We know that, statistically speaking, kids who spend time in LA County’s foster care systems—or any foster care system for that matter—have worse outcomes when they reach adulthood than youth who’ve never wound up in the child dependency system at all.

Over the past few years, new California state laws that are sensitive to this problem, along with community-based programs, and dedicated child advocates, have helped to ameliorate those bad stats to some degree. Yet there is another youth population with challenges and outcomes that are far worse than the statistical stacked deck our foster care children often face. And that group is Los Angeles County’s dual status youth, also known as “crossover kids.”

These are the young people who have the bad luck to fall under the care of two county systems: the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), and the juvenile justice system.

At Tuesday’s board of supervisors meeting, Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas “read in” a motion that aspires to change the double-whammy of bureaucratic harm that so many crossover young people must battle. The idea is to create a multi-disciplinary countywide system to keep foster youth out of the juvenile justice system, while also ensuring that those who end up still being affected by both DCFS and probation, are given the services and caring help they need to heal and thrive.

At least that’s the goal.

The Los Angeles Board of Supervisors will hear the motion, which is co-sponsored by Supervisor Hilda Solis, on March 20th.

Twice unlucky

By definition, foster care youth are victims of serious trauma, Ridley-Thomas said via email when we asked him why he believed the motion was important.

“And getting caught up in the justice system only traumatizes them further,” he wrote. “Half of dual status youth in the county are struggling in school or not attending regularly. Too many end up languishing in juvenile hall due to insufficient community-based placements. We can and must do better.”

No kidding.

The reports on the challenges faced by dual status youth are many and sobering.

In a 2011 report funded by the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation, and updated in 2013, report authors Jacquelyn McCroskey, Denise Herz, and Emily Putnam-Hornstein documented dual status youths’ dismal outcomes in education, employment, health, mental health, and in further criminal justice-system involvement as adults.

The updated report noted, as an example, the fact that half of the crossover youth studied fell into extreme poverty in their young adult years, as compared to only 25 percent of those kids in juvenile probation alone, or 33 percent of LA youth who were in foster care alone. Crossover youth were also more likely to think about suicide or attempt it, than kids in just one of the county’s systems.

One of the biggest problems that dual status kids face, according to youth advocates, is that by being overseen by two big agencies, often no one person seems to have the best interests of these youth at heart enough to make sure they don’t fall into the cracks between the two agencies.

As a consequence, across the U.S., as well as in LA County, according to a 2016 report by the National Justice Justice Network, crossover youth are more likely than are youth with no child welfare involvement, to be arrested or sent to placement in a juvenile facility or a group home instead of simply being given probation. They are also less likely than youth involved only in the juvenile justice system, to be diverted from juvenile court and sent instead into a youth program.

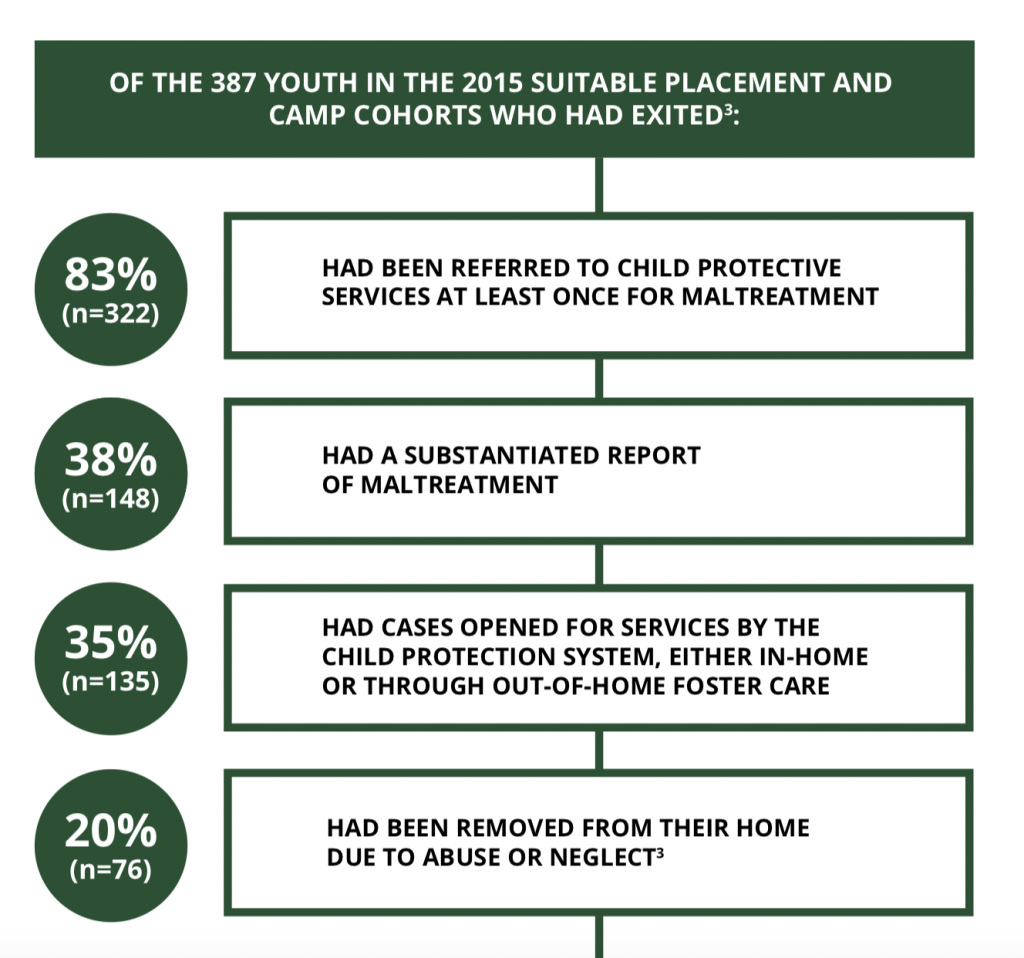

Thus it should not be a surprise that, according to data gathered by the University of Southern California’s Children’s Data Network, in partnership with California State University, Los Angeles (CSULA), four out of five probation youth who are locked up in LA County’s camps and juvenile halls, have previously touched the child welfare system.

Judge Michael Nash Executive Director of the Office of Child Protection, courtesy of Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas

The dual status youth population is also rife with racial and gender inequities. For instance, nearly one half of the county’s crossover cases are African American. And although young women are only 20 percent of the county’s probation population, they represent 40 percent of the crossover cases.

Dropping the ball

Matters have not been helped recent years, according to the motion, that the county has unaccountably stopped certain relevant programs, like its DCFS-led Delinquency Prevention Pilot, “intended to identify high-risk factors that if not addressed could lead to foster youth winding up in the justice system.”

The county also appears to have dropped its support for the highly regarded annual reports and evaluations on crossover youth that had been conducted by Dr. Denise Herz of Cal State Los Angeles.

At the same time, access to needed support services for dual status youth—or kids who seem headed toward dual status—remains limited, according to the motion.

It doesn’t help that LA is still facing a daunting crisis when it comes to finding enough good foster care placements. As a consequence, kids—many of them girls—who act out because of the trauma and loss that sent them into foster care in the first place—reportedly sometimes get pushed into LA’s juvenile halls and because no one knows where else to put them.

As it happens, several of the girls in the face-obscuring photo above at the top of this story were dual status girls that I met in Central juvenile hall a few years ago.

“Why are you here?” I asked one of the girls.

“Because they didn’t want me at the group home any more,” she said. “And they didn’t know where else to put me.”

Two more girls, their expressions wary and resigned, gave me similar answers.

Okay, what to do?

From 2011 Report on LA County Crossover Youth by Jacquelyn McCroskey, DSW Denise Herz, PhD Emily Putnam-Hornstein, PhD

With all this in mind, the new motion instructs the Director of the Office of Child Protection (OCP)—namely Michael Nash, the former supervising judge of LA’s Juvenile Court—in collaboration with all the other relevant county agencies—among them the Juvenile Courts, the Department of Children and Family Services, the Probation Department, the Department of Mental Health, Office of Diversion and Reentry, County Counsel, the Public Defender’s office, the District Attorney, the LA County Office of Education, Office of Immigrant Affairs, and so on, plus LA’s youth advocates—to report back to the board in writing in six months with a written countywide plan to help crossover youth.

“The Office of Child Protection,” states the motion, “created in 2015 and focused on improving communication, coordination and accountability across County child-serving agencies, is well-positioned to play this role.”

And Judge Nash, who said he welcomes “the opportunity,” has long expressed deep concern about the county’s crossover kids, and is likely the right person to lead such an endeavor.

Both LA County Probation Chief Terri McDonald, and new DCFS director Bobby Cagle, also expressed strong support and enthusiasm.

“We believe that by strengthening our partnership and resolve, we can improve the lives of young people who have experienced far too much trauma and often neglect,” said McDonald.

The check list

Among the To Do’s that Ridley-Thomas and Solis want addressed in the plan are the following:

1. Determine the feasibility of incorporating delinquency prevention into DCFS’s mission, and trainings

2. Create strategy to align with any applicable existing plans as the new countywide Youth Diversion project.

3. Develop a coordinated care system to address the needs of youth identified as high-risk for crossing over into the delinquency system.

4. Find strategies to address and minimize the most common ways youth cross over–including consideration of restorative justice alternatives.

5. Find strategies to reduce disproportionalities in which youth cross over.

6. Enhance coordination between the two lead agencies—DCFS and the Probation Department.

7. Create method to enhance referrals and access to appropriate and high-quality health, mental health, substance abuse, housing, education, and employment services for youth and their families.

8. Ensure stable and appropriate placements, while minimizing placements in the juvenile halls and probation camps. (“This is one of the biggest orders,” states the motion. WitnessLA agrees.)

9. Strengthen data tracking and evaluation, which is essential.

10. Determine what policy changes, support, and funding is needed to achieve a new countywide plan and above objectives.

So will any of this matter?

Ordering up a report on a difficult social problem is not a hard thing to do. Using that report to actually do something that matters about that problem is very hard.

But, in this case there is a recent precedent that gives cause for optimism. And that is the historic and extremely ambitious youth diversion plan that the supervisors voted to launch last November.

Judge Peter Espinoza, Director of LA County Office of Diversion and Reentry at Youth Diversion Summit, with Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas/ courtesy of Supervisor Ridley-Thomas

That plan was the result of a similar report that had been ordered up by a motion from the board nine months earlier, in January 2017, in this case the motion was co-authored by Ridley-Thomas and Supervisor Kathryn Barger.

The resulting Division of Youth Diversion & Development (YDD) is now a division of the county health department’s Office of Diversion and Reentry led by retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge, Peter Espinoza.

At the LA Youth Diversion summit held on March 1, 2018, Espinoza announced that the first model version of the program will open this coming summer, with the full countywide diversion program—that it is estimated could affect 13,000 Los Angeles youth—to launch in three years.

Of the more than a hundred county officials, youth advocates, cops, attorneys, formerly incarcerated kids and others who attended that summit, no one appeared to doubt that Espinoza and the broad variety of people working on the venture would do just what he said, and that the lives of thousands of Los Angeles kids would be better for it.

Let us hope that something similar can be done for LA County’s crossover kids.