By Miriam Aroni Krinsky, Marcy Mistrett and Karl Racine

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Over the last few years, evidence-based reforms at the local, state, and national level have endeavored to reverse some of the harmful laws and policies that emerged during the tough-on-crime decades.

Last week, a reauthorization of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act cleared a legislative hurdle on its path to final approval. (The JJDPA was first enacted in 1974 and hasn’t been successfully revamped and reauthorized since 2002.)

The JJDPA gave states funding for compliance with these four requirements: do not detain kids for status offenses, work to reduce disparate minority contact with the justice system, keep kids out of adult facilities (with a few exceptions), and when kids do have to be kept in adult lock-ups, keep them “sight and sound” separated from adults.

In California, the 2016 voter-approved Proposition 57 removed the power to transfer kids to adult court from the hands of prosecutors, and gave the control back to judges.

That same year, then-President Barack Obama barred federal prisons from putting juveniles in solitary confinement.

This year both New York and North Carolina raised the age of criminal responsibility—when juveniles are automatically tried as adults—from 16 to 18 years old. They were the last two holdout states.

These are just some of the noteworthy reforms that acknowledge that kids and teens are fundamentally different from adults, and that have, in recent years, worked to improve the juvenile justice system and youth outcomes across the nation.

In the essay below, Miriam Krinsky, a former Assistant US Attorney (now Executive Director of Fair and Just Prosecution), Marcy Mistrett, CEO at the Campaign for Youth Justice, and Karl Racine, the District of Columbia’s Attorney General, argue that while we have come a long way toward reforming the system to better serve youth, there are still glaring disparities and inadequacies that must be addressed, and “we have miles to go before we sleep.”

-Taylor Walker

Dakota County, Minnesota, prosecutor James Backstrom, in his July 28 opinion piece, “America’s Juvenile Justice System is Appropriately Balanced,” affirmed many of the strongest arguments for ongoing juvenile justice reform. He recognized that “youth are fundamentally different from adults” and acknowledged that “[w]e now know that the human brain is not fully developed until the early twenties.”

Backstrom also noted that the National District Attorneys Association “supports a balanced approach to juvenile justice which properly takes into consideration all relevant factors in deciding what criminal charge should be filed against a juvenile offender.” These views reflect important research and corresponding positive movement by prosecutors in recent years.

Where we respectfully part company with Backstrom, however, is in his conclusion: That our work to reform the juvenile justice system is complete and that current practices for juveniles in the justice system are properly balanced.

In the wake of “tough-on-crime” prosecutorial enhancements in the 1980s and 1990s, many prosecutors began exploring the benefits of smart-on-crime juvenile justice reforms. Those reforms have dramatically reduced the number of youths in the adult system while educating judges, prosecutors, and public defenders on the unique needs and challenges of justice-involved youth. These research-based reforms are responsible for positive changes to the system—changes that the Campaign for Youth Justice and other groups have sought to advance for decades.

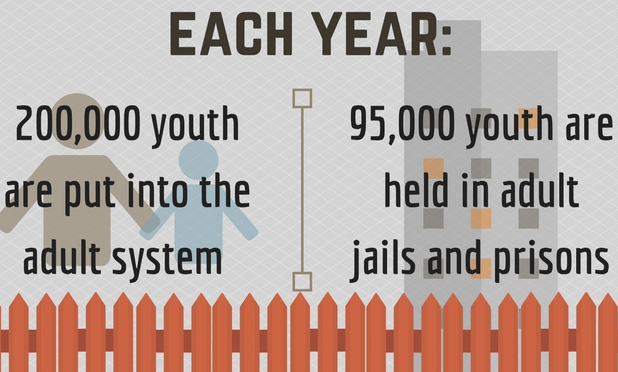

In 2007, there were an estimated 250,000 youths prosecuted as adults in the United States. The vast majority ended up in adult court because their state had an age of criminal responsibility below 18. Since then, nine states have passed legislation to raise that age to 18. According to a recent report by the Justice Policy Institute, after the first five states raised the age, the number of youth prosecuted as adults dropped by nearly half—even while youth crime fell. Recently, four additional states have passed legislation that will cut the number of youth automatically prosecuted as adults in half once again.

In addition to reforms raising the age of criminal responsibility, states have removed youth from adult jails and prisons, limited the pathways of transfer from juvenile to adult systems, and restored judicial discretion by limiting or eliminating prosecutors’ role in transferring youth to the adult system.

States that have instituted evidence-based, developmentally appropriate juvenile justice systems have seen their costs, confinement, and youth crime rates fall even faster than the national average.

States have not made these decisions in a vacuum. As cited in Backstrom’s piece, the U.S. Supreme Court has held that children are different than adults, and that these differences need to be taken into account. Indeed, the U.S. Department of Justice’s National Task Force on Children Exposed to Violence unambiguously recommended that prosecutors, “[w]henever possible, prosecute young offenders in the juvenile justice system instead of transferring their cases to adult courts.”

Research from across the country has universally concluded that youth prosecuted as adults are more—not less—likely to recidivate than youth who remain in the juvenile justice system. Further, they recidivate quicker, and through the commission of more serious offenses.

The more enlightened juvenile justice system Backstrom recounts in his opinion piece is not a reflection of the tough-on-crime laws of the 1980s, but rather the research-based juvenile justice reforms that have resulted in nearly 70 new laws in 36 states and the District of Columbia since 2005. These laws have been passed by bipartisan state legislatures, frequently endorsed by law enforcement, and signed into law by both Republican and Democratic governors.

While these recent reforms are significant, we believe that we are nowhere near the stopping point in juvenile justice reform that Backstrom believes we have reached. Being smart on juvenile justice requires continued use of research and evidence to improve outcomes for youth. It means mourning the youths in Texas and Louisiana who committed suicide while being held in adult jails. It means fighting to block cases like the 10-year-old who was charged as an adult in Pennsylvania, and the two 12-year-olds who were arrested in 2014 and who are still are being tried and treated as adults in Wisconsin.

In every state and the District of Columbia, there are still multiple mechanisms that drive youth into the adult system or lock them away in adult facilities. There are still laws that exclude youth accused of “violent crimes” from the programming and supports of the juvenile justice system, even while the vast majority of these youth return to their communities in their early to mid-twenties without the benefit of evidence-based rehabilitative services.

Our system is not balanced if research continues to show that youth of color, particularly black males, are not only more likely to be prosecuted as adults, but more likely to receive harsher sentences than their peers. Our system cannot be deemed just or adequately focused on rehabilitation if we still give 15-year-olds 15-year sentences, or even life without parole—a sentence that still remains in place despite the Supreme Court rulings that require reconsideration of these cases.

In recent years, we’ve come a long way in making our juvenile justice system “appropriately balanced,” and we should all applaud efforts by Backstrom and others to advance these changes. However, if our collective responsibility is to foster justice and public safety—as we believe it is—we have miles to go before we sleep. Our young people, and our communities, deserve no less.

This piece was originally published in Route Fifty, a digital news publication that connects the people and ideas advancing state, county and municipal government across the United States.

Miriam Aroni Krinsky spent fifteen years as a federal prosecutor and is the Executive Director of Fair and Just Prosecution, a national network of elected prosecutors committed to new thinking and innovation.

Marcy Mistrett is the CEO at the Campaign for Youth Justice, a national initiative focused on ending the prosecution, sentencing and incarceration of youth under age 18 in the adult criminal justice system.

Karl Racine currently serves as the first elected Attorney General in the District of Columbia. His duties include serving as the District’s chief prosecutor for juvenile crimes.

Image: Campaign for Youth Justice