Editor’s note: Whatever you do or don’t think about the controversial and complex case of the Menendez Brothers, a look at their recent bid for parole opens the door to an examination of how well or poorly our systems of prison discipline presently work. So read on!

PS: if you’ve not already read Part 1 and Part 2 of this series by, our friend Chandra Bozelko, begin here

****

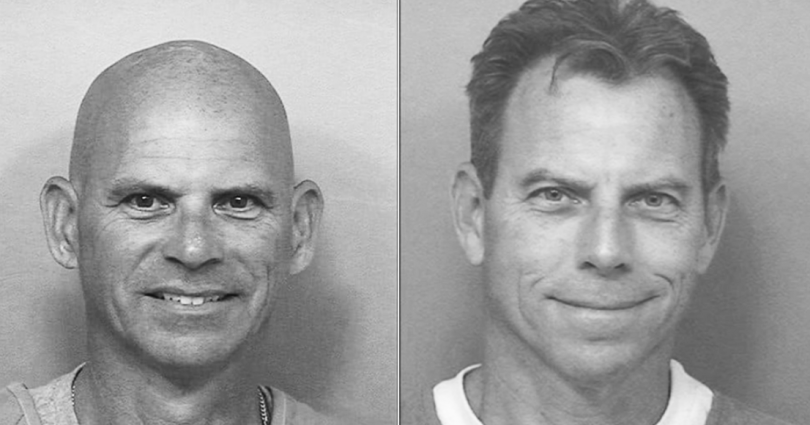

Parole commissioners told each brother that he was not a model inmate, the suggestion being that only a “model inmate” can expect to be paroled.

The Menendez’ brothers’ disciplinary records paint a picture of the difficulty of being a model inmate for others who are less well known than the brothers, but like them have logged almost 30 years in California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) custody.

Los Angeles County District Attorney Nathan Hochman said Erik’s “conduct in prison and current mentality demonstrates that he still poses an unreasonable risk of danger to the community.” Hochman said Lyle’s rules violation history “raises serious concerns about how he might behave if released.”

Admittedly, some of the brothers’ disciplinary offenses are very serious and they confess they broke the rules. Both were caught with cell phones as recently as 2024. Possessing a cell phone in prison is a crime under California law.

Neither brother was charged, as the statute is usually used against staffers who bring in devices. But these instances of misconduct likely sealed the brothers’ parole denial.

But other offenses — like leaving an antidepressant pill in a cup, rather than taking it, as Erik did — are arguably overblown.

Some of the brothers’ rule violation reports were disputed in a system that doesn’t empower the prisoners who profess innocence in a disciplinary hearing. One alleges that Erik put his hands on a female visitor. Erik not only denied the allegation but also filed a complaint of his own about the situation. The lieutenant who decided Erik’s appeal conceded that the video evidence was not clear about what happened.

Lyle Menendez has been portrayed as the “bad” brother due to his assertive demeanor, leadership in the crime, and popular movies and series that exaggerate his negative traits. But some of his disciplinary records show Lyle to be violence-averse.

In September 1996, Lyle refused to leave Administrative Segregation and join the general population. Hardly disorderly, he was daunted by the prospect of living in prison versus jail, which is unusual since Los Angeles County jails are often described as more chaotic than prisons, by those who have resided in both. Even in the more stable setting of prison, Lyle refused to fight other inmates and requested protective custody.

Picking apart the Menendez discipline files shows that prison infractions aren’t always evidence of antisocial tendencies, but may just be the results of navigating a discipline process that is less than ideal.

Why the brothers story captures us

The Menendez brothers embodied a particular strain of Southern California privilege, growing up in the wealth and glamour of Beverly Hills where appearance and status often meant everything. Their story captured the dark underbelly of the California dream—the sun-soaked mansions and tennis courts masking deep family dysfunction and eventually explosive and fatal violence. The case became a media spectacle that felt uniquely—not just Californian but Los Angelean—with its mix of Hollywood-adjacent drama, courtroom theatrics by iconic characters like defense attorney Leslie Abramson, and—perhaps most importantly—the public’s fascination with the fall of the golden and privileged.

That may be why District Attorney Hochman leans on these instances of misbehavior whenever he opposes the brothers’ release: the public has always expected better of the brothers and when they don’t measure up, the expected response is to punish them.

Interestingly, the media characterizations that counted the brother’s parole denials as a loss missed much of what was said in the proceedings. Each ended on a hopeful note. Commissioners told them that they could be back in front of the board within about a year and, if each came back after a discipline-free period, they could be deemed suitable for release.

For the first time in 35 years, the two can envision coming home. Robert Rand, the journalist who began covering the Menendez brothers’ case in 1989 and was a consultant for the NBC series “Law & Order True Crime: The Menendez Murders,” says that the two are “elated” by the parole decisions.

After the brothers’ hearings, advocates renewed calls for reform of California’s parole system, although it’s one of the better ones in the country.

Yet, perhaps the primary lesson offered by the Menendez parole hearings isn’t specific to the siblings. It’s a larger one, namely how the lack of an opportunity to redeem oneself often leaves people with no reason to improve.

*****

Author Chandra Bozelko covers the criminal justice system. She is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Ethics Committee and serves as Vice President of Board of the New York Press Club. She won the 2021 Sigma Delta Chi award for Online Column Writing..