told another story.

“Michael had two kids as clients who were ‘on the spectrum’ and they also became homeless.” When Smith met them, the kids were living out of a van with their parents. Problem surfaced, Kennedy said, because, although the parents managed to get the two kids to school, they rarely got them there on time.

“And because they were late,” said Kennedy, “the kids would be stressed out.” And so like Erica, they would act out. This led to problems at school, and finally both kids were expelled.

Enter CJLP education lawyer, Michael Smith. “He got them back in school,” said Kennedy, with special educational plans (IEPs) “to address their real issues—which were not that they were coming late to school, but that their living situation was very precarious.” Thus someone “needed to address the stress that situation was producing,” along with the children’s other issues.

“So Michael does a lot of IEPs. He does due process hearings. He also gets kids who have intellectual disabilities and mental health problems lifelong benefits, or specialized services or treatments. It’s pretty expansive because the goal is to find out what is causing the educational problem, which in turn, results in kids not going to school or being expelled from school, which can lead to juvenile prosecution.”

This kind of educational advocacy will be one of the main puzzle pieces for the new Everychild program.

Spreading the word

According to Kennedy and Everychild’s Jacqueline Caster, the program’s long term goal is to serve as a model for other cities, counties, and states.

“We are really hoping that this project makes a statement,” Kennedy said. “We not only hope to do high quality, integrated, holistic representation; we also want to study it, and then hold a symposium at the end for representatives of all the parts of the juvenile justice system.” At the symposium, the group will present what they’ve learned about what “works most successfully and what is not successful.” he said.

Kennedy said that the other important long-term goal has to do with training the next generation of public defenders, and juvenile advocates, and public interest lawyers, “to look at public defender work in a different way.”

The hope, said Kennedy, is that “these young, idealistic, energetic law students are going to take that model to public defenders’ offices all over the state, and advocate for those methods.”

Caster agreed. The model that the program is creating, she said, is one “that can be replicated around the nation.”

Caster also talked about the more immediate goal of helping the 300 kids who are slated to be served by the new program in its first three years.

“The biggest problems that these kids face,” she said, is that they don’t have a caring, consistent adult in their lives. That’s what I always hear from the kids themselves. They just want one caring, consistent person who won’t let them down.”

The idea, said Caster, is that Loyola’s new Everychild-sponsored law clinic will provide a whole team of “caring, consistent” people—-who also happen to be highly skilled and very committed lawyers.

We r on same page. Look up the fb page ” Scott Hampton foster care to prison pipeline. We’re on it