By Peter Wagner and Emily Widra, Prison Policy Initiative

The United States incarcerates a greater share of its population than any other nation in the world, so it is urgent that policymakers think about how a viral pandemic would impact people in prisons, in jails, on probation, and on parole, and to take seriously the public health case for criminal justice reform.

Below, we offer five examples of common-sense policies that could slow the spread of the virus. This is not an exhaustive list, but a first step for governors and other state-level leaders to engage today, to be followed by further much-needed changes tomorrow.

Quick action is necessary for two reasons: the justice-involved population disproportionately has health conditions that make them more vulnerable, and making policy changes requires staffing resources that will be unavailable if a pandemic hits.

The incarcerated and justice-involved populations contain a number of groups that may be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, the novel coronavirus. Protecting vulnerable people would improve outcomes for them, reduce the burden on the health care system, protect essential correctional staff from illness, and slow the spread of the disease.

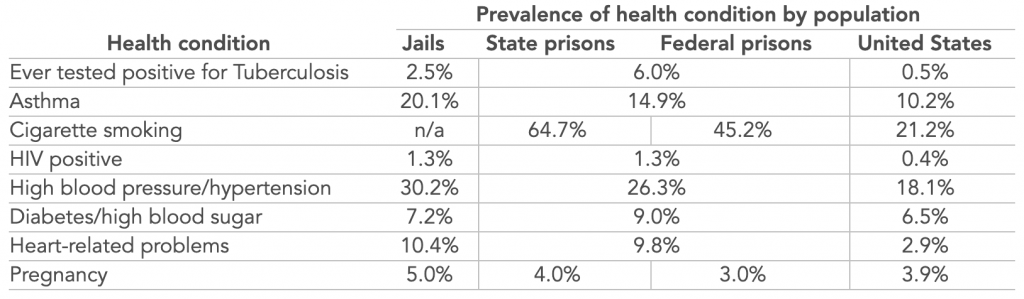

Health conditions that make respiratory diseases like COVID-19 more dangerous are far more common in the incarcerated population than in the general U.S. population. Pregnancy data come from our report, Prisons neglect pregnant women in their healthcare policies, the CDC’s 2010 Pregnancy Rates Among U.S. Women, and data from the 2010 Census. Cigarette smoking data are from a 2016 study, Cigarette smoking among inmates by race/ethnicity, and all other data are from the 2015 BJS report, Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12, which does not offer separate data for the federal and state prison populations. Cigarette smoking may be part of the explanation of the higher fatality rate in China among men, who are far more likely to smoke than women.

The other reason to move quickly is that, on a good day, establishing and implementing new policies and practices is something that the government finds challenging to do on top of its other duties. If a pandemic hits and up to 40% of government lawyers are either sick or taking care of sick relatives and most of the rest are working from home, making policy change is going to be much harder and take far longer. If the government wants to protect both justice-involved people and their already overstretched justice system staff from getting the virus and spreading it further, they need to act now.

Here are five places to start:

- Release medically fragile and older adults. Jails and prisons house large numbers of people with chronic illnesses and complex medical needs, who are more vulnerable to becoming seriously ill and requiring more medical care with COVID-19. And the growing number of older adults in prisons are at higher risk for serious complications from a viral infection like COVID-19. Releasing these vulnerable groups from prison and jail will reduce the need to provide complex medical care or transfers to hospitals when staff will be stretched thin. (In Iran, where the virus has been spreading for several weeks longer than in the U.S., the government just gave temporary release to almost a quarter of their total prison population.) 1

- Stop charging medical co-pays in prison. Most prison systems have a short-sighted policy that discourages sick people from seeking care: charging the free-world equivalent of hundreds of dollars in copays to see a doctor. In the context of COVID-19, not receiving immediate, appropriate medical care means allowing the virus to spread across a large number of people in a very confined space. These policies should all be repealed, but at a minimum should be immediately suspended until the threat of pandemic is over. (This will also reduce the administrative burden of processing and collecting these fees.)

- Lower jail admissions to reduce “jail churn.” About one-third of the people behind bars are in local jails, but because of the shorter length of stay in jails, more people churn through jails in a day than are admitted or released from state and federal prisons in 2 weeks. In Florida alone, more than 2,000 people are admitted and nearly as many are released from county jails each day. As we explained in a 2017 report, there are many ways for state leaders to reduce churn in local jails; for example, by: reclassifying misdemeanor offenses that do not threaten public safety into non-jailable offenses; using citations instead of arrests for all low-level crimes; and diverting as many people as possible people to community-based mental health and substance abuse treatment. State leaders should never forget that local jails are even less equipped to handle pandemics than state prisons, so it is even more important to reduce the burden of a potential pandemic on jails.

- Reduce unnecessary parole and probation meetings. People deemed “low risk” should not be required to spend hours traveling to, traveling from, and waiting in administrative buildings for brief meetings with their parole or probation officers. Consider discharging people who no longer need supervision from the supervision rolls and allow as many people as possible to check in by telephone.

- Eliminate parole and probation revocations for technical violations. In 2016, approximately 60,000 people were returned to state prison (and a larger number were arrested), not because they were convicted of a new criminal offense, but because of a technical violation of probation and parole rules, such as breaking curfew or failing a drug test. States should cease locking people up for behaviors that, for people not on parole or probation, would not warrant incarceration. Reducing these unnecessary incarcerations would reduce the risk of transmitting a virus between the facilities and the community, and vice versa.

There is one more thing that every pandemic plan needs to include: a commitment to continue finding ways — once this potential pandemic ends — to minimize the number of confined people and to improve conditions for those who are incarcerated, both in anticipation of the next pandemic and in recognition of the every day public health impact of incarceration.

None of the ideas in this briefing are new. All five are well established criminal justice reforms that some jurisdictions are already partially implementing and many more are considering. These ideas are not even new to the world of pandemic planning, as we found some of them buried in brief mentions in the resources listed below — albeit after many pages about the distribution of face masks and other technical matters. Correctional systems need to be able to distribute face masks to the people who need them, of course, but making urgent policy decisions about changing how and where you confine people is not something that should be relegated to a sentence about how agencies may want to “consider implementing alternative strategies.”

The real question is whether the criminal justice system and the political system to which it is accountable are willing to make hard decisions in the face of this potential pandemic, in the face of the one that will eventually follow, and in the context of the many public health costs of our current system of extreme punishment and over-incarceration.

Appendix: Other resources for practitioners

While preparing this briefing, the Prison Policy Initiative identified some resources that may be helpful for facilities and systems that may be starting from scratch on a COVID-19 response plan, which we share below. This list is not intended to be comprehensive, and will hopefully soon be out of date as other agencies update and share their own plans:

- Correctional facilities pandemic influenza planning checklist, CDC, September 2007 (This checklist is very helpful, but many of the links in the document are broken as of this publication. Presumably the CDC will update this soon.)

- Pandemic influenza and jail facilities and populations, Laura Maruschak, et. al., American Journal of Public Health, September 2009

- Pandemic influenza preparedness and response planning: guidelines for community corrections, Patricia Bancroft, American Probation and Parole Association, August 2009

- How public health and prisons can partner for pandemic influenza preparedness: A report from Georgia, Anne C. Spaulding, et al., April 2009

Footnotes

- Earlier this week, Iran reportedly released about 54,000 incarcerated people with sentences under five years, which is almost a quarter of their total prison population of 240,000 people, based on 2018 data from the World Prison Brief.

- Although national numbers of jail releases per day are not available, the number of jail admissions — 10.6 million annually — is relatively stable, with the jail population turning over quickly, at an average rate of 54% each week. Assuming, then, that the number of admissions is about the same as the number of releases, we estimate that about 29,000 people are released from jails in the U.S. every day (10.6 million divided by 365 days per year). In comparison, in 2017, state and federal prisons admitted and released over 600,000 people, averaging about 12,000 releases a week or 1,700 per day. For state-by-state data, we estimated the number of releases in a similar fashion — we divided the number of annual admissions and releases, obtained from the Census of Jails, 2013, by 365 days. Governors of other states may want to see this table based on data from the Census of Jails, 2013:

| State | Jail Admissions | Jail Releases |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 286,843 | 249,418 |

| Alaska | 5,392 | 3,686 |

| Arizona | 210,399 | 202,484 |

| Arkansas | 258,321 | 232,255 |

| California | 1,102,972 | 995,338 |

| Colorado | 211,397 | 197,866 |

| District of Columbia | 12,008 | 12,238 |

| Florida | 732,602 | 680,801 |

| Georgia | 602,648 | 537,857 |

| Idaho | 104,539 | 50,384 |

| Illinois | 315,553 | 290,264 |

| Indiana | 270,415 | 277,994 |

| Iowa | 127,179 | 123,693 |

| Kansas | 153,914 | 142,759 |

| Kentucky | 548,733 | 509,413 |

| Louisiana | 317,091 | 334,730 |

| Maine | 37,995 | 33,934 |

| Maryland | 156,659 | 164,736 |

| Massachusetts | 58,115 | 76,253 |

| Michigan | 359,631 | 348,584 |

| Minnesota | 188,662 | 180,393 |

| Mississippi | 125,961 | 119,682 |

| Missouri | 252,131 | 239,562 |

| Montana | 48,418 | 39,179 |

| Nebraska | 72,616 | 72,687 |

| Nevada | 144,256 | 146,657 |

| New Hampshire | 20,841 | 22,187 |

| New Jersey | 147,088 | 134,407 |

| New Mexico | 150,488 | 142,035 |

| New York | 219,320 | 201,939 |

| North Carolina | 417,199 | 433,700 |

| North Dakota | 39,367 | 35,979 |

| Ohio | 405,313 | 395,648 |

| Oklahoma | 409,293 | 261,454 |

| Oregon | 176,549 | 172,476 |

| Pennsylvania | 209,732 | 213,319 |

| South Carolina | 301,594 | 325,976 |

| South Dakota | 56,477 | 56,851 |

| Tennessee | 461,375 | 439,364 |

| Texas | 1,144,687 | 1,083,223 |

| Utah | 97,509 | 98,651 |

| Virginia | 355,549 | 304,466 |

| Washington | 283,627 | 305,963 |

| West Virginia | 47,439 | 46,210 |

| Wisconsin | 227,243 | 208,406 |

| Wyoming | 29,384 | 30,803 |

Peter Wagner is the executive director and Emily Widra is a research analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative, where this story first appeared.

Image by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

Oh…great…take advantage of tragedy, chaos and disorder and say what you really want….open the doors to all of the jails and prisons, and release all the prisoners into society. How convenient and revealing that some “far left think tank social engineering geniuses” had this plan waiting in the wings? Nice try…but no dice.

I guess if people criticize the President for wanting border security as a way to protect the people of this country, it should come as no surprise there are individuals working to take this country down from inside.

Oh…China…our “benevolent trading partner” is showing its true colors. They take no responsibility for the virus, feign moral outrage at the naming of the virus and threaten to nationalize all of our drug companies that so eagerly moved their manufacturing to the Communist (socialism in action) state.

Did you hear the ACLU just sent a letter to Sheriff AV asking for the release of inmates to prevent them from getting sick with the Coronavirus? Let’s just ignore the reason why these criminals are there in the first place I guess.

If the ACLU isn’t an organization bent on destroying civil society I don’t know what is.

@Conspiracy-The best part of that paragraph was the ACLU saying to let out the ones that dont pose a threat to society. I’m sorry but if you are in jail, you pose a threat to society.

Makes sense though.

Think about it….enemy you can’t see vs an enemy you can see. Much less panic.