California’s Victim Compensation Fund provides crime victims with money for medical treatment, mental health counseling, burial expenses, income loss, and other expenses that arise in the aftermath of a crime. The fund also gives victims access to community Trauma Recovery Centers that provide crucial services to promote healing.

The Victim Compensation Board provides assistance to victims and family members of victims of violent crimes, sex crimes, elder abuse, drunk driving, human trafficking, stalking, and more.

But not every victim of these crimes can access the much-needed supports and services. A bill soon expected to land on Governor Jerry Brown’s desk aims to open up access to more victims.

The CalGang Problem

The compensation board can deny people who are listed in California’s controversial gang database, CalGang, from receiving assistance through the fund.

But CalGang has been criticized for inaccuracies.

A 2016 report from State Auditor Elain M. Howle, found major errors in the database, and revealed a serious lack of necessary state oversight of a system that does not adequately protect the rights of the more than 150,000 people listed in the database.

Howle’s office closely examined 100 individual CalGang profiles. Of those 100, the agencies could not support the inclusion of 13 of the people based on the database entry criteria.

The problems Howle’s audit uncovered captured the attention of advocates and state lawmakers, who, in 2017, tried to address some of the issues by passing AB 90 to ramp up oversight of the database by requiring audits and other regulations to improve accountability and accuracy. The year before, Brown signed a different CalGang reform bill by Weber, AB 2298, which requires that people be notified of their impending inclusion on California’s gang database. Once notified, those flagged for inclusion have the opportunity to challenge the designation, thanks to the new law.

People who admit to law enforcement officers that they are gang members or who have gang-related tattoos are added to the database, but associating with known gang members and wearing clothing that might be gang-related also sends people into the CalGang database. Advocates say the vague criteria often have the effect of penalizing people of color for living in the wrong neighborhood.

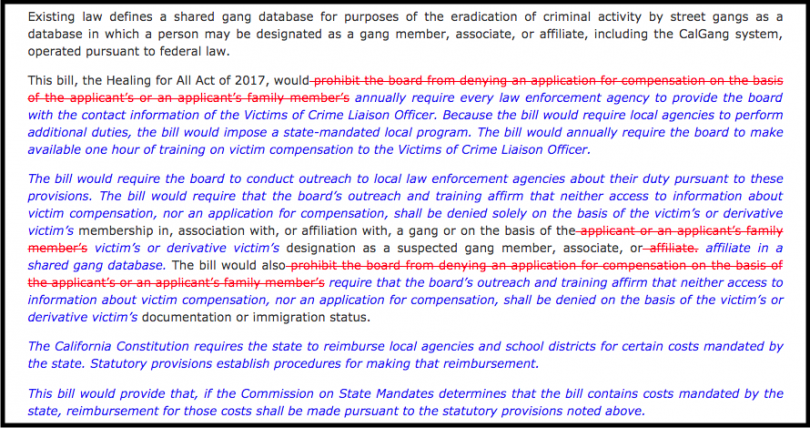

Young black men are both disproportionately added to CalGang, and disproportionately the victims of violent crimes. Which is where Assemblymember Eduardo Garcia’s Assembly Bill 1639 comes in. The bill, which is expected to soon go to Governor Brown for signature, would block the compensation board from denying a compensation claim “solely because the victim or derivative victim is a person who is listed in the CalGang system or alleged by local law enforcement to be gang involved.”

The bill would also explicitly ban the board from denying compensation claims based on a victim’s immigration status.

Furthermore, the bill would direct the Victims Compensation Board to inform and train local distributors of victim compensation funds and services “that they cannot exclude people based on gang allegations or their immigration or documentation status.”

The Victim Compensation Fund, established in 1965, has a history of excluding crime victims from state support.

Until 2013, California was the only state to exclude sex workers from receiving victim compensation after being raped or beaten.

The Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board’s Chairwoman Marybel Batjer was glad to see the “repugnant” rule abolished. “Rape is rape, period,” Batjer said in an interview.

LA advocate group Youth Justice Coalition, is urging Governor Brown to sign AB 1639 to further reduce the number of marginalized victims who are excluded from the fund.

“A comprehensive and holistic, trauma-informed approach to Cal VCB eligibility expansion encompasses a broad, system-wide effort that challenges notions of victimization which discriminate against the recovery of ALL individuals of our communities impacted by crime and violence,” says YJC. “Trauma-recovery and crime survivor coordination of care must include those most at risk to engage in future crime and violence in order to sustain long-term violence prevention and crime reduction efforts.”