On October 11, 2017, Governor Jerry Brown signed into law SB 395, a bill requiring that youth 15-years-old or younger cannot be questioned in what is known as a custodial interrogation, without first consulting a lawyer—either in person, by telephone, or by video conference. The bill prohibits a kid from waving Miranda rights without such a consultation. Furthermore, the young person may not waive that consultation with the lawyer either.

The law makes an exception when a police officer “who questioned the youth reasonably believed the information he or she sought was necessary to protect life or property from an imminent threat.”

SB 395 went into effect on January 1, 2018.

In order to make the legal demands of the new law work in Los Angeles County, the LA Public Defenders Office has made juvenile attorneys available “24/7,” to meet the potential new need for counsel. Furthermore, the PD’s lawyers’ numbers are distributed to police stations. The county’s Alternate Public Defender’s office is similarly on board with.

“We’re getting a lot of calls already, at least one or more a day,” said Assistant Public Defender Winston Peters.

On the prosecution side of things in LA, on December 1, 2017, a month before SB 395 was to kick in, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office distributed what it called a “One Minute Brief” on the subject of the new law as it pertains to the questioning of kids.

The two-page document, which WitnessLA has obtained, was distributed to local law enforcement ostensibly to help them deal with the new statute. (You can find the document here.)

District Attorney’s Office spokesperson Shiara Davila-Morales quickly explained the brief’s purpose to us via email.

“The One-Minute brief,” she wrote, “simply serves as an informational tool to ensure that the law, as established by these binding precedents, is properly applied,”

Indeed the brief explains the general meaning of the law, but also explains at length that, “since the statue applies only to ‘custodial interrogation,’ it is not implicated by interrogation that is non custodial, nor by custodial questioning that is not interrogation.

“Absent actual custody or custodial restraints (school isolation, drawn weapons, cuffs, cages), neither Miranda nor [SB 395] applies,” states the instructional brief.

“Interrogation delayed until after the removal of custodial restraints…. is not ‘custodial’ either.

The “bottom line,” the brief states at its end, is that the new law “reinforces the wisdom of interrogating criminal suspects—especially those 15-and-under—before custody occurs or after it ends.”

(Emphasis theirs, not ours.)

While the LA D.A.’s office said that the brief—which was written by Devallis Rutledge, a veteran prosecutor and former Santa Ana PD officer, who now serves as Special Counsel to District Attorney Jackie Lacey’s office—is a routine teaching tool, defense attorneys and other legal professionals we spoke with were less willing to dismiss its affect as routine.

“Here’s the thing,” said civil rights attorney Ron Kaye when asked about the D.A.’s brief. “Police officers are trained to in any way possible to obtain an incriminating statement. That’s their goal. And district attorneys fight tooth and nail to demonstrate that the statements provided by a suspect were voluntary, and that the suspect was not in custody, and didn’t trigger any kind of prophylactic measure that would have prevented the admission of an incriminating statement.”

As long as everyone stays inside the boundaries of the law, that’s fine.

But, regarding SB 395, the premise is supposed to different, Kaye said.

“Here the premise is that, scientifically speaking, juveniles are far more prone to provide false confessions” than adults, “and they are much more prone to being manipulated to provide statements that are incriminating that don’t necessarily reflect the truth.”

It was with this premise that the bill was passed by the California legislature, he said.

“So its manipulative and abusive to tell law enforcement how they should try to extract an incriminating statement from this population” without appropriate protections.

“It’s essentially taking the entire premise of the legislation and ignoring it. And that causes me concern,” said Kaye.

Attorney Elizabeth Calvin, senior advocate for the Children’s Rights Division of Human Rights Watch, also expressed concerns with the brief.

“On the one hand you want the D.A.s to be considering what the law is, and analyzing it,” said Calvin, who was also involved in writing SB 395. “But it’s hard not to feel that this is… wink, wink….’here’s how to get around the law.’

“I expect the D.A.s to first and foremost seek to uphold the law—especially constitutional law,” Calvin said. “And this is not only about the constitutional rights of people, it’s about the constitutional rights of really vulnerable people. The origin of this law was the recognition that people under 16 do not really have the same ability to understand their rights that older people do.”

Growing brains and Miranda confusion

As Kaye and Calvin suggest, in the most general sense, SB 395 was proposed and passed as one more step in a multi-decade movement to get the nation’s criminal justice system to recognize that kids are cognitively and emotionally different than adults, a difference that virtually every other kind of law has long recognized.

In California, for example, kids cannot sign binding contracts, make or revoke a will, buy or sell property, smoke, drink alcohol, go to certain movies, vote in state or national elections, join the army without parental permission, or consent to have sex with an adult, without serious legal consequences for that adult.

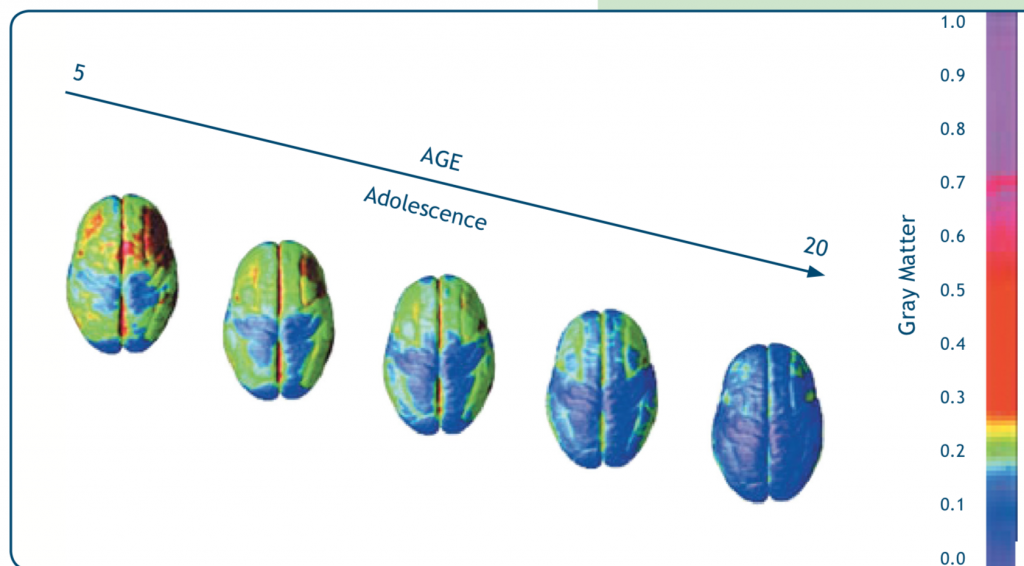

When Magnetic Resonant Imaging (MRI) came into widespread use in the 1990s, the idea that there was a fundamental difference between teenagers and adults received a massive new corroboration. Prior to the advent of MRIs, neuroscientists thought that the human brain quit developing in early childhood. Through the new imaging, however, researchers discovered that certain important areas of the brain, particularly those in charge of decision-making, continued to develop well into adolescence, and that certain kinds of brain development went on into one’s early to mid 20s.

Maturation of the Adolescent Brain (MRI Images)

Society for Neuroscience, 2011, via Annie E. Casey Foundation

Yet a series harsh sentencing laws affecting kids that were passed in the state from the middle 1980s through the early 2000s were at odds with those discoveries.

In the last few years, however, California has passed a series of new laws that are more reflective of the now overwhelming body of research showing that teenagers’ brains are different from those of adults.

As WitnessLA reported last year, SB 395’s co-authors, California State Senators Ricardo Lara (D-Bell Gardens) and Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles) cited the scientific research as their prime reason for proposing SB 395.

Lara and Mitchell—along with others who helped with the writing of SB 395—were also alarmed by cases like that of a 10-year-old with developmental disabilities named Joseph who in 2011 shot his abusive neo-Nazi father, Jeffrey Hall, in the head while he slept. The night before, Jeffrey Hall had threatened to burn their Riverside home down while his family was sleeping.

When a police detective asked Joseph if he understood his Miranda Rights, the boy answered, “Yes, that means I have the right to remain calm.”

And then there was the matter of false confessions.

Kids confessing to crimes

The mission of the National Registry of Exonerations, a collaborative project between University of California, Irvine, where the registry is now located, the University of Michigan School of Law, and Michigan State University School of Law, is to “provide comprehensive information on exonerations of innocent criminal defendants in order to prevent future false convictions by learning from past errors.”

With this goal in mind, the Registry has collected, analyzed, and disseminated the details of all known exonerations in the United States, from 1989 to the present.

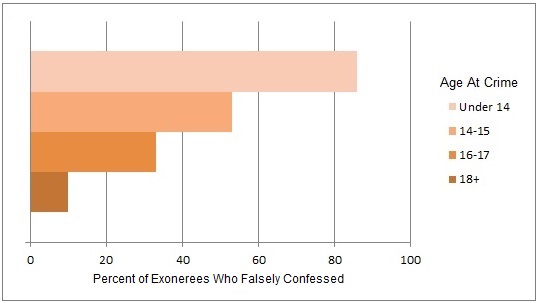

In exploring the 2167 exonerations the Registry has counted as of this writing, one of the oddest elements of these innocence cases is the fact that, approximately 12 percent of those whose convictions were overturned, confessed to crimes that they did not commit.

When it comes to exonerations of those who were convicted as kids, the number jumps to 42 percent.

Moreover, the younger the kid, the greater the chance for a false confession.

Of the kids exonerated who were 14 or 15 when they were first arrested, 58 percent of those kids,falsely confessed.

With kids 14 or under who were exonerated since 1989, 86 percent of them falsely confessed.

The matter of case law

Several of the attorneys we spoke with about the brief, either on or off the record, told us they were surprised that although the D.A.’s brief cites a lot of case law in explaining its various points, it leaves out what is arguably the most important piece of recent case law on the matter, namely a 2011 U.S. Supreme Court decision known as J.D.B. v. North Carolina. Thus in leaving out the principle enshrined in this particular ruling, the brief may be giving law enforcement faulty advice, legally speaking.

The ruling for J.D.B., written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, concerns a case in which police stopped and questioned a 13-year-old boy (identified as J. D. B.) when they spotted shim near the site of two home break-ins. Five days later, a digital camera matching one of the stolen items was found at the seventh grader’s school and also seen in his possession. A police investigator went to the school, and a uniformed police officer working at the middle school took J. D. B. from his classroom to a closed-door conference room, where police and school administrators questioned him for at least 30 minutes. Before beginning to ask questions, officers did not give him Miranda warnings or the opportunity to call his grandmother, who was his legal guardian. Nor did the officials tell the boy he was free to leave the room.

J.D.B. first denied any involvement with the home break-ins. But then, after officers told him he would face juvenile detention if he did not tell the truth, he confessed.

The primary issue in the case was whether or not J.D.B. thought he was in custody when he was being questioned, and whether or not his age needed to be considered when determining whether or not the 13-year-old was in “custody,” and thus needed to be Mirandized. The Court determined that his age did need to be considered, and overturned the various lower courts’ rulings.

“It is beyond dispute,” wrote Sotomeyor, “that children will often feel bound to submit to police questioning when an adult in the same circumstances would feel free to leave. Seeing no reason for police officers or courts to blind themselves to that commonsense reality, we hold that a child’s age properly informs the Miranda custody analysis.”

“J.D.B. is the other part of Miranda,” said Calvin. This includes the question, “’Do you feel free to go?’”

Every beat cop should know, she said, that legally, “ ‘custody’ is when you feel you aren’t free to go. But this memo makes it sound like it’s just when you’re handcuffed or you’re locked up…”

Ian Kysel, a Staff Attorney with the ACLU of Southern California, agreed.

“The D.A.’s ‘bottom line’ doesn’t read as very rights-friendly when it recommends as ‘wisdom’ that law enforcement should try to interrogate children under 15 in circumstances in which important constitutional rights may not formally attach,” he said.

“In the context of children, given that there’s such a robust jurisprudence recognizing that children are different in material ways than adults, including because they are especially susceptible to the influence of authority figures, this is very troubling.”

“It’s vitally important that all aspects of the system, including both the investigatory function and the adversarial function, reflect the core insight of now more than a decade of Supreme Court jurisprudence that criminal law and procedure apply in a particular way to children and youth,” added Kysel, whose past legal work has frequently focused on the rights of kids.

“One would hope that, in their interactions in the field and in the courtroom, the police and the prosecutors would be ensuring that those constitutional rights that apply in special ways to children are being respected.”

Obviously, added Calvin, as a prosecutor “you don’t want false confessions. For that reason alone,” she said, “I’d like to see our district attorney stepping up and saying, ‘yes we’d like to implement this new law as it was intended.’ Instead of saying, ‘If you take the handcuffs off and say ‘you’re not under arrest, then you don’t have to read them their Miranda rights or get them a lawyer.’”

If the legislature wanted to have a lawyer provided before any questioning–as all you quoted wish it to be—they would have written the law that way. They didn’t. Instead, they made it apply only to custodial interrogations and the DA’s office has accurately explained that fact to law enforcement.

Celeste doesn’t want bad kids getting locked up, wants them to all be given therapy because they just don’t understand what they’re doing. Same with lots of adults as well.

Seems like a lot of liberal hand wringing just to insure misbehaving youth have a better chance of beating the case. Is this really best for the kid? Wouldn’t an intervention be more helpful? Regarding the example given in the story, wasn’t everyone better served when the 13 year old confessed to the crime, especially the 13 year old himself? Would it have been better if he would have gotten away with the crime presumably to continue committing more crime, and of course more victims?

The story also leaves out the fact the law already makes allowances for juvenile lack of mental development, (e.g. an entire separate legal and custodial system). Of course Witness La conveniently forgot to mention that.

Or maybe Brown could’ve advocated for having resources readily available for juveniles as soon as they’re arrested.

Nope, that money was better spent on legal representation for illegal aliens and a train to shuttle them as far from the border as taxpayer money will allow.

A gap in the law is that it doesn’t require officers to tell the young person whether she/he is or isn’t in custody (orally and provided to the young person in writing). A young person, and many or even most adults, is unlikely to ask the officer. And then a problem of officer said/civilian said may arise too.

An option apparently not included in the law, would have been simply to make all youth statements given to law enforcement without the presence of attorney inadmissible. That would skip all this confusion.

That is the liberals mentality let all the criminals of the world alone, but the police. Where is the outrage when under the false pretense of justice and reform, James McBuclkes encourages his investigators to obscure the truth against deputies, to fabricate statements, exaggerate facts or destruction of evidence, to coach lying witnesses to frame a deputy into a crime? We hear and know of many cases like that in the sheriff’s department, yet, no liberal is concerned about that, disgraceful…

There are countless examples of cases where the suspect does not confess or is not questioned by police, yet there is still sufficient evidence to convict. Do you really want officers to question suspects, possibly illegally, and get a conviction that may be overturned later? That just sounds ridiculous. Considering the number of convictions that are gained without a confession, the previous comments seem to be making this new law a bigger deal than it really is. What’s wrong with doing something to reduce false confessions? Do you actually want innocent people in jail? Just follow the law for Pete’s sake instead of trying to get around it! All of you and the LA DA need to have a little confidence in the abilities of deputy DAs and the investigative skills of officers.

I actually find these type of briefs informative and helpful. There are literally thousands of laws on the books, some ambiguous and some clear. This type of brief gives all the relevant information and what can and can’t be done when contacting juveniles. It’s not a loophole, not an escape clause and doesn’t encourage bad behavior or policing, rather it provides all the facts on what’s legal and proper. Your FEELING on the law is irrelevant to what the law actually says and allows.