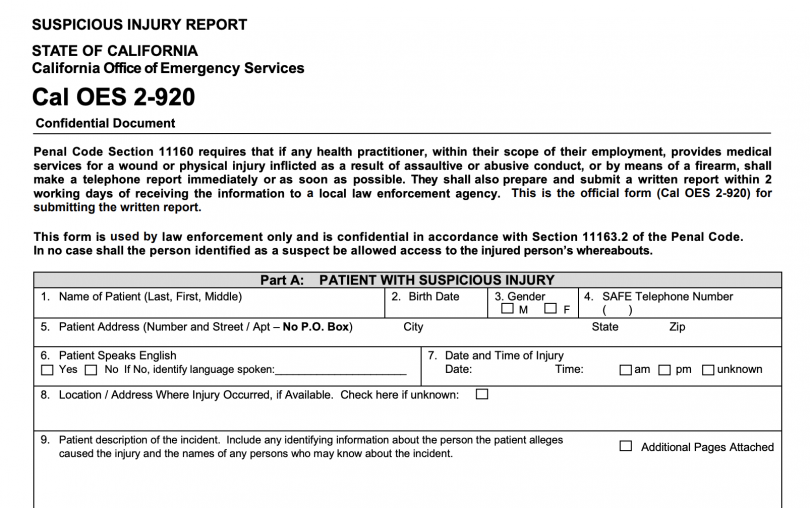

Under current California law, a healthcare provider who suspects a patient’s physical injuries were caused by assault or abuse is required to make a report to law enforcement.

While intended to protect victims, this mandated reporting law can deter people experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) from seeking medical care or other assistance.

A bill currently before the Senate Public Safety Committee seeks to address this issue, by giving victims a choice about whether doctors make a report — as long as the injuries suffered are not life-threatening.

Under AB 3127, doctors and other health professionals suspecting an adult patient’s injuries resulted from assault or abuse would only be required to report the case to law enforcement if an injury was life-threatening without immediate medical care, or if the abuse was against a child or elder.

In an instance involving less severe physical harm to an adult, a doctor would be required to briefly counsel the individual and offer referrals to domestic violence advocacy groups. Doctors would still be able to make a law enforcement report at the injured person’s request.

“Studies show that survivors of abuse want health practitioners to provide survivor-centered, trauma-informed, and nonjudgmental care,” the bill states. “Requirements to report all adult violent injuries can result in reduced survivor help seeking, increased danger in some situations, and a reluctance of health practitioners to address abuse.”

Yet, the option is still available for individuals who want doctors to contact law enforcement because it would be dangerous for them to make the report themselves.

“While medical mandated reporting to law enforcement for firearm wounds or other very serious injuries is common in many states, California is one of only three states that still have such broad and harmful requirements to report explicitly for domestic and sexual violence-related injuries without patient consent,” according to Futures Without Violence, one of the bill’s co-sponsors. “Although this law was a well-intentioned attempt to ensure health care providers take violence and abuse seriously, no research has shown that medical mandatory reporting to law enforcement has positive safety or health outcomes for survivors.”

A handful of other bills introduced this year seek to address other aspects of how California handles domestic violence. Some bills failed to pass out of fiscal and public safety committees and off the house floors before a May 24, 2024 deadline for the Senate to pass bills introduced in the Senate, and for the Assembly to pass bills introduced in the Assembly.

One of those stalled bills, AB 2354, by Assemblymember Mia Bonta (D-Alameda), would have made more victims of domestic violence, human trafficking, and sexual violence eligible to have their own related convictions vacated.

Under current law, a person arrested or convicted of a non-violent offense can petition the court for vacatur relief if they were a victim of human trafficking, domestic violence, or sexual violence at the time the crime was committed, if the crime was directly related to their victimization, and if a judge believes that vacating the arrest and/or conviction is in the best interest of justice.

Under the 2024 bill, which was held in the Committee on Appropriations before it could make it to the Assembly floor, a person convicted of any abuse or trafficking-related crime would be eligible to petition the courts. Additionally, the new crime would only have to be related, rather than directly related, to be eligible. The bill would have also removed the requirement that a court find granting relief to be in the best interest of justice.

Another bill, aimed at protecting victims from their abusers, SB 1394, would shield people fleeing domestic violence from having their phone-connected cars tracked by the person who caused them harm. The bill would require car manufacturers to terminate remote vehicle access if a person presents a dissolution decree, temporary order, or domestic violence restraining order that grants them “possession or exclusive use of the vehicle.”

“We have known for some time that GPS-tracking technology in cars is being exploited by domestic violence abusers, but unfortunately, some car manufacturers are refusing to act to address this potentially fatal problem,” wrote Senator Dave Min (D-Irvine). “Survivors of abuse should not have to fear technology as a tool for further victimization by abusers who can track and harass them. SB 1394 creates a process for survivors of domestic abuse to rapidly terminate remote access to a vehicle and ensure their safety and privacy.”

SB 1394 passed out of the Senate and is now in the Assembly.

Funding for victim services may also get a much-needed boost via legislative action this year.

In 2021, the Little Hoover Commission, a state oversight board, detailed the ways California could better address intimate partner violence in a 48-page report called “Beyond the Crisis: A Long-Term Approach to Reduce, Prevent and Recover from Intimate Partner Violence.”

In the course of its review of California’s strategies for addressing IPV, the Little Hoover Commission found that the funding sources meant to help victims recover were unsustainable over the long term.

The federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) distributes money to community-based organizations working with survivors in need, and to states for direct financial assistance for victims. Because the funding relies on fines and fees levied against people convicted of crimes, and is not supported by tax dollars, states are getting far less money deposited into their victim compensation funds.

Victim services in California will receive $87 million for fiscal year 2024 — a reduction of approximately 43% from the $153.8 million allocated the previous year, according to the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence.

One bill seeks to bridge the funding gap by establishing the California Crime Victims Fund in the State Treasury, and by adding a new sentence enhancement to the penal code.

AB 2432 would establish a “corporate white collar criminal enhancement” through which a court can impose an additional fine on a corporation convicted of a misdemeanor or felony. That money would go into the California Crime Victims Fund. In addition to the fiscal sentence enhancements in these cases, the bill would require courts to impose a separate restitution fine that would be split between the Crime Victims Fund and the prosecuting agency.

The bill passed out of the Assembly and is now in the Senate.

A related bill, AB 1956, which would have required the state’s Office of Emergency Services to put some of its own funding toward crime victims services if federal funding for the state’s Crime Victims Fund is reduced by 10% or more from the previous year.

The bill was held in the Assembly Appropriations Committee and will not advance this year.