In the world of family violence, the focus is on healing victims. The survivors.

This means a strong emphasis on raising funding for domestic violence shelters, thousands of research projects, state and federal legislation, and work to change the criminal justice response.

But that approach provides help for only half the people involved in the problem.

Batterers, the other half, have one option, generally speaking: punishment. Go to jail and/or complete a 26- or 52-week batterer intervention program. Every year, about 500,000 people receive sentences to take one of a hodgepodge of about 2,500 programs. Most of these require participants to take responsibility “for their sexist beliefs and stop abusing their partners by teaching them alternative responses for handling their anger.”

The programs focus repeatedly on how badly abusers have behaved. There is little effort to help them understand that their anger comes from childhood trauma and that naming and acknowledging those experiences can lead to accepting their behavior and then healing.

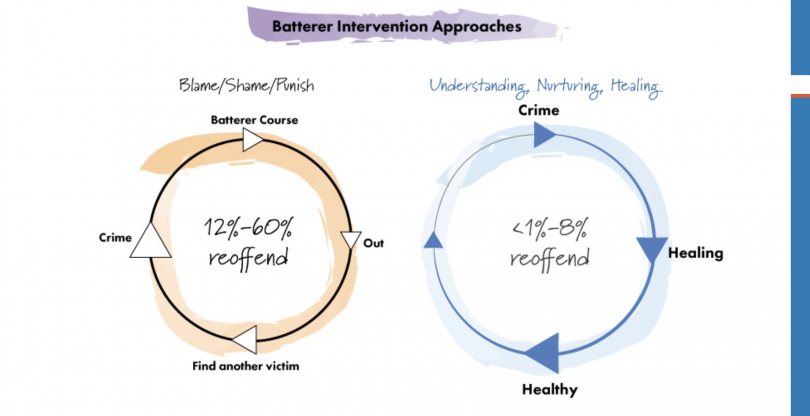

Here’s the hitch, and it’s a costly one. As a result of this traditional approach, 12% to 60% of participants in batterer intervention programs are re-arrested for abusing their partners.

It’s no surprise that domestic violence is still so prevalent and that the numbers of domestic violence calls to police haven’t changed much over the last few years. The dearth of research into figuring out what works to help an abuser to stop abusing “is such a neglected area of study that the field has almost ceased to exist,” according to a paper published this year by Casey Taft and Jacquelyn Campbell. That’s shocking, considering that the economic toll of domestic violence in the U.S. rolls into the trillions of dollars.

Some bright spots have emerged that offer realistic hope to drastically change these numbers. They’re based in science and data, not “clinical assumptions and lore,” as Taft and Campbell describe the current system.

These programs take a healing approach.

Their re-arrest rates range from near zero to 8 percent.

Moving from blame, shame and punishment to understanding, nurturing and healing

Over the last several years, two women—Nada Yorke and Dr. Amie Zarling—began developing batterer intervention programs independently; both took a healing-centered approach. While Yorke focuses on writing curriculum and training, Zarling focuses on research and training. Both operate on the premise that if your only experiences are abusive, how do you know what’s healthy? How do you NOT pass on the unhealthy aspects of a relationship to your children?

Both encourage program participants to understand how experiences influence their decision-making, and both encourage participants come to their own realizations by experiencing the “confusion and frustration”, as Zarling says, that comes with learning concepts that require a completely new mindset. Both include information about what healthy relationships look like, understanding thoughts and where they come from, effective listening and speaking, and resolving conflict. They included the science of positive and adverse childhood experiences as a foundation. And they developed ways to distribute their programs to thousands of people and communities.

Yorke, who retired from her job as a probation officer in Kern County, California, followed her curiosity into this work because she wondered why men arrested for abusing their wives were often re-arrested after participating in a batterers’ intervention program. As part of a master’s program in social work, she developed and tested her program in Kern Valley State Prison in Delano, California, and at Garden Pathways, a family services organization in nearby Bakersfield. There, she began following the first pilot group.

Of the 47 men who started the program, 32 finished, an unusually high retention rate that has been repeated with subsequent groups. After 30 months, only one of the 32 men who finished the program was re-arrested for domestic violence; of the 15 who did not complete the program, 5 were re-arrested for domestic violence. The results also showed that those who completed the program took personal responsibility for the abuse they committed. This was enough to convince Yorke that a healing approach could make a huge difference.

She followed the group for eight years. Those who completed the course had a re-arrest rate of less than 20 percent. Of those who didn’t complete the course, 53 percent were re-arrested on domestic violence charges.

“You have to allow opportunities for the participants to share the experiences that shaped and influenced their own behaviors and then teach them different ways to cope,” says Yorke. “How can you respect and love somebody else if you don’t know what it looks like, or if you haven’t felt respect and love?”

Today, a few hundred probation departments and family services organizations across the United States and in several countries teach her curricula, Another Way…Choosing to Change. Some gather recidivism data; others don’t. She has written three editions of facilitator’s guides and participant handbooks for men in English and Spanish, for women who are abusers, and is working on a version for youth.

Garden Pathways has collected recidivism data the longest through their Breaking the Cycle batterer intervention program, which uses Another Way. Of the 324 people who completed the program from 2011 through 2022, 26 people (8 percent) were rearrested for domestic violence. For those who didn’t complete the course, the re-arrest rate was 12 percent. COVID has had an effect: Between 2011 and 2017, the recidivism rate was 4 percent.

Trivium Life Services, which offers behavioral health services in Idaho and Iowa, also uses Another Way in their batterer intervention program for men on probation. In Boise, Idaho, over the last three years, 393 men have completed the program. “I see the arrest reports every day,” says Steve Mitchley, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran and social worker who teaches four classes a week that use the curriculum. “Only one person has been rearrested for felony domestic violence.”

Meanwhile, in 2009, the Iowa Department of Corrections (DOC) determined that the traditional Duluth Model, which with cognitive behavior therapy has been the standard for more than 30 years for batterer intervention programs, did little to improve re-arrest rates compared to no treatment. In January 2011, they embarked on a three-year pilot program to test Achieving Change Through Values-Based Behavior (ACTV, pronounced “active”).

Zarling, then a post-doctoral graduate student in clinical psychology at the University of Iowa, developed ACTV with Dr. Erika Lawrence, now at the Family Institute at Northwestern University, with input from forward-thinking people at the Iowa DOC. She believes that since people’s emotions often drive their decisions, the program needs to address those emotions and their roots. The Duluth Model maintains that the reason men batter is to control their partner and to maintain power in the relationship; addressing their emotions excuses their actions.

“Talking about emotions is seen as justifying the violence,” says Zarling. “Well, you can’t talk about adverse childhood experiences without talking about emotion. I feel like they discard childhood trauma because, well, then you have to talk about emotions, and we don’t talk about emotions because that excuses the violence. I mean, I have nothing against Duluth in the sense that what they teach is fine. But it’s what they don’t teach that I have a problem with.”

In fact, both Yorke and Zarling include components of the Duluth and cognitive behavior therapy models—including stress management, establishing safety and rapport, how control is used and alternatives to control. What they also include is the basic understanding that domestic violence doesn’t always involve a woman and a man, and that the conflict between them is due to a man’s sexist beliefs is outmoded. Family violence is a more accurate term because it occurs between parents and adult children, between siblings, between members of generations in the same family, or between two LGBTQQ people.

Zarling’s first major study was to compare outcomes of ACTV with the Duluth Model. After reviewing records for 1,353 men who participated in ACT and 3,707 who used the tradition Duluth model, only 3.6 percent of the men were re-arrested for domestic violence after going through ACT, compared with 7 percent who used the Duluth model. After the study, Iowa’s DOC was sold. Zarling led the training of more than 500 people across the state to use the ACT course, in which 15,000 men have participated. Based on Iowa’s success, the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services has decided to implement the program in its prisons.

Because the first ACTV project wasn’t set up as a randomized control study in which people are randomly assigned to one program or the other—the gold standard in research—Zarling embarked on a new study that was published last year. She had randomly assigned 338 men to the ACTV or Duluth Model, but the COVID pandemic forced an end to the study before she was able to engage the more than 400 she’d planned on. Although results showed recidivism rates were lower for ACTV (9%) than Duluth (13%), Zarling says that the results aren’t statistically significant. However, the feedback from victims, an important part of the study, showed that “physical aggression, controlling behaviors and stalking behaviors” decreased in the men who participated in ACTV. Meanwhile, in 2020, Lawrence led a separate study of 725 men in Ramsey County, Minnesota, where ACTV has been implemented since 2013, that showed similar results. Zarling’s current research looks at how taking the ACTV course affects current inmates in prison who have a history of abusing their partners.

To be clear, other healing-centered programs exist that have similar results as those of ACTV and Another Way. They include the Family Peace Initiative, which operates in four cities in Kansas; Men Creating Peace in Oakland, CA; A Safe Way Forward in New York City; and the Alma Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. These programs are focused locally or regionally or don’t do research. Some keep recidivism data. Other programs are also being evaluated, including a three-year program in six counties in California to evaluate alternatives to punishment-based programs.

Learning how childhood adversity from the past plays out in the present, and how to heal

“I’ve always solved problems with my fists,” says Rene Albert Ambriz, 50, who works for a nonprofit that weatherizes low-income homes in Bakersfield, California, and whose hobby is mixed martial arts. He was arrested when his 17-year-old stepson accused Ambriz of roughing him up when he made him leave the house for lying to his parents.

In this case, Ambriz says he didn’t use his fists to solve a problem. “I was falsely accused,” he says, and was irate that he was arrested. “But at the end of it all, it was a blessing in disguise. I found a mentor and a friend in Ray (Fisher, who taught the batterer intervention course) and a new calling in life.”

“The course just totally changed my mind,” he says. His father died when Ambriz was a boy; then his mother married an abusive man. He learned that the families that he saw on TV shows when he was growing up didn’t reflect the real world of families grappling with daily violence. The course showed him that what he experienced was the norm, not the exception, not only because everyone in the course had similar childhood experiences, but because he learned that two-thirds of people in the U.S. have had some type of childhood adversity. The course fostered a camaraderie that is ongoing.

Among the many tools that help him think differently about how he interacts with others, one stands out for Ambriz—learning how to listen. “Just listen, offer an ear. Not say anything.”

Although Ambriz hated the course when he first started, his mindset is radically different now. “Once you let go of what happened to you in childhood,” he says, “you can start living.” The experience so impressed him that he decided to emulate Fisher: “I want to be a counselor now and help others.”

Learning critical thinking was a new skill for Anthony Gonzales (Tony) Stig, 35, another participant who works for Frito-Lay in in Bakersfield, California. “I didn’t feel like I was being told what to do,” he says. “I felt like I was being told: ‘Hey, we learned this lesson. How do you think it might benefit you in your life or your work life or while you’re here with us?’”

“Ray would always ask open-ended questions,” Stig continues. “Instead of saying, ‘Hey, why don’t you try this next time?, it was more ‘Tony, what do you think about the way she or he felt about this?’ so we could figure it out for ourselves, which has been the most wonderful thing that I’ve ever used and now I use in my personal relationships.”

What’s been most valuable, says Stig, is how he can easily recognize why he’s having a bad day and pinpoint the trigger. “I can identify the trauma and how to work it out within myself,” he explains. “And most of all, how not to take it out on others. And me being a father is probably the most important thing that drives me to change from within and to accept these lessons.”

Stig was arrested after getting drunk when he learned his mother received a terminal cancer diagnosis. He kicked over a heavy coffee table, which landed on his grandmother’s foot. Neighbors heard the commotion and called the police. Although his grandmother’s foot wasn’t broken, it was bruised. Harm is harm. He was taken to jail and eventually offered the batterer intervention course and two years of community service in lieu of being locked up.

“I wasn’t innocent, because I shouldn’t have been drinking, especially out of emotion and sadness. And I’m glad I didn’t really hurt my grandmother by accident,” Stig says. He now understands that he had been coping with his childhood trauma by using alcohol and anger. His childhood trauma included losing his father when he was a baby and parenting six brothers and sisters from the age of 12 because his mother and stepfather worked long hours. Being responsible for his siblings at such a young age “was too much,” he says. “It was always overwhelming.”

Fisher understands Ambriz and Stig well. He’s been in their shoes. Jailed three times for a total of 10 years on domestic violence and other charges, he was required to take a batterer intervention course as a condition of his last parole. When he ended up in Yorke’s pilot program at Garden Pathways, it completely changed his mindset about why he ended up in jail—that he was born bad and that the things he did to end up in prison proved he was bad. The course altered the trajectory of his life.

“When I got out of prison and took the batterer intervention course in 2015, I taught everything I learned to my family members,” says Fisher, who has 12 children. “And I lived it so that I could demonstrate it for them with my wife, teach them how to live.” Recently one of his sons, who’s now 23, thanked him for that.

He took Yorke’s 40-hour course to become certified to teach Another Way, which he does at Vanguard Community Center in Bakersfield once a week. He commutes from Lompoc, where he’s a full-time drug and alcohol counselor at Legacy Village, which provides inpatient treatment for veterans and active-duty military personnel.

Participants begin changing their mindset after 14 or 15 weeks, says Fisher. It takes that long to build a rapport with them. No longer angry, they’re also open to new ideas. When they fill out a questionnaire about their childhood trauma, “some get pissed off,” he says. “They’re guarded. I tell them it’s an effective tool to understand why they use the behavior they do. Eventually all understand that batterers and victims come from the same soup.”

The ‘why’ and ‘how’ of healing from family violence

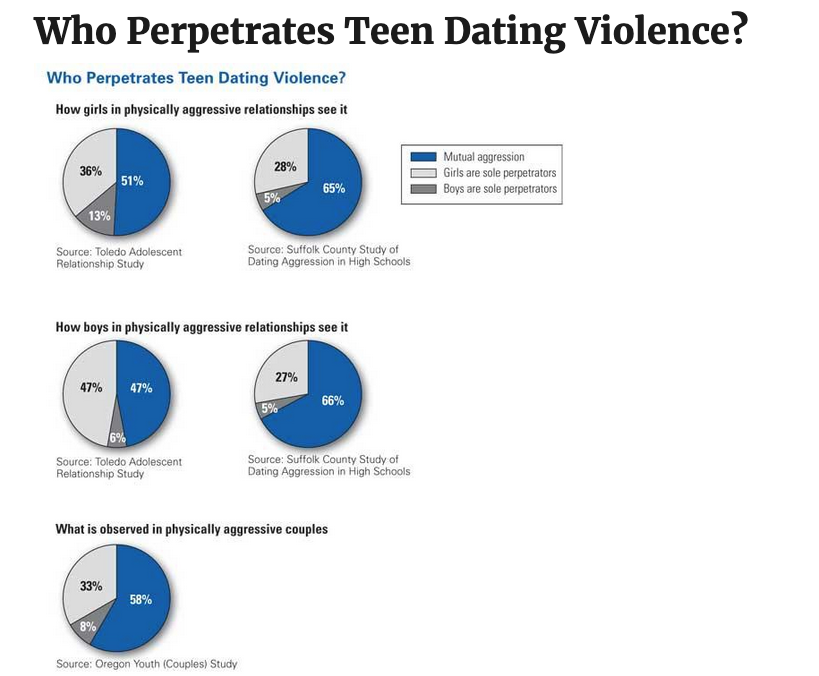

The science of childhood adversity clearly shows that the people who commit family violence as well as the survivors of family violence do indeed simmer in the same soup while they’re growing up. As teens, they even flip between experiencing abuse and being the abuser. Adults who experienced family violence as children were also likely to experience the other types of adversity that accompany the physical, verbal and sexual abuse of family violence, including emotional and physical neglect, living with a parent or guardian addicted to alcohol or drugs, and being homeless. In fact, teen dating violence has been designated as another type of adverse childhood experience.

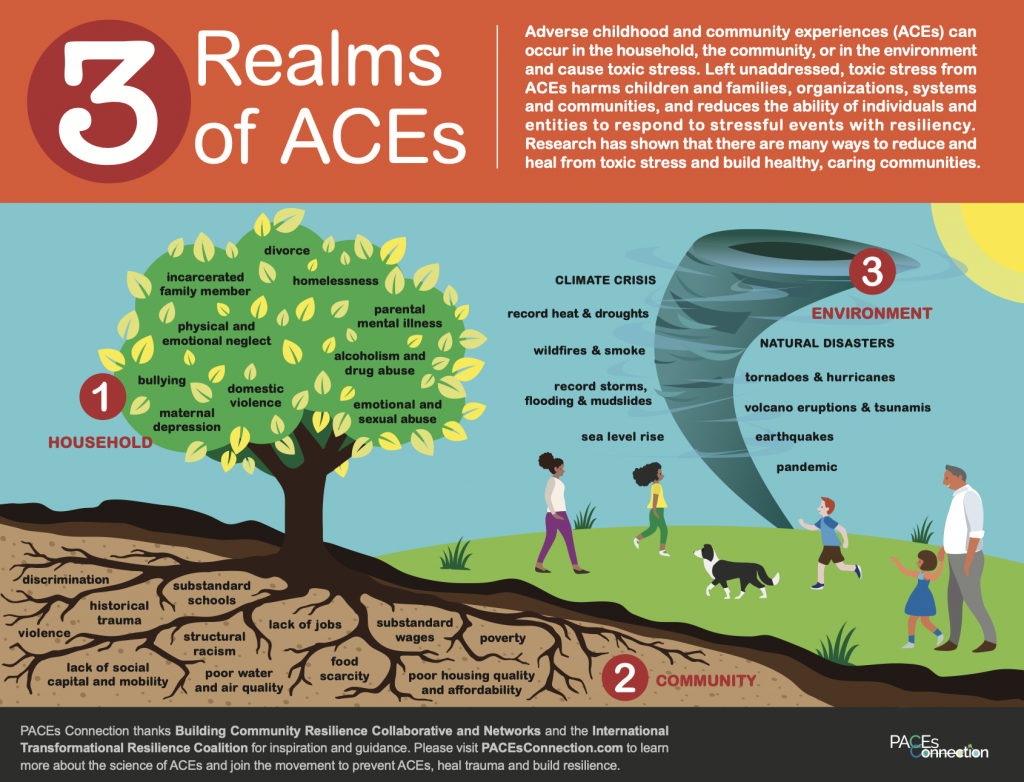

Understanding the link between childhood trauma and family violence link came about with the revolutionary CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experience Study (ACE Study). Many people who’ve heard about the ACE Study think it’s all about finding your “ACE score” by answering 10 questions. Were you sexually, physically or verbally abused? Were you physically or emotionally neglected? Did you witness your mother being abused? Are any of your family members addicted to alcohol or other drugs? Have they been incarcerated? Did you experience the loss of a parent through divorce, abandonment or death?

But now, many other types of childhood adversity are also recognized as ACEs, including experiencing racism, sexism, homelessness, teen dating violence, or war; witnessing a sibling or father being abused, losing a family member to deportation, being bullied, living in an unsafe neighborhood. The list goes on.

These experiences—especially if people endure 4 or more ACEs—can lead kids to react with severe stress…toxic stress that damages their brain and delays healthy development, causes short- and long-term mental and physical health problems, and can be passed on to their children and grandchildren. People with high ACE scores that indicate they’ve experienced a huge amount of toxic stress are more likely to be violent and victims of violence, to have more marriages, more broken bones, more drug prescriptions, more depression, and more autoimmune diseases.

The good news is that positive childhood experiences can counteract the effects of ACEs. Positive experiences include the ability to talk with family about feelings, having a supportive family, participating in community traditions, a feeling of belonging in high school and being supported by friends, and having at least two adults, other than parents, who genuinely care…practices that healing-centered programs teach.

Understanding the science of childhood adversity opens the door to the change in mindset that occurs in healing, says Dave Lockridge, CEO of ACE Overcomers and a former pastor. People learn that:

- They weren’t born bad.

- They had no control over their childhoods.

- They coped with the stress of their ACEs understandably, given that they were not provided healthy alternatives. That coping includes drinking, violence, rage, over-eating, engaging in thrill sports, and addiction to sex, gambling, and shopping, among other coping mechanisms.

- They can change.

A couple of years into developing her batterer intervention program, Yorke learned about the science of childhood adversity. She decided to integrate information about the ACE Study and the 10-question survey into the program and learned that many of the participants had high ACE scores. She discovered that scores of 7, 8, and 9 were common.

“Learning about the ACE Study showed them that they’re not crazy, that they’re not weak, that they were primed for choices and behaviors,” she says, “And now this knowledge gave them an opportunity to boost their esteem in a healthy way and to build in resilience.”

She provided information about the consequences of high ACE scores, such as that for people with an ACE score of 4 or higher, their risk of becoming an IV drug user increased 800 percent; becoming an alcoholic, 700 percent; attempting suicide, 1200 percent.

“There was a guy who was an IV drug user,” recalls Yorke. “He said that it was the first time he realized that he wasn’t a bad person…a weak person who couldn’t manage life. I told him, ‘You were already primed to turn to drugs to escape from your life issues.’

Some in her class were reluctant to take the survey. Yorke recalls one man who kept saying, “I have no issues in my home.” But she knew his background, and the fact that he was in and out of prison belied his answer.

“So, I told him: ‘OK, you don’t have any issues. So, fill it out for your child.’ That got to him, and he was able to see that his child was experiencing what he had experienced. It was amazing just to see their eyes open to how their past experiences had influenced their choices. When they see their children on the same path, and they understand that they can mitigate their kids’ experiences, it motivates them to learn how to handle stress differently.”

Even though only one part of their many-week programs are devoted to the science of childhood adversity, both Zarling and Yorke understand it’s the key to the “why”…why people turn to violence in their families as a solution for their traumas. The remainder of their programs are devoted to the “how”…how to heal.

****

Author Jane Ellen Stevens is the founder, publisher and editor of Aces Too High, where this story first appeared.

All photos are also courtesy of Aces Too High.

Next from Jane Ellen Stevens and Aces Too High: The promises and limits of healing-centered batterer intervention programs; a closer look at communities that listen to families—”help us heal, don’t make life harder”

So watch for Chapter 2, coming soon