Editor’s Note:

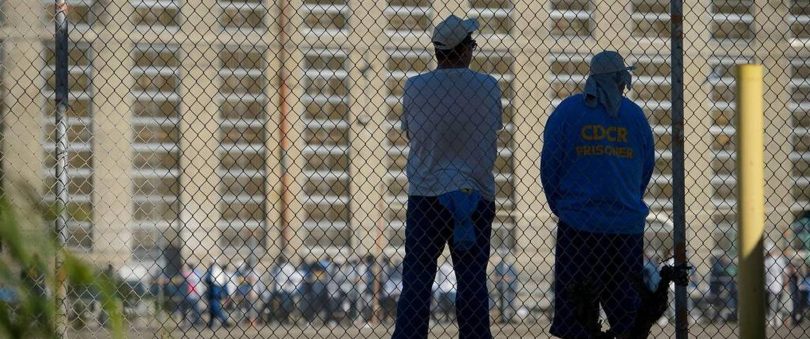

As many readers are aware, WitnessLA has been publishing a series of essays written through the FirstWatch project at San Quentin State Prison. The two authors of the essays, Adnan Khan and James King, are also San Quentin inmates who aim with their writing to, as they put it, explore “the connections, challenges, and intimacies between self, society, and incarceration.”

In the essay below, Adnan Kahn probes the effect of “objectifying” language in prison, and the possible changes a different use of language might bring.

Happy reading.

Sticks and Stones

By Adnan Khan #F-55145

On his way back to his housing unit one day, my FirstWatch teammate Eric “Maserati E” told me he was pulled over and searched for a random pat-down. A Correctional Officer (C.O.) told Eric to put his hands on the wall as the officer took items from Eric’s pockets. The other officers stood close by and watched. Once the random stop and frisk was over, the C.O. handed back the few items Eric had in his pockets (identification card, pens, guitar pick, and a couple of FirstWatch and Re:store Justice stickers). The CO. asked Eric what the stickers were about and once Eric informed him, Eric offered the C.O. the stickers and said “here you go man, support the project!” Unfortunately, the C.O. was not receptive. He not only rejected the stickers, but told Eric “I don’t support anything you inmates do.”

“Actually, I’m NOT an inmate,” Eric responded.

“What are you then?” the C.O. asked, which seemed to Eric as more of a challenge than a genuine question.

“I’m a human being.”

Eric’s reply ignited the C.O.’s response.

“You’re not a F-ing human being, you’re a F-ing inmate to me, and you’ll always be a F-ing inmate.”

Eric collected his belongings. “Well I consider myself a human being,” he said, “and I’m sorry you feel that way.”

The C.O. responded by saying, “I’m sorry you feel that way.”

Eric looked at him and the other C.O.’s who were standing there. “Alright, well, God Bless y’all,” he said, as he proceeded to go into his housing unit. The other C.O.’s who stood by had mixed responses. One looked on, one nodded, and one replied “God bless you too.”

I’ve found accounts like Eric’s to be common occurrences in prison. The verbal abuse can also come from paid prison staff or volunteers. These examples are not limited to people working in prisons, but are extensions linked to the biases of society at large. I believe there is a toxic culture of acceptable language that is the driving force behind the objectification of people who are incarcerated. What people largely associate with terms such as “inmate”, “convict” or “felon”, is a dangerous monster capable of random harm. That is what generally comes to people’s minds.

The interpretations of these terms that describe humans who are incarcerated are deeply rooted into the public’s consciousness. These words have meanings that are usually loaded with prejudices, judgements and fear. Because of that, “inmate” can mean a person who does wrong, not a person who is bettering themselves. “Convict” can mean a monster who has harmed, rather than a person who is making amends. “Felon” can mean a dangerous man, rather than a loving father or a funny brother.

When turning people into objects or degrading a human being to someone who is less-than, can make it easier to hurt or continue harmful behavior towards them. Objectifying language can be heard all over our culture. Women are called the “B-word.” It is easier to treat a “b” with disrespect than it may be to treat a “woman” with disrespect. Objectifying language is used in the military and police force when they say “shoot the target.” It is much easier to shoot the “target” than it is to shoot the “husband”, shoot the “father” or to shoot the “brother.” Objectifying language is used to perpetuate racism with the “N-word” and homophobia with the “F-word.” It is also used in gang culture with derogatory terms for opposing gang members. And similarly, objectifying language is seen and heard in our justice system when referring to a person as an “inmate” “convict” or “felon” rather than a “human being.”

I believe a new popular vocabulary should replace the current language around prison and people in prison. I believe this can encourage critical thinking and reshape the roles between human beings, incarcerated and otherwise.

New vernacular can allow us to reflect and reconsider the humanity of people in prison; the funny brothers, loving fathers and caring daughters who get smothered when they are placed beneath these offensive labels. This could help us, human beings who are incarcerated, toward a healthy recovery, safer learning environments, and an eager return to a much more welcoming society.

I believe using humanizing language is one of several starting points in approaching a new justice system that works towards healing rather than punishing. It’s much easier to heal a human, just as it is much easier to punish an “inmate”.

Author Adnan Khan is the Co-Founder of Re:store Justice and FirstWatch, a media project created and produced entirely by a group of journalists incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison. Khan shares his worldview through storytelling, with the hopes of using his platform to mentor youth and provide success opportunities for neglected children.

Additionally, Khan works in collaboration with survivors of crime, incarcerated men, district attorneys, CDCR officials and other stakeholders to move towards healing and integrating communities. He is currently serving a 25-to-life sentence and has been incarcerated over for 15 years.

Re:vision, where this essay was first published, is a series of personal blogs written through the FirstWatch project at San Quentin State Prison. Through traditional postal mail letters, the journalists delve into a list of topics, looking at them through a lens that includes the complex interweave of relationships between self, society, and incarceration, also opening themselves up to responding to perceptions and questions posed by the public.

FirstWatch is a media project started by a group of men incarcerated at San Quentin, in collaboration with Re:store Justice, which works in partnership with incarcerated people, survivors of crime, district attorneys, and the community. Their mission is to re-imagine and reform our criminal justice system to be one of true inclusion and justice.

Thank you for this well written & thoughtful piece. I just retired for the Courts system after 34 years as a trial court Judge. For the past 5 years I have endeavored to utilize a trauma Informed approach. If your approach is used as well as educating front line folks on the triggering impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences; if we remembered Sentencing is about Punishment AND Rehabilitation AND Restitution perhaps individuals would leave prison better than when they arrived, healed & with skills to maintain a lawful & productive life. Mass incarceration is expensive & does little to improve recidivism. Our Society can do better.

Thank you for this well written & thoughtful piece. I just retired for the Courts system after 34 years as a trial court Judge. For the past 5 years I have endeavored to utilize a trauma Informed approach. If your approach is used as well as educating front line folks on the triggering impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences; if we remembered Sentencing is about Punishment AND Rehabilitation AND Restitution perhaps individuals would leave prison better than when they arrived, healed & with skills to maintain a lawful & productive life. Mass incarceration is expensive & does little to improve recidivism. Our Society can do better.

25 years in prison is not even close to enough time to compensate for taking the life of our dear Kevin. It’s been 17 years and I think about him every single day. Go back to prison you murderer!!!!