From 2000 to 2016, the United States’ use of controversial for-profit prisons to lock up inmates increased by nearly half, according to a new report by The Sentencing Project called “Capitalizing on Mass Incarceration.” During a similar period, between 2002 and 2017, the number of immigrant detainees in private prisons soared 442 percent.

In 2016, there were 128,063 prisoners—or 8.5 percent of the state and federal prison populations—housed in private prisons, an increase of 47 percent over 2000, when there were 87,369 in the facilities. In comparison, the overall prison population rose by 9 percent during those years—one-fifth of the rate of for-profit prison populations.

The private prison population more than doubled in six states during those years, and the federal government increased its use of private prisons by 120 percent.

These ballooning detainee and prisoner populations are sent to facilities run by companies plagued by scandals, that enjoy limited oversight, according to the report.

The two largest private prison companies, GEO Group and CoreCivic (formerly Corrections Corporation of America), had combined revenues of $3.5 billion in 2015,

Texas had the largest population of state prisoners housed in private prisons–13,692. The state was the first to make use of for-profit lockups in 1985.

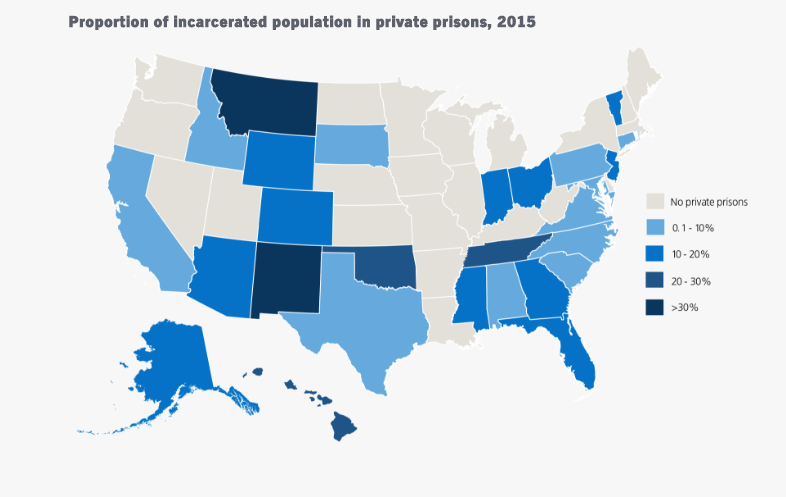

As of 2016, a total of 23 states, including Missouri, New York, Oregon, and Washington, did not use any private prisons. Four of the other 27 states locked up less than one percent of their inmates in for-profit facilities. At the other end of the spectrum, Montana and New Mexico, sent 38.8 and 43.1 percent of their state prison population to private prisons, respectively.

In 2016, California had 5.4 percent of its prison population (7,005 people) in private facilities—a number 54.1 percent higher than in 2000.

Texas had the largest population of state prisoners housed in private prisons–13,692. The state was the first to make use of for-profit lockups in 1985.

Eight states, including Arkansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Nevada, and Utah, ended their use of for-profit prisons between 2000 and 2016, citing concerns about safety and cost.

Fives states that, in 2000, did not employ private lockups, started using them by 2016. These states were Alabama, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Vermont.

And many states ship their inmates to far-flung, out-of-state facilities.

California and Idaho send inmates to private prisons in Colorado, Oklahoma, and Mississippi, while Hawaii forces the families of inmates to spend hundreds (sometimes thousands) of dollars on travel, in order to see their loved ones locked up thousands of miles away in Arizona.

The Feds

The federal government is private prisons’ most lucrative client.

Between 2000 and 2016, the federal government increased its private prison population by 120 percent—from 15,524 people to 34,159, or 18.1 percent of the feds’ total prison pop.

Approximately 37 percent of the federal total for-profit prison population are in halfway houses or are on home confinement, according to The Sentencing Project.

The report notes that in recent years, the U.S. government reduced its use of private facilities for federal inmates, as overall federal prison populations dropped via sentencing reform.

However, in 2017, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions rolled back an Obama-era directive to phase out the use of for-profit prisons, despite the fact that an Office of the Inspector General review found that private prisons were more dangerous than U.S. Bureau of Prisons-run lockups for both guards and inmates.

AG Sessions followed up his reversal of Obama’s initiative by ordering prosecutors to seek the most serious charges and sentences possible for federal cases.

The Immigrant Detention Cash Cow

The federal government’s population of immigrant detainees locked in private prisons grew an astounding 442 percent, to 26,249 immigrants, between 2002 and 2017. In fact, 73 percent of all locked up immigrants facing deportation were locked up in for-profit prisons.

Immigrant detention increased dramatically under the Obama administration. In 2009, Congress imposed an immigrant lock-up quota that tied Department of Homeland Security funding to paying for 33,400 immigration detention beds, even if there weren’t that many people to detain. The number rose to 34,000 in 2013, as an influx of people fleeing violence in Central America crossed the border into the U.S.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement reports that the government is now arresting and locking up 40 percent more immigrants than in mid-2017. In order to keep up with the arrests, President Donald Trump asked Congress to approve $1.2 billion in the 2018 budget for 15,000 more beds in private prisons.

Private Prison Myths

GEO Group and CoreCivic purport to save states and the federal government money, while treating prisoners like commodities, even employing lock-up quotas and “low crime taxes” that demand payments for empty prison beds.

The two companies have spent tens of millions of dollars in the last three decades lobbying and funding the campaigns of private-prison-friendly candidates.

And research has revealed that using private prisons may not actually save states money on incarceration costs.

In 2010, Arizona, a state with cost-savings requirements for contracting with private prisons, found that the state did not save any money by contracting out minimum-security prison beds, and even lost money by using private prisons, rather than publicly run facilities, for medium security beds.

And in 1996, the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) concluded that the current body of research on the costs of private prisons did not “offer substantial evidence that savings have occurred.” In 2009, University of Utah researchers found, too, that “prison privatization provides neither a clear advantage nor disadvantage compared to publicly managed prisons.”

Additionally, all the cost-cutting promises create poor conditions within the facilities, and lead private prison companies to skimp on staffing levels, salary, and training—factors that researchers say increase safety risks.

The report calls on states and the federal government to “reexamine” their use of private prison companies.

“The complications of mass incarceration that include the fracturing of low-income communities of color, the mistreatment of incarcerated people and the subjugation of people with criminal records cannot be wholly laid at the feet of private prison corporations,” the study concludes. “Over several decades, public institutions and lawmakers, with public consent, implemented policies that led to mass incarceration and the collateral consequences that followed. But private prisons have capitalized on the chaos of this policy approach and have worked to sustain it.”

States and the feds should phase out the use of private prison corporations, increase oversight and require more robust transparency from the companies, stop sending prisoners out-of-state, and eliminate the federal immigrant bed quota, the report says.