A new report reveals that there are at least 428,000 so-called “frequent utilizers” — people who cycle in and out of local jails across the U.S. The number is reportedly the first national estimate of this population, which the report defines as people who go to jail three or more times in a 12-month period. The “frequent utilizers” are a subgroup of a larger population of people who return to jail: of the 4.9 million people booked into jails in 2017, at least 25 percent were rebooked into jail within that year.

The Prison Policy Initiative report, titled “Arrest, Release, Repeat,” shows that rate of multiple arrests increases significantly among people who are low-income or unemployed, have low educational achievement, or who have underlying health issues.

“4.9 million people go to jail every year — that’s a higher number than the populations of 24 U.S. states,” says Policy Analyst Alexi Jones, who co-authored the report with Senior Policy Analyst Wendy Sawyer. “But what’s even more troubling is that people who are jailed have high rates of economic and health problems, problems that local governments should not be addressing through incarceration.”

According to the report, just under half (49 percent) of people with more than one arrest within the year, had annual incomes below $10,000. By comparison, 36 percent of people arrested only once, and 21% of people with no arrests, had incomes that low. The unemployment rate jumps from 4 percent among people who were not booked into jail at all during the year, to 15 percent for people with two or more arrests and bookings during the year.

Incarceration rates are higher among people with lower educational attainment, the report shows. While 11 percent of people who were not jailed have no high school diploma, 20 percent of people with one jail booking, and 36 percent of people with two or more bookings had not completed high school.

Health troubles rise with the number of arrests per individual, as well. People with three or more arrests were more likely to have chronic health conditions and use emergency rooms multiple times over the 12-month period.

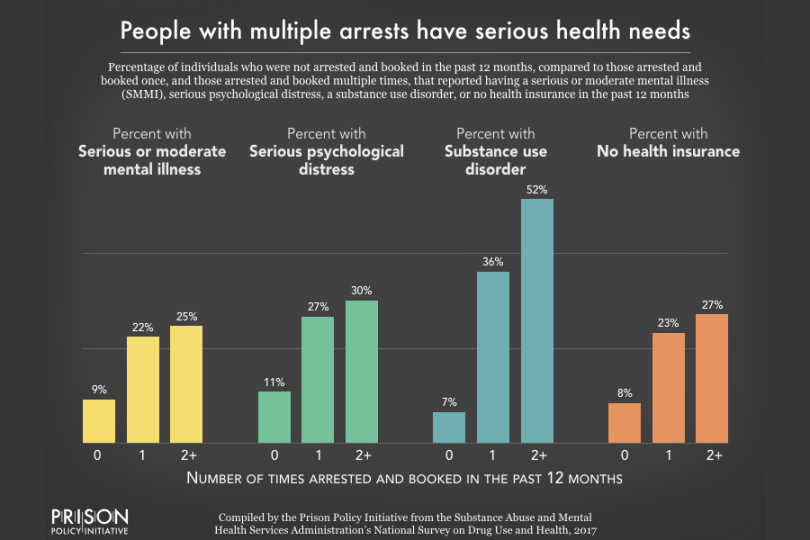

Additionally, 7 percent of the people with no jail time reported substance use disorders. That percentage jumps to 52 percent, for those with more than one stint in jail. The percentage of people with moderate or serious mental illness increases between these groups, as well, from 9 percent of people with no jail time to 25 percent for people with multiple trips to jail.

And the rate of health care access falls considerably lower as jail bookings increase. Only 8 percent of people with no incarceration were uninsured, while 23 percent and 27 percent of people with one jail booking or at least two bookings had no health coverage.

Black Americans also make up a disproportionate percentage of the population with multiple jail bookings, accounting for 21 percent of the people arrested once and 28 percent of the people with multiple arrests, despite comprising 13 percent of the national population.

Moreover, the majority of people arrested and jailed multiple times are accused of non-violent offenses. Approximately 88 percent of people booked into jail multiple times were not arrested for serious, violent crimes during the year Jones and Sawyer examined.

These “unnecessary arrests cost cities and counties millions of dollars but do nothing to fix the underlying medical, economic, and social problems, the report states.

County funds should be redirected away from building and expanding jails, and toward a series of alternatives to incarceration, including diversion, community interventions, sentencing reforms, and more.

Counties should increase the number of psychiatric beds available in health care facilities, the PPI report authors say. Long waitlists for mental health beds leave people who should be receiving intensive psychiatric care locked up in jails, instead.

The report also recommends more robust substance use and mental health treatment in the community. “Investing in such treatment is estimated to yield a $12 return for every $1 spent, as it reduces future crime, costly incarceration, and lowers health care expenses,” the report says.

These services must also be expanded within jails, and care in county lockups must be connected with those community services, so that care is not interrupted when people are released from jail, according to the report.

Jones and Sawyer also call for more diversion, including diversion that occurs before a person is arrested. The report suggests states pass legislation that downgrades certain misdemeanor offenses to non-jailable infractions. Citations would be preferable to arrests for some non-serious offenses, according to PPI, so that more people are able to wait for their court appearance at home, rather than in a cell (or after paying bail).

“Counties should stop using taxpayer dollars to repeatedly jail people,” says Sawyer, “and use the savings to fund public services that prevent justice involvement in the first place.”

Finally, Sawyer and Jones urge government agencies to collect and analyze data on the “frequent utilizer” population. “This data is crucial to understanding local frequent utilizer populations and designing effective, evidence-based interventions,” the report concludes.

“unnecessary arrests cost cities and counties millions of dollars but do nothing to fix the underlying medical, economic, and social problems, the report states”

More misleading studies. I am sure the victims felt the arrests were unnecessary also…