According to a report released this week by the Prison Policy Initiative, since 2009, a movement toward justice reform, along with the high cost of over-incarceration to cash strapped states, has slowly reduced state prison populations around the nation. Yet, according to the new report, in the majority of states, the decrease in numbers has been among male inmates, not women in jails and prisons.

Some state, California among them, were successful in also bringing the women’s numbers down.

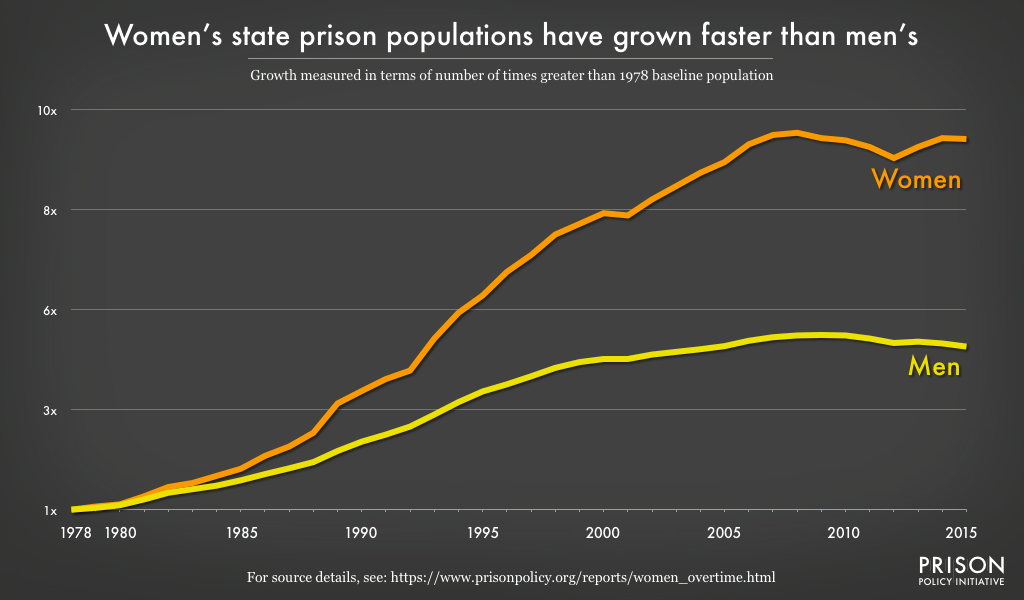

When the state numbers were aggregated, however, nationwide, women’s state prison populations grew 834% over nearly 40 years, more than double the pace of the growth among men.

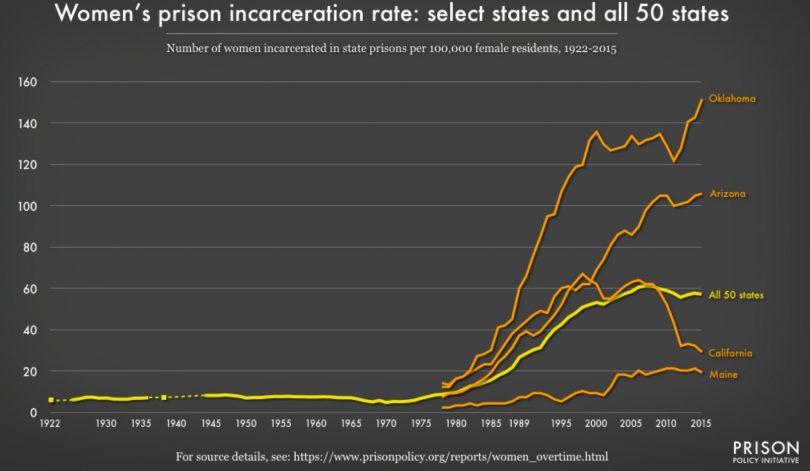

As the PPI looked deeper into the state-specific data, they identified a large cluster of states that were driving the disparate figures.

“In 35 states, women’s population numbers have fared worse than men’s,” wrote the report’s authors, “and in a few extraordinary states, women’s prison populations have even grown enough to counteract reductions in the men’s population. Too often, states undermine their commitment to criminal justice reform” by ignoring the issues surround women’s incarceration.

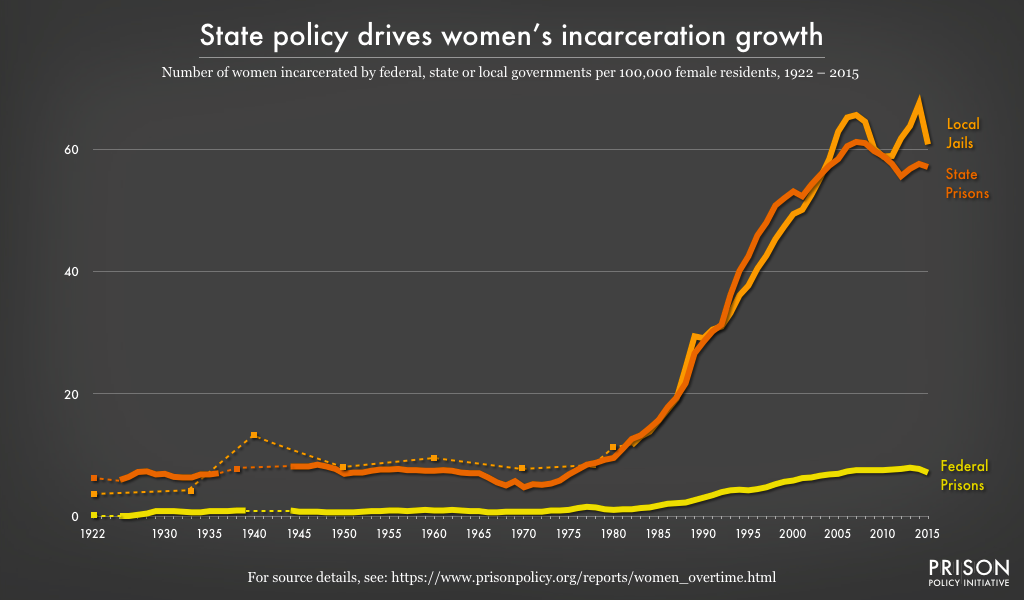

Interestingly, women’s populations were not jumping at a federal level, the authors found. But at in the state level, there were some startling spikes that the report’s authors said were often poorly understood.

“Behind women’s outsized incarceration rates is a justice system that, by and large, ignores the systemic hardships faced by women,” the Prison Policy Initiative’s Wendy Sawyer told Colorlines. “Women are more likely to enter prison with a history of abuse, trauma and mental health problems. On average, incarcerated women are substantially poorer than incarcerated men, and they are much more likely to be the primary caretakers of children.”

County jail numbers were also prime contributors to the state incarceration numbers for women, according to an October 2017 report produced jointly by The Prison Policy Initiative and the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice, which showed that under half of the approximately 219,000 women incarcerated in the United States right now are in local jails, and 60 percent of these jailed women have not been convicted, but are still awaiting trial.

Sawyer’s point about the prevalence of abuse, trauma, and mental health issues for female inmates is further supported by a July 2017 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics showing that two thirds (66%) of all women in prison report having a history of mental health problems, as compared to 35 percent of male prison inmates.

When it came to U.S. jail inmates, the female/male mental health discrepancy was nearly as dramatic, with 68 percent of female jail inmates having been told they had a mental disorder, versus 41 percent of males in jail who had received such a diagnosis.

Why is progress slower for women?

“Although we can identify some of the reasons for the outsized growth of women’s incarceration, it’s harder to say why progress toward reversing prison growth has been slower for women,” wrote the report’s authors.

Yet there are some gender differences in police and practice that have been have already been identified that affect criminal justice involvement for women that policy makers would be wise to heed, according to the report:

1. While they are incarcerated, women may face a greater likelihood of disciplinary action — and more severe sanctions — for similar behavior when compared to men. Disciplinary action works against an incarcerated woman’s ability to earn time off of her sentence and against her chances of parole.

2. Fewer diversion programs are available to women. In Wyoming, for example, a “boot camp” program that allows first-time offenders to participate in a six-month rehabilitative and educational program in lieu of years in prison is only open to men. Because no similar program is available for women in the state, women in Wyoming can face years of incarceration for first-time offenses while their male peers return quickly to the community.

2. States continue to “widen the net” of criminal justice involvement by criminalizing women’s responses to gender-based abuse and discrimination.

3. Overcriminalization of drug use and peripheral involvement in drug networks has long been noted as driving driven women’s incarceration growth.

4. Other policy changes have led to mandatory or “dual” arrests for fighting back against domestic violence, increasing criminalization of school-aged girls’ misbehavior — including survival efforts like running away — and the criminalization of women who support themselves through sex work.

Fortunately, California is one of the states that has made strides in some of the last issues. But much more is needed in nearly every state said the Prison Policy Initiative.

“The mass incarceration of women is harmful, wasteful, and counterproductive; that much is clear,” the authors wrote. But it is also clear, they said, that the nation’s understanding of the reasons behind women’s incarceration suffers from a vexing scarcity of gender-specific data, analysis, and discourse.

This report aspires to lay the groundwork for states to engage in asking some critical questions as policy makers (hopefully) “take deliberate and decisive action to [further] reverse prison growth.”