By Teresa Wiltz

California this month became the first state to eliminate court costs, fees and fines for young offenders. But court officials and legislators wary of forfeiting a key source of revenue have raised roadblocks in states and localities that have tried to follow suit.

The Trump administration has further blunted momentum by scrapping an Obama-era warning against imposing excessive fees and fines on juveniles. Attorney General Jeff Sessions made the move as part of a broader effort to overhaul regulatory procedures at the Department of Justice. The administration declined to comment on whether it supports the imposition of such fees.

The state of Utah, the city of Philadelphia, and Johnson County, Kansas, are among the handful of jurisdictions that have scaled back juvenile fees and fines in the past year, but none has gone as far as California.

“It feels like a steep climb now,” said Joanna Visser Adjoian, co-founder and co-director of the Youth Sentencing & Reentry Project, which successfully fought to end Philadelphia’s policy of billing parents for the costs of detaining their children.

A report released in 2016 by Juvenile Law Center, a Philadelphia nonprofit, found that in almost every state and the District of Columbia, minors who appear in the million-plus cases heard in juvenile court each year may be charged for multiple court-related costs, fines and fees. Courts use the money for witness fees, court operations, public defender fees and probation supervision. They also spend it on health care, GPS monitoring and drug tests, among many other items and services.

The fines and fees vary widely. In Alameda County, California, which did away with its fees in 2016, juveniles in the justice system were charged an average of $2,000 to pay public defenders and cover the cost of GPS monitoring, among other services. For a single parent earning the federal minimum wage, that translates into about two months of salary. In Idaho, juveniles are fined $1,000 each time they violate probation.

Racism and Recidivism

In many places, the fees are similar to what adults are charged. The difference is that few young offenders have the money to pay them — many, in fact, are too young to work. That means their parents or guardians often end up being liable for their fees and fines. For youth and their families, failing to make the payments may result in incarceration, suspension of driver’s licenses and an inability to expunge or seal records.

Research suggests the fees and fines have a disproportionate impact on families of color and may fuel recidivism. They also can cost cities and counties more to collect than the revenue they bring in. In a report it released last year, the Policy Advocacy Clinic at the University of California Berkeley Law School cited a case in which Los Angeles County spent $13,000 trying to collect $1,000 from a grandmother who was charged for her granddaughter’s detention.

A 2017 report by the National Center for State Courts found that most states do not have systems in place to evaluate a family’s ability to pay fees for juvenile probation supervision or to waive those fees when appropriate to do so.

Several years ago, the strife in Ferguson, Missouri, helped raise awareness of the role court fees play in keeping the poor caught up in the criminal justice system. Conservatives such as Right on Crime, a Texas-based legal policy group, have joined liberals in opposing excessive fees and fines as costly — since they lead to more people being incarcerated — and unfair.

Nevertheless, many courts are reluctant to relinquish the revenue, according to Jay Blitzman, a juvenile court judge in Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Courts do rely on the fees and fines as a revenue source, Blitzman said. But ultimately he believes they are counterproductive.

“Current practices not only run the risk of criminalizing poverty, but dramatically exacerbating racial disparities,” he said. “There’s a better way to do business.”

Advocates fighting the fees also note that it can be politically difficult to convince lawmakers and the public to waive fees for people who have been charged with crimes.

Republican state Rep. Lowry Snow, who sponsored the Utah legislation, said some of his colleagues worried that eliminating fees would let youthful offenders off the hook. So the law limits fines for minors under age 16 to $180. The limit for minors over 16 is $270.

“We’re trying to find a balance,” Snow said. “Holding them accountable but not making it so onerous that they become locked into the system for long periods of time.”

Looming Action?

Last month, the Alabama Juvenile Justice Task Force reported that more than three-quarters of juvenile probation officers believe young offenders should be required to pay all of their fees and fines before being released from probation. But the Alabama report also recommended minimizing fees and suggested that juvenile probation shouldn’t be extended for technical violations such as failing to pay fines and fees.

A recent report by a similar panel in Tennessee found “the imposition of fines and fees can significantly increase the likelihood of youth reoffending” and recommended their elimination. (The Alabama and Tennessee reports were supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts, which funds Stateline.)

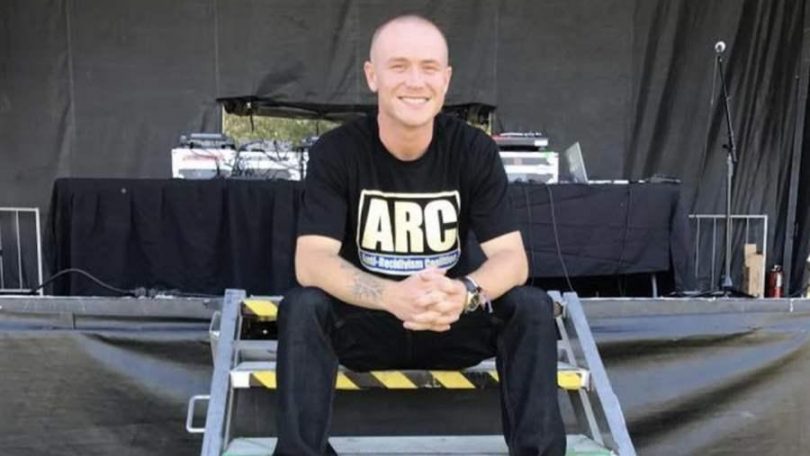

Meanwhile, in California, 21-year-old Michael Rizo is hoping the new law there will help people like him avoid significant fines and fees.

Rizo was arrested for the first time when he was only 11. His mother had her hands full trying to raise him in their rough-around-the-edges neighborhood, where a local gang ruled.

Rizo says he was repeatedly arrested, on charges of burglary, robbery and violating the terms of his probation. And as his arrests piled up, so too did his juvenile court fees: Ankle monitoring bracelets cost $30 a night; twice-weekly drug tests cost $20 a pop; and juvenile detention cost as much as $30 a night, he said. His mother ended up having to declare bankruptcy, Rizo said.

At 18, when he was released from juvenile detention, the first mail he received was a bill for $10,000, to cover the costs of his incarceration.

Theresa Wiltz is a staff writer for Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Image: Michael Rizo