by Adnan Khan

I just found out my friend died. He contracted COVID-19 in San Quentin State Prison after a botched transfer of positive cases from the California Institution for Men. As I write this in my grief, I cannot imagine the devastation his family is experiencing with the loss.

I knew him well. I was incarcerated with him in San Quentin where I was serving a life sentence. We spent a lot of time together on the yard, in self-help groups and educational classes.

I also know San Quentin, the prison, really well. I spent my last four years there, completing a total of sixteen.

His death was preventable and his safety should’ve been prioritized. All it would’ve taken was political courage to reduce the prison population significantly. Tragically, given what he was left with — trapped in a tight box with COVID-19 — survival was out of his control and death became inescapable for him.

Most people won’t care about my friend’s passing. His incarceration gave the state legitimacy to deny him his humanity. As a society, we accept punishment and torture as the only exchange for breaking a law, not redemption. Inhumane treatment becomes acceptable–so as we enter incarceration, the human being gets extracted from the body. Our dignity is confiscated along with the personal, material belongings during the initial strip search.

All of this is made possible by society’s narrow focus solely on the crime. Subsequently, the narrative is shaped as a permanent boogeyman-esque identity for that person. We hardly ever factor in the next decade or two of that human being’s journey to make that assessment whole and accurate.

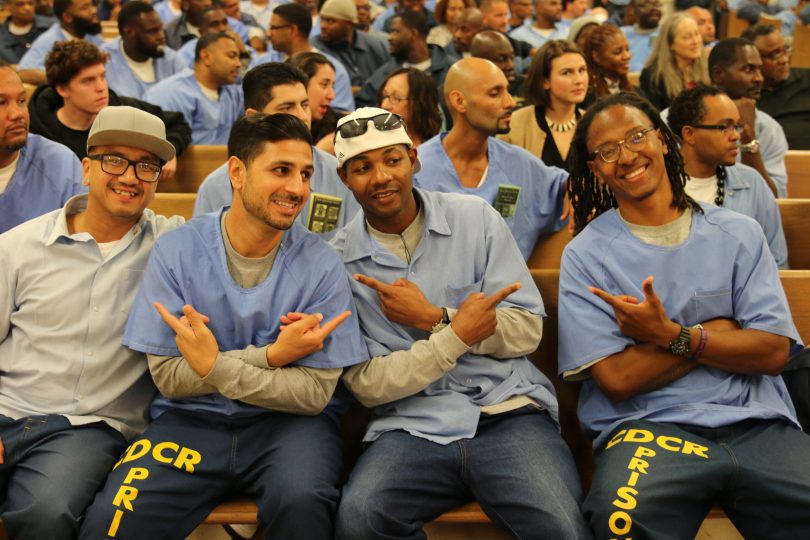

What the public lacks is something we as incarcerated people have an abundance of in prison. Proximity. In prison, we get to know each other extremely well. As the years crawl and the hours get slower, we fill each challenging second by dissecting each other’s lives. We become each other’s test studies and learn the anatomy of the proverbial heart. We spend hours upon hours crammed in tight spaces calculating the psychology behind each other’s thoughts.

Trust and safety are destinations in prison. If found, a sudden ability to go into the depths of each other’s innermost shame, pain, trauma, remorse and the thorough details of a person’s accountability for the harm they’ve caused are unlocked. Often for the incarcerated, this level of intimacy can bring a more profound understanding than with one’s own family.

We carry each other’s stories with us wherever we go.

The heart-wrenching, often gruesome experiences shared with us do not get left behind upon our release either. It’s not that I remember, it’s that I know. I know who was molested by their father, who was beaten with closed fists by their foster parent at 8 years old, and whose friend was shot and died in his arms at the age of 14. For the larger society, these stories don’t match the face tattoos or visible scars. These stories don’t match the warm smiles or laugh lines we see on the prison yard daily. It’s at times like a deception of the senses where I’m staring at the body and face of a grown adult, yet hearing the sounds of a child’s shriek.

Furthermore, I know why they committed their crimes. This is not to make an excuse for the crime but to understand why. Why they committed robbery, assault, or murder.

Those in the rest of society are deprived of such a narrative. They’re deprived of the level of accountability and the depths of remorse my fellow incarcerated people have expressed for their victims. I wish those who have never visited prison could see how many good people exist inside. I wish they could observe how much of our lives are spent trying to make amends, somehow, some way. Instead, their identity is forever trapped in a time capsule that society and politics has forced them into.

As an activist who has been impacted by incarceration, I don’t have a work life that is separate from a personal life. Detaching the two feels immoral to me. I can’t clock out of caring about someone. Getting to know people comes with a burden. Especially in prison. Especially when leaving those you care about behind upon your release. Proximity comes with a set of responsibilities of which you become the project manager. Survivor’s guilt places deadlines on you that you have to reach. When it comes to the case of my friend, “deadline” turned out to be a horrifically accurate term.

I feel safe around the people you might fear the most.

Our organization’s slogan is “from proximity to policy.” It is my proximity that gives me access to empathy. Most members of society and political leaders are tragically uninformed about people in prison, yet, make deadly decisions based on their fears.

Our obligation should be to know people in their totality, and only then can we create safe policies which address the needs of everyone. Instead, the public’s ignorance has incarcerated our loved ones’ identities and has handcuffed their humanity to their crimes.

Everyone should have the privilege, like I did, to get to know a person as a whole. Society saw my friend as someone who was not deserving of dignity. They believe the person who did the crime deserved to die of COVID-19. But if they truly knew who my friend was, he would’ve been released to his family. Rather, they saw him as an enemy of the state. They chose not to acknowledge his humanity.

People we incarcerate are not our enemies. They are victims of societal failures and their crime does not negate their restoration. They are brothers and sisters, daughters and sons, and they are someone’s really good friend. My really good friend. As much as we can argue about who the enemy is, one thing that is inarguable is that humanity’s enemy is neglect.

Adnan Khan is the Co-Founder and Executive Director of Re:Store Justice, Adnan works in collaboration with survivors of crime, currently and formerly incarcerated people, district attorneys, CDCR officials and other stakeholders to move towards restorative practices.

While incarcerated he Co-Founded the organization Re:Store Justice and worked on the felony murder rule legislation, Senate Bill 1437. The bill passed in August 2018 and on January, 18th 2019, Adnan was the first person re-sentenced under the new law he helped create.

In addition, during his incarceration, he created FIRSTWATCH, a media filmmaking project produced entirely by incarcerated men at San Quentin State Prison that still produces short films today. His sentence was also commuted by Governor Jerry Brown in December 2018. He is an Art for Justice Fellow and is on the California Reentry Enrichment Grant steering committee.

This essay was created as part of the FirstWatch project at San Quentin State Prison, an initiative that Adnan Khan created.

People out in society, good people like Herman Cain, are also getting Covid-19 and dying. Thugs, drug peddlers, and killers in prison are far less likely to get sick with it, and you libs need to quit worry so much about them. I’d love to understand why you are so preoccupied with criminals. No, that’s a lie – couldn’t care less, just disgusted with it.

The death rate in prisons and jails is minuscule in comparison to the deaths in nursing homes. Yesterday I read an article about the largest nursing home in California, no deaths. Fed and State surged resources to this nursing home. Why! Because the mayor of San Francisco’ relative lived there and asked for help. This state needs to steps up and take care of all of its elderly, not just those related to powerful Democrats. Your friend likely had better care and consideration than most of those house in skilled nursing facilities. Those who feel any sympathy, please do the math. Compare deaths in nursing homes to those incarcerated before you get sucked into this foolishness. As for many of those incarcerated being previous victims, to a degree, this maybe true but not all victims become victimizers. Breaking the cycle of violence does require separating the most violent from society.

“As I write this in my grief, I cannot imagine the devastation his family is experiencing with the loss.”

Heart wrenching….but…WHAT was your friend sentenced to LIFE for, Khan? Can you imagine the devastation the family of your friend’s victim(s) are experiencing?

And again, not a WORD about YOUR victim in your amazing biography. Here’s the facts of your case, people can decide for themselves if you or Kevin Leonard McNutt is the actual victim. Your statements to the investigator are telling:

https://www.leagle.com/decision/incaco20090325010

Thank you for continuing to advocate for those behind walls, and for continuing to do the right thing after finding your second chance.

You’re the same person who would want a cop fired for even the slightest hint of excessive force, while advocating for a convicted murderer to be given his “second chance” out in society.

Hey Adnan, here’s a glimpse of who has been released.

Among those released was Terebea Williams, 44, who served 19 years of an 84 years-to-life sentence for first-degree murder, carjacking and kidnapping. She was freed last week after being deemed at high medical risk for the virus. Williams’ victim, Kevin “John” Ruska, picked her up to drive her to work in 1998 but the pair argued and Williams forced him into the trunk of his own car at gunpoint. She shot him when he tried to escape, then brought the wounded man more than 700 miles (1,126) kilometers) from Tacoma, Washington, to a motel in Davis, California. There she gagged him and tied him to a chair. He died from the infected wound.

Save your sad stories Adnan. Law abiding citizens have a greater expectation of safety than the monsters you keep.