A 50-state survey by the Prison Policy Initiative reveals a dearth of state laws designed to protect and care for pregnant women and their unborn babies in prisons and jails.

We don’t even know exactly how many women are pregnant behind bars.

Prison Policy Initiative estimates that in 2017, approximately 9,000 imprisoned women were pregnant when they entered lockup. And PPI had to estimate the number because there has been no national accounting of the number of pregnant incarcerated women in the last 15 years.

What is clear, is that, because the number of women behind bars has risen over the last decade, so too must the number of pregnant women have grown.

Jails have exponentially more incarcerated pregnant women and mothers than prisons.

According to a 2016 report by the Vera Institute titled Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform,” nearly 80 percent of 2.9 million women locked in local jails each year are mothers. Most are primary caregivers for their children. Around 150,000 of those women are pregnant.

Yet, many states fail to ensure that pregnant women are receiving the care and support that they need behind bars, despite a clear set of nationally recognized standards for prenatal and postpartum care.

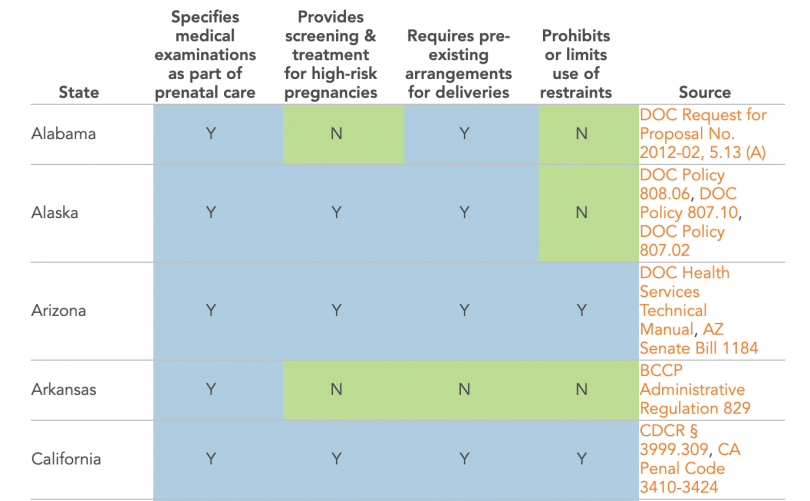

In at least 12 states, for example, there are no laws that require corrections facilities to conduct medical examinations as part of a woman’s prenatal care.

In a 2004 Bureau of Justice Statistics survey, only 54 percent of pregnant women reported that they had received prenatal care while in lockup. (Unfortunately, 2004 is the most recent federal polling of pregnant women in correctional facilities.)

And 31 states lack any policy on nutrition for incarcerated pregnant women. In 12 of the states that do provide guidance, the rules are beyond vague, requiring corrections officials to ensure women have “adequate” or “appropriate” nutrition. California stands apart from all the rest of the states, with a clear requirement that women get specific supplemental nutrients, as well as two extra servings each of milk, fruit, and veggies per day.

“Unfortunately, California was the only state found to have provided a meaningful nutrient breakdown of additional food allowances for pregnant women,”PPI’s Roxanne Daniel writes.

In 2019, the Prison Law Office toured the Arizona State Prison Complex at Perryville, and received reports from women that the facility had failed to provide them with enough fruit and veggies, and that staff only offered them one extra carton of milk and one extra peanut butter sandwich per day. (Arizona law says that incarcerated women must receive an extra 300 kcal and 10g of protein per day, as well as prenatal vitamins.)

Yet, according to experts, including the American Public Health Association, when pregnant women consume nutritionally inadequate, unbalanced diets, they risk having preterm births, birth defects, and other health and developmental problems in their young children.

Incarcerated women are already more likely to have complicated pregnancies and deliveries due to problems like poor nutrition and substance use disorders. Only a little more than half of states offer legal guidelines for care specific to high-risk pregnancies, however.

A startling 24 states have also failed to produce laws that require lockups to have predetermined arrangements for deliveries. Given this, it’s less surprising, but no less horrifying, that women are sometimes left to give birth in their cells.

In one recent case, Diana Sanchez, a 26-year-old pregnant inmate in a Denver County jail was forced to give birth unassisted by a doctor or medication, alone in her cell. Sanchez had spoken with medical staff and jail deputies, telling them she was going into labor hours earlier, but no one came to take her to a hospital.

In many states, guards can also still shackle pregnant women to the bed while they deliver their babies, despite the high unlikelihood that a woman giving birth is either a flight or public safety risk. (Most incarcerated women are locked up for nonviolent crimes.)

A dozen states have no laws that ban or limit the use of physical restraints like shackles on pregnant prisoners. Recently, the First Step Act banned the practice, often criticized as inhumane and traumatizing, in federal prisons.

“Given the scale and stakes of this issue, it is imperative that correctional systems set policies that ensure the health and well-being of pregnant women in their custody,” writes Daniel. “Provisions for adequate nutrition and prenatal medical care must be codified in policy to protect against negative health outcomes, such as miscarriages and low fetal birth weights, that can impact mothers and their children for the rest of their lives.”