A new 146-page report digs into what Los Angeles County must do, and what it will cost, to get ready for the final shuttering of the dangerous and dilapidated Men’s Central Jail.

The deeply researched report drills into the ways the county will need to significantly expand its community-based system of care, increase diversion efforts, and move the MCJ population that remains into other jail facilities before the jail can be closed.

For those unfamiliar, in August 2019, the LA County Board of Supervisors made the historic decision to cancel a $1.7 billion contract to replace the dangerous and dungeon-like Men’s Central Jail, and to commit that money and effort to a “care first, jail last” ethic, instead. The decision came after years of pressure from advocates and community members.

Last July, a motion from LA County’s supervisors called for the creation of a workgroup — the Men’s Central Jail Closure Workgroup — made up of the Office of Diversion and Reentry, members of the LA County Sheriff’s Department, representatives from other county departments, along with community stakeholders and service providers. The group was directed to return to the board with plans for closing MCJ within a year.

The workgroup’s final report, released on Tuesday, March 30, after more than eight months of work, lays out a possible path for closing MCJ not in the originally hoped-for 12 months, but in 18-24 months.

Community Groups Call for Jail Closure and a Fully Funded Measure J

Meanwhile, on Monday, March 29, the day before the jail closure report was delivered, community members — led by the JusticeLA coalition, ReimagineLA, Black Lives Matter-LA, and Dignity & Power Now, among others — gathered outside the Kenneth Hahn Hall of Administration and Men’s Central Jail to call on county leaders to close the jail and fully fund Measure J.

LA County residents approved Measure J last November, amending the county charter to permanently set aside at least 10% of existing locally-controlled revenues to be directed to community investment and alternatives to incarceration starting in fiscal year 2021-22. Last year, the county CEO’s Office estimated that the allocation could amount to between $360 and $490 million per year.

On March 16, 2021, LA County CEO Fesia Davenport sent a memo to the county supervisors proposing that LA set aside $100 million for Measure J’s first year of implementation, a far cry from the verbal estimate by previous CEO Sachi Hamai, of between $360 and $490 million annually.

The CEO’s budget team is basing its March estimate on the current fiscal year’s unrestricted revenues in the general fund, which amount to about $3 billion, ten percent of which would be $300 million.

The county technically has three years to work up to setting aside a full ten percent for Measure J. Thus, the CEO proposed that the county start with a “down payment” of $100 million and build up to $300 million by the third year of funding.

Davenport’s office also stressed to WitnessLA that, until the March 16 memo, “the CEO has never issued a written estimate about the set aside amount.”

“This is an ongoing process and all estimates are preliminary,” the communications department told WLA. “The allocations will be determined by the Board of Supervisors, with input from the Measure J Advisory Committee, the CEO and County departments.”

The board of supervisors will hold public hearings in May to get input on the budget before its finalization in June.

Advocates in the community are calling on county leaders to fully fund Measure J in its first year, rather than waiting until year three.

“The CEO’s having trouble finding some money,” Mark-Anthony Clayton-Johnson of Dignity & Power Now said to those gathered on Monday. “She says she wants to give $100 million to Measure J. We want to help her find some money.”

The county, said Clayton-Johnson, spent $84 million on the sheriff’s department’s litigation fees and settlements last year. The county also spent $46 million arresting and booking unhoused black people for public health-related offenses, quality of life crimes, and probation violations, he said. Money spent propping up the county’s broken justice system should be spent on building up the community instead, according to Clayton-Johnson and fellow justice advocates.

The Winding & Complicated Route to MCJ Closure

On a separate but parallel track to that of the Men’s Central Jail Closure Workgroup , various Measure J subcommittees spent five weeks developing recommendations for implementing Measure J, including a recommendation that the county allocate $200 million in the first year to expand housing and service beds for at least 3,600 people currently incarcerated as well as for members of communities heavily affected by the criminal legal system, COVID-19, inadequate public health services, and poverty.

In addition, during a recent public safety budget meeting hosted by the civilian commission overseeing the sheriff’s department on April 1, Dr. Jon Sherin, head of the LA County Department of Mental Health, said the county needs to vastly expand mental health crisis response teams and the number of available treatment beds for people with mental illness.

“In my humble opinion we have about 20 to 25 percent of the capacity we need to properly respond with any type of timeliness to mental health, behavioral health emergencies in our communities,” said Dr. Sherin.

Los Angeles has “about 4,000 treatment beds in LA County, and we’re about 4,000 treatment beds short,” Sherin said. “When we think back to the ’60s and we think back to de-institutionalization, and we think about the fact that we have an open asylum on the street and a closed asylum in the jail, we need to really step forward with treatment and care, and making sure that people have access to care.”

Tuesday’s report addresses these and other needs that must be met to achieve a “care first, jail last” model in LA.

The jail closure report is broken into three parts: a Community Plan for expanding community-based care, a Diversion Plan, and a Facilities Plan for moving some incarcerated people into the county’s other jails. The diversion plan looks at how to divert around 4,500 people — mostly people with serious mental health needs, medical needs, or substance use needs — from LA’s jails.

To achieve this level of diversion, the Community Plan includes the addition of 3,600 community-based mental health care beds and approximately 400 more beds for people with medical needs, substance use disorder needs, and/or housing needs, within that 18-24 month period. The county already has several successful programs, through the Office of Diversion and Reentry, the Department of Mental Health, and other county agencies, that could be scaled up to serve an additional 4,000 people. More beds should be added during the third year, the report says, to sustain the jail population reduction and jail closure.

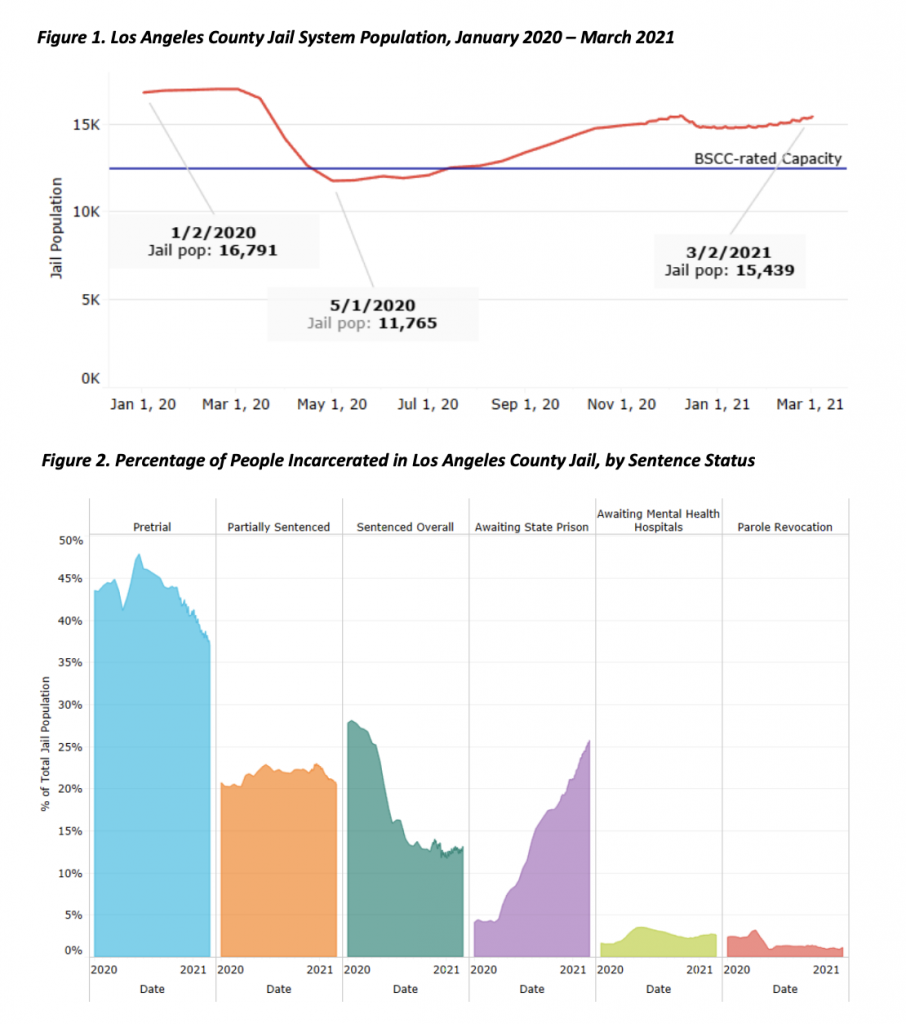

Between March and October 2020, county criminal justice system leaders worked together to reduce the jail population, which had hovered around 17,000 across the county’s jail facilities. By May 1, 2020, there were 11,765 people in jail.

In recent months, however, that number began creeping back toward pre-COVID numbers.

By March 2, 2021, the jail population had reached 15,439 people. Now, as has been the case historically, the largest portion of the jail population has consisted of people held pretrial.

For the jail closure to be possible, the county must reduce its total jail population by at least 30 percent.

To do this, county justice leaders will have to increase early releases and pretrial releases, while addressing racial disparities in current practices.

The county’s pretrial release and early release protocols amid the pandemic resulted in higher release rates for white incarcerated people than their Black and Latinx peers, “implying that race-neutral release approaches do not promote equity but rather perpetuate systemic racism,” the report said.

The county can either divert or otherwise decrease custody time for people who spend more than 30 days in jail, as short jail stays make up just six percent of the average daily jail population.

“By contrast, people who spend more than 100 days in custody — most of whom have serious felony cases — fill 71 percent of the jail beds daily,” the report said. People with longer jail stays must be included in early release and diversion strategies.

“While some jurisdictions across the country have tried tackling reforms by tepidly tinkering with policies and piloting programs for only the most minor charges,” according to the report, “closing MCJ will require Los Angeles County to be bolder and change the status quo, including for felony cases.”

What Comes Next

The report delivered last Tuesday, March 30, will be followed by a series of related reports to be released over the next two months. The supervisors will use these additional reports to inform their decisions regarding the jail’s planned closure.

They include a report from the Gender Responsive Advisory Committee on improving care for justice-involved women and gender-expansive people, a report on jail population reduction strategies from the Jail Population Review Council, a financial analysis and population projection from the JFA Institute, a report with recommendations on how to spend Measure J money from the Measure J Advisory Group, and finally an update on diversion work from the Alternatives to Incarceration Initiative.

On Tuesday, LA County Supervisor Hilda Solis expressed gratitude toward the workgroup for its work on the jail closure report, noting that it would “not only help us close Men’s Central Jail but examine all the structures that play a role in the systemic incarceration of people of color in LA County.”

Using this and the other upcoming reports, she said, would allow county officials “to piece together all of the recommendations and strategies to create policies, programs, and services” to reduce the flow of people into the jails, and to “implement a holistic plan that will address the core, systemic issues that lead to mass incarceration including a lack of mental care and health services, housing, job stability, and other public services.”

Supervisors Hilda Solis and Sheila Kuehl will next introduce a motion to convene an “implementation team” to review all the information and recommendations in the reports, and to plan the county’s next steps toward jail closure.

The supes have plans for a second motion that will create a fund for expenses related to the demolition of the jail, upgrades for LA’s other jails, and expanding alternatives to incarceration. The money will come from a pot of cash formerly intended to build a new mental health treatment facility (a jail by another name) to replace Men’s Central Jail, and a women’s jail, the plans for which have also since been canceled.

The supervisors also want to “explore the use of one-time federal funds through the American Rescue Plan to reserve $237 million” for approximately 3,000 community care beds and to expand other programs meant to reduce incarceration.