With the 2016 passage of Proposition 57, which took the power to send kids to adult criminal court out of the hands of prosecutors and gave the control back to judges, courts should be sending few kids to adult court. But a new report from the W. Haywood Burns Institute, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, and the National Center for Youth Law says that the last decade of data on prosecuting kids as adults—and the racial disparities therein—point to the need to “remain vigilant” to ensure that the same disparities are not repeated under the new law.

Specifically, the voter-approved law eliminates the ability for prosecutors to “direct file” youth as young as 14 into adult court, and requires that every youth have a transfer hearing in front of a juvenile court judge. During a hearing, the judge considers the particulars of the case, including the kid’s background and other circumstances, and adheres to a set of criteria to decide whether the youth is “fit” for the juvenile system.

In addition to racial disparities, direct file and judicial transfer data from 2006 to 2016 reveal significant variance between how often CA counties use direct file and transfer hearings to send kids to adult court.

From 2010 to 2016, nine counties—Alpine, Calaveras, Del Norte, Glenn, Inyo, Lassen, Mariposa, Plumas, and Sierra—reported that no kids were sent to adult criminal court. At the same time, kids in Kings, Madera, San Joaquin, Sutter, and Yuba counties were prosecuted as adults at rates more than three times the state average.

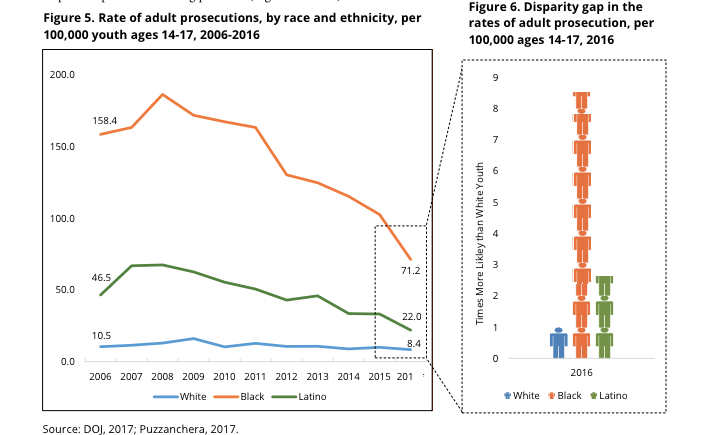

During those five years, for every white youth sent to adult court, 3.9 Latino kids and 12.3 black kids were sent to adult court.

Just last year, black youth were 8.5 times more likely than white youth to be tried as adults. Latino kids were almost three times as likely.

While kids of color were prosecuted as adults at higher rates than their white peers in nearly every county between 2010 and 2016, the size of the racial disparities varied greatly across counties. For example, while Alameda County had a rate of adult court prosecution that was lower than the state average, black youth were 65 times more likely to be direct filed or transferred to adult court than white youth.

At the state level, between 2006 and 2016, 53 percent of white teens who had a judicial transfer hearing by a judge were kept in juvenile court compared with 27 percent of black teens and 25 percent of Latino teens.

Even with the repeal of direct file, these racial disparities are likely to continue, according to the report.

Between 2006 and 2015, juvenile felony arrests declined in California by 66 percent, but transfer and direct file cases did not “keep pace,” according to the report. The number of kids sent to adult court dropped only 38 percent.

Immediately after the passage of Prop. 57 in November 2016, prosecutors were blocked from direct filing cases against juveniles.

The report suggests that the late-in-the-year change may have contributed to a 31 percent reduction in direct file cases over 2015’s numbers.

However, “the extent to which counties are now pursuing a transfer hearing in cases that would have been direct filed will not be known until annual data for 2017 are released in mid-2018,” according to the report.

The report’s authors make several recommendations to protect kids from racial disparities in adult court transfers post Prop. 57.

First, all stakeholders, including judges, prosecutors, public defenders, and probation officers should receive training on transfer hearing procedures, including “a comprehensive review of the developmental factors that must be considered when making a transfer decision.” This training is especially urgent for counties that used to send kids to adult court most often.

In addition, probation departments are responsible for assessing kids and making recommendations to the courts regarding whether youth should be prosecuted as adults. According to the report these assessments “should be informed by a comprehensive social history report conducted by a trained social worker who considers the totality of the circumstances in a youth’s case and examines all relevant developmental factors, including their maturity, history with trauma, and family and peer influences.

Counties must also collect and analyze more data on prosecuting kids as adults, including “the number of motions for transfer filed, the number that were withdrawn with a stipulated plea agreement, the number of probation officer recommendations for transfer, and the court’s rate of concurrence with those recommendations,” according to the report.

Families and communities must also be included in all stages of the transfer process. Family members “should be regarded as valuable partners with insight into the lives of these youth and the most appropriate treatments and placements for them,” the report states. “Similarly, community-based organizations must be permitted to actively engage in the transfer process by working with families to advocate on behalf of youth…”