In the weeks leading up to a September 30 deadline, California Governor Gavin Newsom made final decisions on more than 1,000 bills.

As in previous years, we have put together a series of updates on some of the justice-related bills WitnessLA has been tracking this year, starting with bills addressing domestic violence and support for survivors.

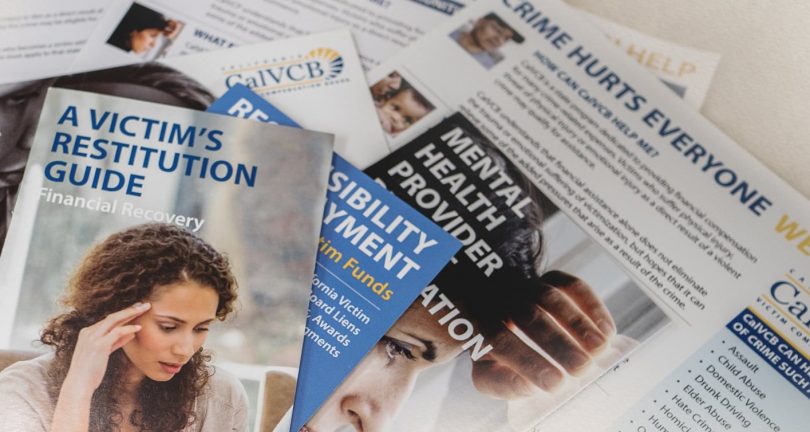

Among the newly signed bills was AB 2432, a bill to bolster the California Crime Victims Fund, which has long struggled to stay afloat.

The federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) distributes money to community-based organizations working with survivors in need, and to states for direct financial assistance for victims. Because the funding relies on fines and fees levied against people convicted of crimes, and is not supported by tax dollars, states are getting far less money deposited into their victim compensation funds than in years past.

Victim services in California received $87 million for fiscal year 2024 — a reduction of approximately 43% from the $153.8 million allocated the previous year, according to the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence.

AB 2432 seeks to make the California Victims Fund sustainable by establishing it in the State Treasury and by creating a new sentencing enhancement for corporations. Specifically, AB 2432 will establish a “corporate white collar criminal enhancement” through which a court can impose an additional fine on a corporation convicted of a misdemeanor or felony. That money will go into the California Crime Victims Fund. Courts will also be required to impose a separate restitution fine that would be split between the Crime Victims Fund and the prosecutor’s office.

The governor signed seven other bills alongside AB 2432, all focused on issues of domestic violence and support for survivors.

One of those bills, SB 690, extends the statute of limitations for domestic violence crimes from five years to seven years, starting in 2025.

Another bill is intended to increase the thoroughness of investigations when a person with a history of domestic violence victimization dies. The bill, SB 989, requires coroners to determine the circumstances, manner, and cause of death in cases when a person who commits suicide has experienced domestic violence.

Additionally, police will be required to interview families before making findings regarding a cause of death when the deceased has an identifiable history of domestic violence. In such cases, police will have authorization to request a complete autopsy.

The bill also requires the development of new guidelines for law enforcement around domestic violence and indicators that a suspicious death is a domestic-violence-related homicide.

SB 989 also gives family members access to photos and other media from an autopsy for use in civil action.

Another bill, AB 2422, will require the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation to publish online resources about the financial abuse that often accompanies physical abuse and other harm in cases of intimate partner violence.

One newly approved law means to shield people fleeing domestic violence from having their phone-connected cars tracked and manipulated by the person who caused them harm. SB 1394 addresses what Senator Dave Min (D-Irvine), the bill’s author, called a “potentially fatal problem” by requiring car manufacturers to terminate remote vehicle access if a person presents a dissolution decree, temporary order, or domestic violence restraining order that grants them “possession or exclusive use of the vehicle.”

A handful of other fresh laws are focused on issues related to protective orders.

AB 2308, extends the maximum duration of restraining orders against individuals convicted of certain domestic violence-related crimes from 10 years to 15 years. The bill also allows a prosecutor, defendant, or victim to petition to modify or terminate a restraining order for good cause, as long as all parties have 15 days notice before the hearing.

AB 2024, eliminates delays for minor errors in paperwork that often slow the process for obtaining domestic violence protective orders, which are supposed to be issued same-day or next-day.

The final bill, SB 554, clarifies that a person seeking to file a protective order does not need to be a resident of the state, but can file in any superior court in a county where the abuse occurred, where the defendant resides, where the petitioner resides or is temporarily located, or where a court otherwise has jurisdiction over the parties or the case.

So I’m a bit on edge, but in the end, it will be the women who saved democracy.

I’ve been stalked, he tracks my car, burglarizes and vandalized my home numerous times to where I’ve had my home completely gutted from a broken pipe he broke in my kitchen while I was I surgery for hip replacement. I’m a prisoner in my own home to afraid to leave for to long bc he and his family break in and steal, vandalize. They break my locks with bumper guns. Turn of my electricity to shut off security cams and system. The cops ignore me as do elderly abuse. He Terrorizes me and police do nothing for over 7 yrs now and no end in sight. I have pictures of my bruises body of when he plowed his truck into me and cops let him go, pics of my home completely destroyed by the flood he caused and many pictures of my numerous locks that he’s broken over the years of abuse. I’m 68 and need help so desperately with no one to turn to for help to end this.