A new report from UC Berkeley Law’s Policy Advocacy Clinic reveals wide variations in how counties have responded to SB 190, a law eliminating the collection of administrative fees from families for kids’ juvenile justice system-involvement.

Juvenile justice system fees push low-income families into serious financial strain and debt, while pushing their kids further into the justice system.

These fees have, in recent years, been high as $33 per day for lockup, and $24 a day for electronic monitoring. Families across the state have also faced fees associated with drug testing, diversion, program services, legal counsel, and more. LA’s own Youth Justice Coalition and Berkeley Law students at the East Bay Community Law Center first drew attention to the issue, and pushed for reform at the local and state levels.

The law, which went into effect on January 1, 2018, does not ban counties from continuing to collect fees and fines assessed before 2018. Counties have to choose to stop pursuing those old unpaid fees. Some counties have wiped away millions of dollars in old debts. Other counties have been less eager to give up the potential revenue.

In the handful of years preceding the passage of SB 190, the Berkeley Policy Advocacy Clinic was instrumental in stopping the fees in several California counties, including Contra Costa, where the county wasn’t even making enough money from the fees — totally approximately $2,000 per case — to cover the cost of collecting them.

Both Contra Costa and Alameda County stopped collecting juvenile justice-related fees in 2016, and Sacramento County in 2017, in response to the clinic’s research showing that the collection of administrative fees from families had no rehabilitative, restorative, or retributive value. (Los Angeles and San Francisco do not charge these administration fees to kids’ families. LA County approved a moratorium on the fees in 2009, while SF never charged in the first place.)

Hoping to determine counties’ compliance with SB 190, the Berkeley law students sent scores of Public Records Act requests all over the state.

Their efforts revealed that many counties have gone even farther toward justice debt reform than the legislation requires.

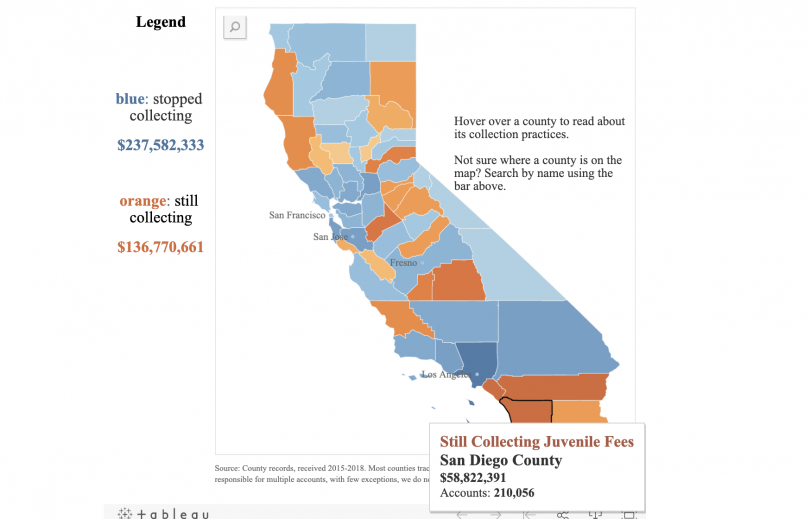

While SB 190 didn’t force counties to wash away old debts from juvie justice fees, 36 counties chose to wipe the debts or at least stop collecting them.

The collective move unburdened families of over $237 million in debt.

Los Angeles, one of the debt-erasing counties, forgave just under $90 million in 2018.

“The majority of counties have taken it upon themselves to end the collection of more than $237 million in previously assessed fees,” said Stephanie Campos-Bui, the Policy Advocacy Clinic’s supervising attorney and co-author of the report. “Such widespread relief is unprecedented in the history of criminal justice reform, and can serve as a model for debt-free justice in other states.”

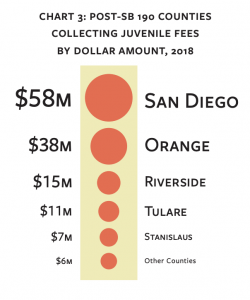

Yet 22 counties are still collecting more than $136 million in fines, according to the report. Approximately 58 of those millions are weighing down San Diego families. San Diego, along with Orange, Riverside, Tulare, and Stanislaus counties, represent more than 95 percent of the $136 million in old debt still being pursued. (The clinic produced a handy interactive map that shows how each county has responded to the law.)

The law clinic found that some counties are also actively violating the new law’s ban on charging youths between the ages of 18-21 in the adult system for their home detention, electronic monitoring, and drug testing.

A handful of counties are also hitting families with fees by sending child support orders to parents with kids in out-of-home placements, according to the report.

The law students also found that many counties had not yet notified families that they had been relieved of their debts, an issue the report urges counties to address.

“… The bill will only be as effective as the implementation on the ground,” clinic director and report co-author Jeff Selbin said. “We’re committed to making sure counties comply with the new law, and we’re urging them to go beyond what’s required to make the most of this opportunity to get money out of the juvenile system once and for all.”

It is concerning that children need to rely on their families to pay these fees when for a variety of reasons that may not be possible. There are many very good, caring families who deeply love and care about their children but may absolutely lack the financial ability to pay.

There are also families from all across the socioeconomic spectrum who may be dysfunctional and not a source of advocacy or support for their children. Children may be in families that are physically or sexually abusive, neglectful or otherwise just terribly dysfunctional. Children need support for their own issues. When it is possible to involve the family in providing that support, this is ideal. But children should not be penalized for either their family’s socioeconomic status or issues.

Dr. Garbarino described an illustrative example of a dysfunctional family in his book “Listening to Killers.” He and a psychiatrist are conducting an interview of the brother and sister of a defendant and request that they recall their childhood.

He writes that “The interview came to a head when the brother was asked about his relations with his extended family. “I hate them all,” he said. “In fact,” he continued, “I have a hit list.” “A hit list?” Dr. Smith replied. “What do you mean by a hit list?” The brother calmly explained, “The hit list is the order in which I plan to kill them. I revise it every month. If they are good to me that month they get moved down on the list. If they treat me bad, they get moved up.” […] “I remember thinking of the brother, ‘This is the guy who isn’t in jail!'” (Garbarino 147)

Some families are like this. There are parents who may be far more dysfunctional than whatever issues their children are dealing with. Asking people who are not themselves healthy and functional to contribute in a meaningful way to their children’s progress is not fair to the children. Children should receive support and rehabilitation for their own issues, with family involvement to whatever extent is realistic. But assuming that every family who has a child involved in the justice even wants to be helpful is an unreasonable expectation. These fees are also incredibly unfair to the many deeply caring families who simply cannot afford them.