by TheDeath Penalty Information Center,

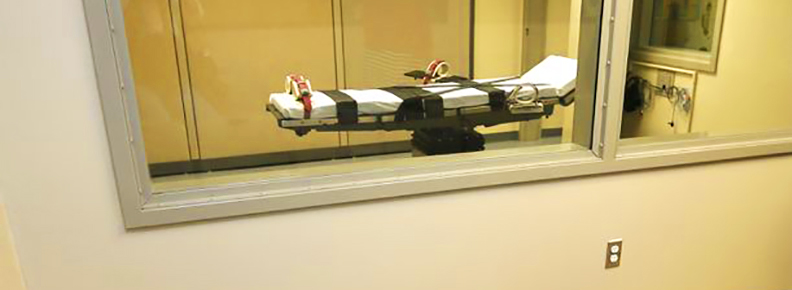

Oklahoma’s legacy of botched executions has continued to grow, as media witnesses to the October 28, 2021 execution of John Grant reported that Grant suffered repeated convulsions and vomited over a nearly 15-minute period after he was administered the controversial execution drug midazolam.

Grant’s execution was Oklahoma’s 113th since executions resumed in the United States in 1977 — tied with Virginia for the second most of any state during that period. It was also the state’s first execution since botching the executions of Clayton Lockett in April 2014 and Charles Warner in January 2015 and then aborting the execution of Richard Glossip in September 2015.

Media witness Sean Murphy of the Associated Press reported in the post-execution news conference that Grant began convulsing almost immediately after the midazolam was injected into his body. After being administered “[t]he first drug — the midazolam — he exhaled deeply, he began convulsing about two dozen times — full-body convulsions,” Murphy said. “Then he began to vomit, which covered his face, then began to run down his neck and the side of his face.”

After prison personnel wiped the sick off Grant’s face and neck, he began to convulse again and again vomited, Murphy said.

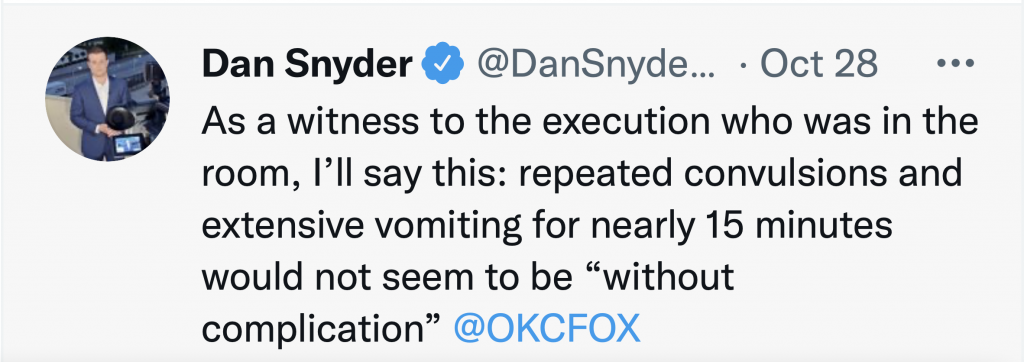

Oklahoma City Fox television anchor Dan Snyder corroborated Murphy’s account.

“Almost immediately after the drug was administered, Grant began convulsing, so much so that his entire upper back repeatedly lifted off the gurney,” Snyder reported. “As the convulsions continued, Grant then began to vomit. Multiple times over the course of the next few minutes medical staff entered the death chamber to wipe away and remove vomit from the still-breathing Grant,” Snyder wrote in his minute-by-minute account of the execution.

About 15 minutes into the execution, the media witnesses said, prison personnel declared Grant unconscious and the second and third drugs in Oklahoma’s execution protocol — the paralytic drug vecuronium bromide and potassium chloride, which induces heart failure — were administered. He was pronounced dead six minutes later at 4:21 p.m. Central time.

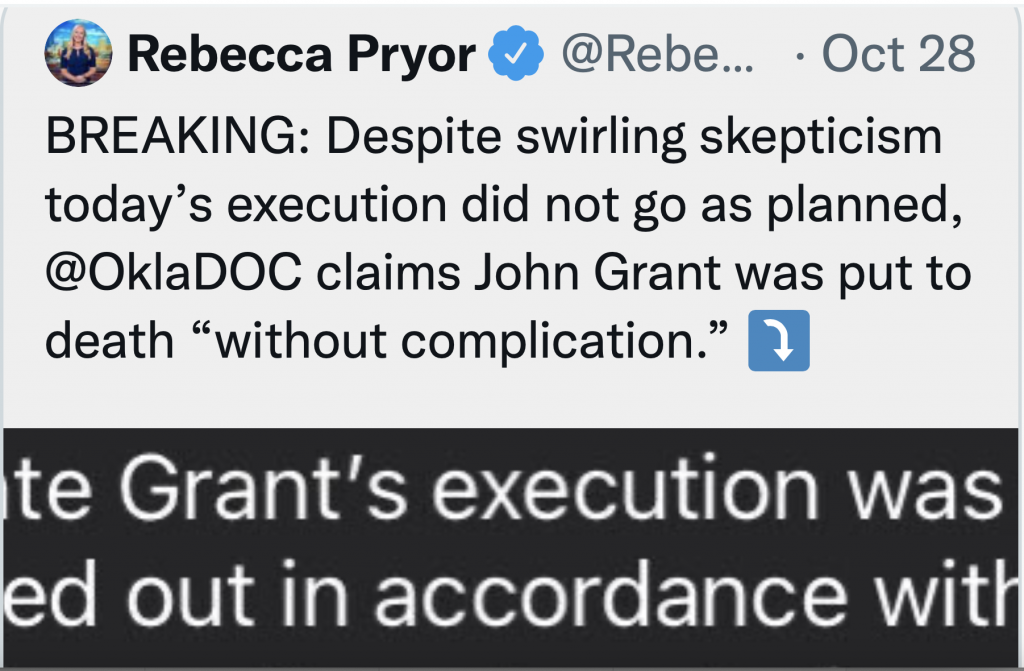

Prison officials initially ignored the evidence of an execution gone wrong, issuing a statement from communications director Justin Wolf that “Inmate Grant’s execution was carried out in accordance with Oklahoma Department of Corrections’ protocols and without complication.”

In a news conference one day after the execution, ODOC Director Scott Crow called the eyewitness accounts of the execution “embellished,” describing the convulsions reported by multiple witnesses as “dry heaves” and Grant’s vomiting as “regurgitation.”

Snyder responded bluntly to ODOC’s sanitized description of the execution. “As a witness to the execution who was in the room, I’ll say this: repeated convulsions and extensive vomiting for nearly 15 minutes would not seem to be ‘without complication,’” he tweeted.

Advocates and law reformers called on Oklahoma to halt the six remaining scheduled executions. Assistant federal defender Dale Baich, who is one of the lawyers representing the state’s death-row prisoners in their constitutional challenge to Oklahoma’s execution protocol, said that, “[b]ased on the reporting of the eyewitnesses to the execution, for the third time in a row, Oklahoma’s execution protocol did not work as it was designed to.”

“This is why the Tenth Circuit stayed John Grant’s execution and this is why the U.S. Supreme Court should not have lifted the stay. There should be no more executions in Oklahoma until we go [to] trial in February to address the state’s problematic lethal injection protocol,” Baich said.

Oklahoma City University law professor Maria Kolar, who served on the bipartisan Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission that recommended reforms to the state’s death penalty, told NBC News that the state’s rush to carry out executions before the February 2022 trial on the constitutionality of its execution method was reminiscent of the mindset that led to Lockett’s botched execution.

“This time reminds me of the last time,” Kolar said. “[T]he attitude of, ‘You can’t stop us, we’re going ahead. Even if they’re not made to wait, the state should wait and respect the process.”

Oklahoma had not attempted to carry out an execution since September 30, 2015, when then-Governor Mary Fallin at the last minute called off Richard Glossip’s execution after being informed that ODOC had received the wrong drug, potassium acetate, instead of the potassium chloride required as the third drug in the state’s lethal-injection protocol.

It was later revealed that the state had known for months that it had obtained and used the same unauthorized drug to execute Charles Warner in January 2015. Media witnesses reported that Warner had said during his execution, “It feels like acid,” and “My body is on fire.”

Oklahoma also botched the execution of Clayton Lockett in April 2014, failing for 51 minutes to set an intravenous execution line and then misplacing the line in Lockett’s groin, injecting the drugs into the surrounding subcutaneous tissue. With Lockett writhing on the gurney in a pool of blood, the execution was called off but 43 minutes after the drugs were first administered, he died.

“We keep having problems with executions here,” Abraham Bonowitz, the Director of Death Penalty Action, said after Grant’s execution. “The whole idea that Oklahoma can’t seem to get it right, you know, should be a wake up call.”

In a press statement issued two days before Grant’s execution, ODOC said that it was prepared to resume executions “[a]fter investing significant hours into reviewing policies and practices to ensure that executions are handled humanely, efficiently, and in accordance with state statute and court rulings.” ODOC said that it “continues to use the approved three drug protocol which has proven humane and effective. … Extensive validations and redundancies have been implemented since the last execution in order to ensure that the process works as intended.”

After Grant’s execution, Death Penalty Information Center Executive Director Robert Dunham issued a statement that “to say this is another botched Oklahoma execution would be inadequate. Oklahoma knew full well that this was well within the realm of possible outcomes in a midazolam execution. It didn’t care … and the Supreme Court apparently didn’t either.”

In his October 29 news conference, prison director Crow said that Oklahoma did not intend to change its execution protocol or procedures as a result of Grant’s execution.

Editor’s post script

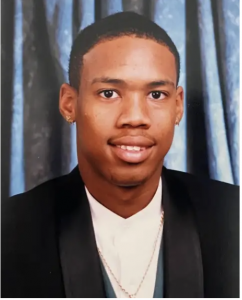

Julius Jones is another man residing on Oklahoma’s death row who is scheduled for execution by the same three chemicals that his attorneys believe subjected John Grant to excruciating pain and physical distress.

Jones is to be put to death on November 18, for a murder he has always insisted he did not commit.

On Monday, November 1, however, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board voted 3 to 1 to recommend that Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt grant clemency for Jones.

Instead of death, the parole board recommends that the governor commute Jones’ sentence to life in prison with the possibility of parole.

If neither the court nor the governor successfully intercedes, Jones will be executed slightly over two weeks from now for the 1999 murder of a man named Paul Howell, of Edmond, Oklahoma, who was shot to death in front of his two daughters and sister.

(It should be noted that, Howell’s family members continue to believe that Jones is in fact guilty.)

Jones and his attorneys argue that he was convicted due to “fundamental breakdowns in the system tasked with deciding” his guilt. Among the break downs the attorneys cite are “ineffective and inexperienced public defenders,,” racial bias by the jury, a case fraught with “junk science,” and alleged “prosecutorial misconduct.”

This story (except for the Editor’s Post Script above) originally appeared at The Death Penalty Information Center.

The Death Penalty Information Center — or DPIC — in case you’re unfamiliar, is a national non-profit that, more than any other source, serves both the media and the public with in-depth analysis and information on issues concerning capital punishment.

Founded in 1990, the DPIC conducts briefings for journalists, and generally serves as a resource to anyone in need of information on the issue. The DPIC also produces critically important reports on various collateral topics related to the death penalty, including the arbitrariness of the death penalty, its high cost, the racial disproportionality with which it is applied, and the innocence factor.