Los Angeles Unified School District, is increasing allocated money for high-needs middle and high schoolers, but is failing to properly distribute funds for high-needs elementary students, according to a report from United Way of Greater Los Angeles.

In the past, California’s education budget allocation was severely inequitable. More money was often given to affluent school districts, short-changing the schools (and the students) that needed the state’s financial support the most.

In 2013, to address the problem, California enacted the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), a weighted funding approach that allows districts, rather than the state, to decide how a portion of their funding is spent. The formula aims to level the playing field for high-needs students who are severely underserved by school districts.

The LCFF sets aside extra money for high-needs kids—specifically kids from low-income households who qualify for a free or reduced-price school lunch, kids who are learning English as a second language, homeless students, and foster children. These kids make up nearly 60% of the total LAUSD population. The formula requires districts to set up goals and action plans for helping vulnerable students transcend achievement gaps and barriers with regard to attendance, suspensions and expulsions, and interactions with school police.

“The challenge is quite simple: move new resources to schools that serve the most disadvantaged students, and identify what program strategies truly work inside schools,” the report reads.

The state set aside $3.8 billion in LCFF funds for schools between 2013 and 2015. Yearly, this equates to about one-fifth of the total state budget for schools, according to the report.

Among the 31 high schools with the largest concentrations of underserved students, funding increased by nearly 50%—$9,596 per student—over pre-recession spending.

This is not the case in the state’s elementary schools, however.

According to the report, the LCFF money each elementary school gets “bears little relation” to the number of high-needs pupils enrolled.

Elementary schools with a student body comprised of fewer than 60% high-needs students experienced a 20% funding increase between 2013 and 2015, while schools with 90% high-needs kids experienced only a 14% increase in LCFF funding.

The report criticizes LAUSD’s failure to put together a comprehensive strategy for closing the “opportunity gap” in Los Angeles. In addition, “best practices that are empirically identified are not reflected as budget priorities.”

And four years into using the budget system, the district has not implemented an assessment of the more than 40 initiatives it has put in place, and what impact they have on narrowing gaps in achievement and opportunity, the report says.

These aren’t the only problems the district is having with getting LCFF implementation right.

Last year, the ACLU and Public Advocates filed a legal complaint against LAUSD for counting close to $450 million in separate special education funding as money to “increase or improve” services for the LCFF’s targeted high-needs students. (WLA reported on the issue: here.)

The report calls on Los Angeles to “distribute additional resources to schools that serve high concentrations of high-need pupils – the very students who generate over $1.1 billion in additional aid from Sacramento.”

California “has managed a return to pre-recession levels of school spending, but per-pupil support still lags behind most other states,” the report says. “We look forward to fighting alongside LAUSD leaders for increased education funding that is strategically invested in effective means for lifting historically underserved communities and schools.”

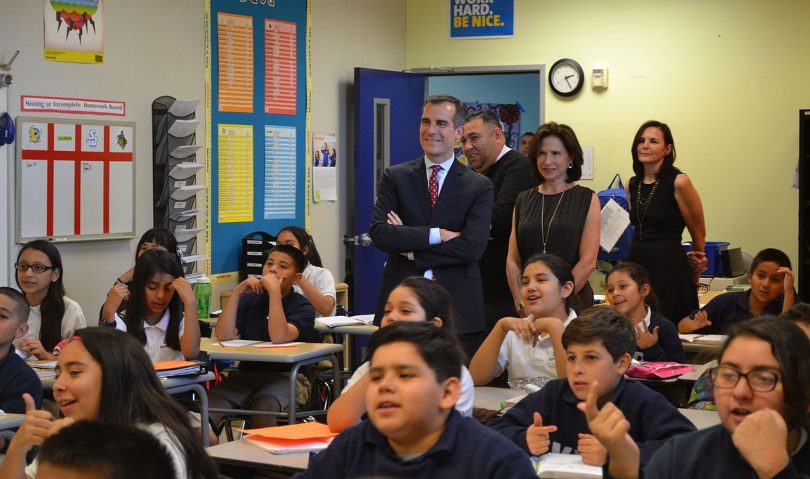

In the photo above, LA Mayor Eric Garcetti visits students at KIPP Boyle Heights.