Global Tel*Link guarantees to pay Los Angeles County $15 million in cash each year for allowing the corrections telecommunications giant to provide the phone system for LA County jail inmates.

It pays a somewhat lower kickback, known euphemistically as a “commission,” to Orange County, for its jail phone contract

And how can GTL afford that kind of high dollar “commission?” .

It’s not a problem in that, while prison phones are relatively expensive to maintain, the prices charged for jail inmates to call home are so usuriously high—more than 10 times that of a non-jail-originated call—that there is still plenty of profit to go around for the service provider after it has paid off its county clients, according to a class action lawsuit announced last Thursday by attorneys Ron Kaye, Barry Litt, Scott Rapkin, and Michael Rapkin in behalf of families of inmates in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

“Tens of thousands of California jail inmates… most of whom are not convicted of anything but are facing charges, have been held hostage to grossly unfair and excessive phone charges, forcing them to pay these charges in order to maintain contact with their loved incarcerated ones,” wrote the attorneys in a statement announcing the lawsuit. “These charges force family members desperately trying to maintain contact with their inmate husbands, parents and children to pay for totally unrelated jail expenses or give up their primary lifeline of communication.”

WHEN PAY PHONES ARE MONEY MACHINES

So how much in the way of profit are companies like Global Tel*Link actually making off their various jail and prison contracts, after expenses?

Good question.

Global Tel*Link (GTL) is the nation’s largest jail and prison phone provider with 50 percent of the business. However, GTL and Securus—the number two in the industry with 20 percent of the lock-up call business (including for Riverside and San Bernardino counties)—are both owned by larger privately held companies, which means their annual reports are not publicly available.

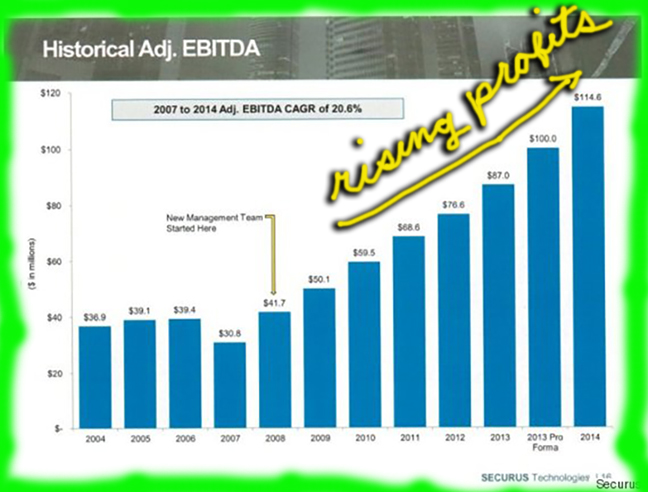

Luckily, however, earlier in the year the Huffington Post managed to get their hands on some leaked images from Securus’ 2014 report sent to investors, which showed that the company made $114.6 million in profit in 2014, and is expected to make more this year, if the cheery leaked image you see above is any guide.

Also, both telecommunications companies have been bought within the past five years, with acquisition prices that are also telling: Global Tel*Link was sold for $1 billion in 2011 to American Securities, a New York-based firm. Securus was sold in 2013 to ABRY Partners, based in Boston, for $640 million.

In other words, we can safely assume that those who provide phone service in jails and prisons are doing so with a healthy financial return.

FAMILIES TAKE THE HIT

As the legal complaint points out, the inmates themselves don’t pay for the high-priced calls. It is their families who are charged “unjust, unreasonable and exorbitant rates” to communicate with sons, daughters, husbands, wives, mothers, fathers and friends.

It doesn’t help matters, the attorneys note, that inmates of the county jails in question are generally “relatively poor and lack significant financial resources…” This is true for the simple fact the majority of those residing in county jails—as mentioned above—are awaiting trial. And those who are not poor, who are awaiting trial, generally manage to bail out and go home while they wait—unless they are accused of a violent crime, thus they represent a threat to public safety.

Among the lawsuit’s plaintiffs is Star Salazar, a mother of two, who is enrolled in community college and has plans of becoming a medical radiologist. Since her husband entered LA County’s Men’s Central Jail, she juggles paying the family’s bills with the cost of letting her kids talk to their locked-up father. Her kids love and miss their dad, she says, “and my husband needs our support during this very difficult time. Why are we, a family simply trying to do the right thing, punished for keeping in touch with our loved one?”

Another plaintiff is Hilda Alarid, whose mentally ill son, Aaron Araiza, is in San Bernardino’s West Valley Detention Center. Alarid is close to her son, and worries that his problems will worsen without daily phone calls from her, which she simply can’t afford. “My son suffers every day from his psychological condition,” she says. “I am the person he turns to for comfort and support.”

It should be noted, by the way, that study after study on jail and prison recidivism shows that, among the main predictors that allow former inmates to succeed after release from lock-up is their ability to retain strong relationships with their families and communities. To put it another way, it is in the best interest of public safety for inmates to be able to have an affordable way to stay in regular contact their loved ones at home.

IF CALIFORNIA’S PRISONS CAN DO IT, THE STATE’S JAILS CAN DO IT

In 2001, I wrote a story for the LA Weekly that was critical of the ridiculously high priced inmate call system in California’s prisons and jails. But in 2007, the state of California began to phase out phone-generated commissions at its state prisons, ultimately eliminating the commission system by 2010. Prior to August 2007, calls from California’s prisons were $1.50 + $.15/minute for local calls, $2.00 + $.22/minute intrastate. Now, with no commissions, current per minute rates for intrastate and local calls are $0.13 and $0.09, respectively. Thus, a 15-minute intrastate call without the kick-back system is 61.70% less than when the State received commissions. It’s still more than one would pay when not in prison. But it is reasonable, and the state’s expenses are adequately covered.

So, if the state can manage to do without the money it used to rake from the overpriced phone call fees paid by poor families with incarcerated loved ones, shouldn’t the counties be able to manage too?

The lawsuit’s attorneys say yes. Moreover, if they prevail against the four counties named in the complaint, a legal precedent will be set, and they believe the rest of the state’s counties won’t have a choice.

Ms. Fremon’s article has hit upon a key fallacy in public choice theory. The theory of public choice argues (correctly) that government failure is ubiquitous, that special/narrow interests (e.g., unions, community groups, lobbying associations, racial groups, farmers, et cetera) capture and corrupt the public good, and distort the common-good aims of administrative units of government. The fallacy lies in public choice’s alternative solution – for example, non-public, private, market-based jail, law enforcement, and alternative dispute resolution services – which is no panacea and fraught with problems. In this case, Los Angeles County receives a reported $15 million annually from private company Globel Tel so that Globel Tel (effectively a coercive monopoly) can manage and maintain the pay phone services of the County’s jail pay-phone systems. This activity is permitted by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, signed by Mr. Clinton, which de-regulated telephone service providers, among other things. Globel Tel makes this agreement with the County for rent-seeking purposes (e.g., charging telephone call commissions that increase profit over time). To recoup the $15 million payment per year to the County (and any concomitant campaign contributions siphoned to decision-makers or their friends), they operate the pay phones at a profit. Here, the theory of public choice essentially argues that markets and market-based companies offer efficiency advantages over public/government administrative units, thus increasing the sum of justice (e.g., reliable access to communications with people in local communities). The American military contractor system has adopted this public choice perspective in terms of national defense contracting, as has much of public education in developing human capital in the schools and universities. It has created a public-private convergence across many institutions where up to forty percent or more of those services are provided by private firms (contractors). There is a particularly effective counter argument to the public choice theorists regarding market failure when trying to provide complex goods and services, having to do with the very nature of efficiency, which I will not raise here.

So, where does it leave this particular example? Given the lifeline nature of those particular pay telephones for especially vulnerable people, given the laws and regulations ensuring the incarcerated with periodic access to telephones, given that the incarcerated have no real, functioning market from which to choose a provider for best service at least cost (they’re virtually ‘hostage’ to a single market robber baron as implied by the facts of the article, not so unusual given the circumstances but worth noting), it would seem reasonable that each county should bid these contracts as a non-profit service and forgo receiving the budget-subsidizing $15 million, which is basically a rent-seeking use-tax imposed upon the backs of incarcerated prisoners (their families or loved ones, etc.) in its own jails. (Yes, the County is as much to blame for leveraging its own financial avarice, as Globel Tel is to blame for engaging in rent-seeking behavior on the backs of the poor. Both are operating as economic parasites.) In my view (assuming these facts are accurate), this government-market, LA County-Globel Tel collusion to swindle the families and loved ones of the poor bastards in the jails is the real scandal here. Each telephone company operating in this market sector should be encouraged, as a corporate citizen and public benefit company, to consider the service a moral and business imperative. Providing and maintaining those telephones at cost, perhaps with small local tax incentives or offsets, would seem a fitting compatibility between public and private sectors. LA County and Globel Tel ought to consider the ‘but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I (or my loved one)’ moral argument (or Rawls’ ‘veil of ignorance’ argument).

Finally, someone or some people in County government likely got a political benefit out of negotiating this contract. Who was it? Globel Tel may have made financial contributions to political campaigns. To whom? Let’s examine elected officials’ last ten years of campaign contributions. Did any County employee subsequently go to work for Globel Tel between 2007 and this year? Anyone from the LASD? Did anyone from County government get paid consulting fees from Globel Tel? This smells like a dirty bit of business. Fine investigative journalism, Ms. Fremon. Bravo, but don’t stop: those Globel Tel contracts need to be thoroughly examined, and pdf’d. The lawsuit may have them, as discovery exhibits, and yet I fear this class action may settle with a nondisclosure agreement of some kind. FOIA next?

No doubt that Global Tel, tag teaming with the County of Los Angeles personifies “Big Pimping”.

Hopefully the Board of Supervisors can do “due diligence” and correct this multi-million “Con Game” of convenience.

Mr. Koestler, the corporate terrorists have struck again.