Despite an ongoing national movement toward banning solitary confinement for youth, which has been revealed to be counterproductive and harmful, isolation is still a common fixture in juvenile facilities, and it disproportionately affects kids of color and LGBTQ youth, according to research laid out in a Juvenile Law Center (JLC) report. JLC is a public interest law firm focused on improving the juvenile and foster care systems.

The report, released Wednesday, includes information from surveys of public defenders, as well as interviews with correctional administrators and justice system-involved kids and their families.

The report defines solitary confinement (or room confinement) as “involuntary restriction of a youth alone in a cell, room, or other area for any reason other than a temporary response when youth behavior presents an immediate risk of physical harm.”

Research shows that teenagers are fundamentally different from adults, and teens’ brains continue developing into adulthood. Moreover, solitary often has a devastating impact on the mental health of children and teens (and adults), many of whom have experienced childhood traumas. Solitary often exacerbates mental illness, and can create disorders and suicidal ideations where there weren’t any before. According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 50 percent of locked up youth who commit suicide do so while in solitary confinement.

People of color, overrepresented at every point of the criminal justice system, are also at a heightened risk of being stuck in solitary. Limited data suggests that Black and Latinx individuals also spend longer periods of time in isolation than the general prison population.

So, too, are LGBTQ kids overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. The report points to another study that revealed that while only .6% of people in adult correctional facilities are transgender, they comprise 7.3% of the population held in solitary. LGBTQ people—especially transgender people—are often placed in isolation as a form of protection, despite the well-documented harms caused by confinement.

Eddie Ellis, founder of One by 1, a nonprofit that works to prevent youth incarceration and to support juvenile justice system-involved kids, said that when he was released from lockup, he started having panic attacks, and later, as an adult, doctors diagnosed him with PTSD. “I still deal with it,” Ellis said. “I confine myself to my room a lot.”

According to 2016 data from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, nearly half of juvenile facilities reported that they control kids’ behavior with stints in isolation that last more than four hours. In states and local jurisdictions that have reformed their use of isolation, four hours is the standard maximum for isolating a child.

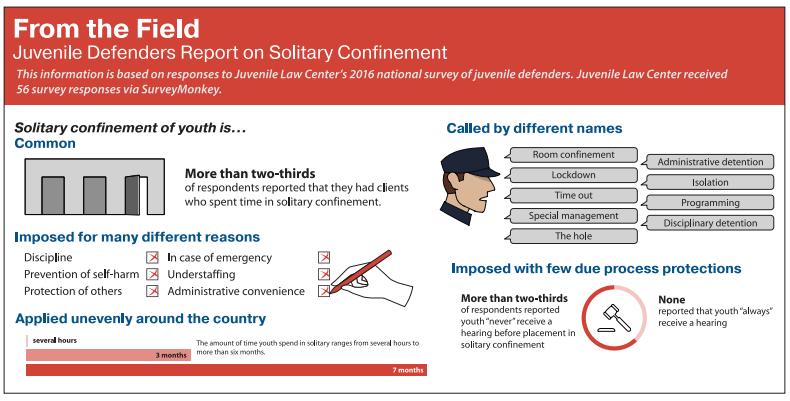

And of the 56 juvenile public defenders across the nation that JLC surveyed, more than two-thirds reported that they have young clients who have been held in solitary confinement. The defenders said that youth are isolated as punishment, in order to protect youth or others, and for administrative reasons (like while a child is processed into a new facility).

The public defenders reported that their clients’ time in solitary ranged from several hours to as long as seven months. More than two-thirds of the respondents also told JLC that kids “never” receive a hearing before corrections officers put them in solitary.

And once in isolation, defenders reported that kids often go without basic necessities like mattresses, sheets, showers, eating utensils, and mental health care.

Kids in solitary often also miss out on the educational opportunities given to their peers.

One young person told JLC that after he was placed in a tiny isolation cell, “[all I got was] a little bitty bed mat, a dirty blanket, a towel, a little bitty bar of soap…I had to hand wash my boxers just to have them clean.”

Another person who experienced isolation while in a juvenile facility told JLC that she was left alone for a week without a shower or a change of clothes.

“I didn’t know what was going to happen. I kept thinking ‘what if I get lost in the system in here,'” a youth identified as C.H. said. “I thought they had forgot about me…It’s like you’re sitting there wondering ‘what if they forget about me in this cell, I’ve been in here for days.’”

Solitary Reform Across the Nation

Former President Barack Obama barred federal prisons from putting juveniles in solitary in 2016.

The same year, Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 1143, a law that blocks guards from using isolation either as a punishment, for convenience’s sake, or to coerce kids. It also limits “room confinement” to a maximum of four hours at a time. Thanks to the 2016 law, confinement only becomes an option after other, less restrictive options are exhausted (except when using those alternatives would put kids or staff in danger). At the local level, the LA County Board of Supervisors banned solitary for youth in all 16 juvenile detention facilities in May of 2016.

A number of other states, including Massachusetts, Colorado, and New York have passed laws in recent years limiting the use of solitary in the juvenile justice system.

In 2014, as part of a settlement with the US Department of Justice, the state of Ohio agreed to ban the use of solitary for minors in custody, after the DOJ found the corrections staff to be excessively isolating kids with mental illness.

Instead of isolating, Ohio ramped up the activities offered to locked up youth, adding more visiting hours, religious services, apprenticeship programs, a parenting class, life skills courses, increased educational offerings, and reward events like movie nights, football games, and guest speakers.

“Our biggest effort was to get our staff to treat these kids like they are our kids. Once they did that, it got embedded in what we do every day, and that has been a game-changer,” said Harvey J. Reed, Director of the Ohio Department of Youth Services.

Between 2014 and 2015, use of solitary was reduced by 88.6 percent, and at the same time, violence in lockups dropped by over 20 percent.

But not every state is joining the movement away from harmful isolation. In one South Carolina facility, up to 20 percent of children are held in solitary, according to the report. And in Colorado, despite legislative reform, the CO Division of Youth Corrections reportedly is still relying on solitary confinement.

JLC Recommends

Based on the surveys, as well as information gathered from corrections workers and youth, JLC put together a list of 11 recommended areas for reform.

The most obvious reform action JLC recommends is ensuring that solitary confinement is banned for all reasons other than to protect kids and staff from immediate danger. Even then, JLC says there must be “clear limits” to the use of isolation in emergency situations.

The report also made clear that while the recommendations focus on policies and practices within juvenile lockups, “the most effective way to end the practice is to keep youth at home with their families and in their communities, providing quality supports and services when necessary.”

JLC offers recommended litigation strategies that could be helpful to bring about reforms, including bringing claims challenging governments’ failures to provide kids with education while they’re in solitary.

The report urges public defenders to visit their clients in their facilities, so that they can better advocate for youth. And kids should always have post-disposition representation, as most often, kids are isolated after they’ve been adjudicated, the report says.

Advocates should also file complaints about the use of solitary confinement when it violates a facility’s policy, according to JLC.

Community partnerships between families, kids, and advocates are also crucial, as they can directly impact efforts to reform the juvenile justice system, by bringing abuses to the attention of public defenders, policy reform advocates, litigators, and lawmakers.

“I would tell a legislator—think about these kids’ futures,” said Eddie Ellis. “You may be really destroying these kids emotionally and mentally before they have a chance to mature as people. Some of these kids may not be able to recover. These experiences are very detrimental to…these kids, and to the community.”