In January, California Governor Jerry Brown released a budget blueprint that included several criminal justice system reforms. One of the most controversial of those reforms is a proposal to increase the age cap for youth under the jurisdiction of the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) from 23 to 25.

In 2012, the state stopped placing 24 and 25-year-olds in DJJ detention facilities in order to save money and to reduce the youth inmate population in state facilities.

Now, however, the most recent advances in brain research has changed thinking about when full adulthood actually begins.

“New research on brain development and juvenile case law around diminished culpability of juvenile offenders has prompted the administration to reevaluate this decision,” the budget states.

The new plan would mean that kids sent from juvenile court to DJJ, as well as kids convicted in adult court, but whose sentences would conclude before age 25, would be able to stay in juvenile facilities until the proposed age 25 deadline.

On Tuesday, the California Legislative Analyst’s Office released a 64-page evaluation of Governor Jerry Brown’s proposed juvenile and criminal justice spending for the upcoming fiscal year, including the proposed age hike.

The LAO, in its report, recommends that the state legislature approve Brown’s proposal to raise the age, “given that research suggests that youths generally have better outcomes when they remain in juvenile court and/or are housed in juvenile facilities rather than prison,” the LAO states.

Yet, the report also urges caution about the age change. Because the “actual effectiveness of these proposals is uncertain,” states the LAO, lawmakers should only approve them on a limited basis, and should require the state to conduct evaluations once the changes are in place, in order to take a second look at their effectiveness.

Additionally, the LAO report calls on legislators to modify Brown’s plan to ensure that young people sent from juvenile court to DJJ facilities don’t get stuck behind bars for two years longer than they would have under the current system.

Most kids who break the law, if they are remanded to a juvenile facility, are housed at the county level. The LAO report points out that juvenile court judges do not hand out set sentences to minors. Instead, they look at kids’ offenses, their history, and other factors and decide where to place them, and what rehabilitative treatment they should get.

However, juvenile court judges can also choose to place youth in state-run facilities for serious crimes like murder, robbery, and certain serious sex offenses. This happens infrequently. Out of approximately 41,000 juvenile court cases, judges sent 183 kids—less than one percent—to DJJ.

Because these kids don’t have a set sentence, they are either released when the Board of Juvenile Hearings says they’re ready, or they are released just before their 23rd birthday.

Juvenile justice advocates and the LAO worry that, with the proposed rule change, some of these youths may needlessly spend an extra two years in lockup.

“This is potentially problematic because research suggests that keeping a youth in treatment programs for a longer period of time than required on average does not appear to increase the effectiveness of the programs,” the LAO report states. “Given that this would also increase the costs of housing these youths, it is unlikely to be a cost-effective way to reduce recidivism.”

Propping up a failing system?

Back in January, the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice slammed Brown’s budget proposal, saying it would “prop up the failing system and extend its harms to a new population of young people.” What the state should do, according to CJCJ, is invest in community alternatives that keep kids out of state facilities, rather than expanding DJJ.

“By raising the age of jurisdiction, Governor Brown would reverse a decision made in the 2012-13 budget cycle to lower the maximum age of youth confined in the facilities,” CJCJ policy analyst Maureen Washburn wrote. “In the years following this reform, the average length of stay at DJJ declined modestly, suggesting that a reversal of the reform could lengthen the period youth spend at the facilities, including those committed by juvenile courts.”

Brown’s plan also includes a Young Adult Offender Pilot Program, which would give the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation more power to send youth in adult court into DJJ lockups. The CDCR would be allowed to place as many as 76 youths in two currently empty DJJ units. The young people would have to have been convicted in adult court, have committed crimes before they turned 18, have been adjudicated between ages 18 and 21, and be able to complete their sentences before age 25. If space is available, CDCR would also be able to send youth who committed crimes after age 18 but fit the other requirements to the DJJ units.

Based on Brown’s plan, the DJJ population would experience an estimated increase of 49 youths during fiscal year 2018-2019. The plan would cost $3.8 million and create 25.6 new positions during the first year, increasing to $9.2 million annually and 67.8 positions by 2020-2021.

According to CJCJ’s Washburn, extending the age of jurisdiction may unintentionally result in judges sending more kids to adult court. “When the age of jurisdiction was lowered in fiscal year 2012-13, the percentage of judicial transfer hearings that resulted in adult court prosecution declined,” Washburn said. “In the three years preceding the reform (2009-2011), an average of 75 percent of hearings resulted in a transfer to adult court, compared to 62 percent in the three years following (2013-2015).”

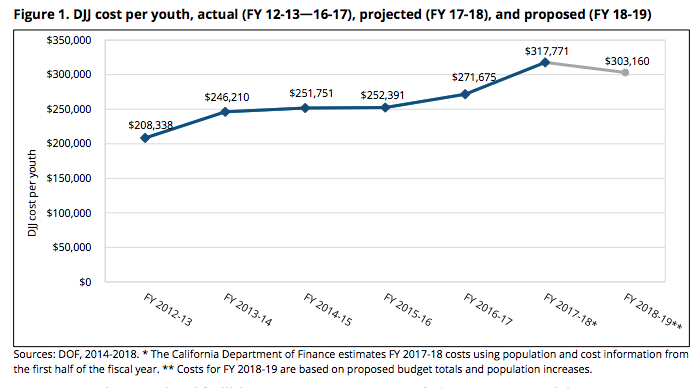

This week, Wasburn published a fact sheet that looks at the state’s rising juvenile incarceration costs.

According to the fact sheet, Brown’s budget has grown for the last three years, while the number of kids locked up in state detention facilities has dropped consistently for the last six years. Currently, the state lockups are sitting two-thirds empty.

There were an average of 624 youth in state juvenile facilities on any given day in January.

And the cost of spending per locked up youth is expected to hit an all-time high of $317,771 by the end of the current fiscal year—more than $65,000 higher than the state’s previous budget estimates for the year. The jump can be traced back to the fact that the state locked up fewer kids this year than initially expected, according to the CJCJ fact sheet.

What about outcomes?

Washburn points out that the DJJ’s current model does not appear to be working for youth. Youth recidivism remains a serious problem for the state. According to the latest California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation data, 74.2 percent of youth released from DJJ custody have been rearrested 53.8 percent have been reconvicted. A total of 37.3 percent of youth were sent back to state custody within three years.

The LAO, in its report, also expresses concern that while the DJJ has, in recent years, improved conditions and implemented programs that worked in other jurisdictions, the state has not been conducting appropriate evaluations of these programs to ensure that they are working as intended.

“DJJ has not completed an evaluation of the actual effect of its programs on youth,” the report states. “While DJJ is in the process of contracting for such an evaluation, this evaluation will not be released until the end of 2019-20. Accordingly, it remains unclear how effective DJJ’s program will be at rehabilitating additional youths that would be sent to DJJ under the Governor’s proposal.”

In the end, however, the LAO recommends that state legislators approve the governor’s plan, with caveats. The report recommends a sunset date for these changes to be put in place. “This would allow sufficient time for the proposed changes to be implemented and for the Legislature to determine whether they should continue,” the analysts write. Evaluation reports, too, “would allow the Legislature to monitor DJJ’s overall rehabilitation programs and provide some insight into the merit of the proposed age of jurisdiction changes,” according to the report.

Finally, the Legislative Analyst’s Office recommends tweaking the governor’s raise-the-age plan.

“Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature provide juvenile court judges who are conducting transfer hearings the discretion to allow a youth to remain in DJJ up to the age of 25 in cases where a judge determines that not doing so would necessitate that the youth be transferred to adult court,” the report says.

“This would provide an alternative to sending such youth to adult court without resulting in other juvenile court youths remaining in DJJ beyond their 23rd birthday unnecessarily.”