The following personal recollection represents only one tiny shard of the day that is forever seared into LA’s collective memory. We welcome your own shards of memory, should you be inclined to share them.

April 29, 1992: Winds of Violence Blow From Two Directions

Twenty-five years ago, on April 29, 1992, Los Angeles exploded. But even before four LAPD officers were acquitted by a Simi Valley jury, triggering a five-day spasm of catastrophic violence in the city, Los Angeles was already living through the deadliest period in its history. Homicides in LA County had reached record heights the year before the riots, with nearly 40 percent of those killings designated as gang-related.

At the time, I was spending most of my working hours reporting on gangs in what were then the combined public housing projects of Pico Gardens and Aliso Village in the Boyle Heights area of East Los Angeles. I was 18 months into researching a book on Father Greg Boyle, who was becoming known as the city’s gang priest, and on the six active street gangs who claimed territory within the mile-square boundaries of Pico-Aliso.

The afternoon that the verdict in the Rodney King beating case was announced, I was on my way to the projects to talk to some homeboys whose lives I’d been tracking for the book, after which time I was going to drive with Father Greg on a series of errands.

Entirely apart from the citywide storm that would break with staggering force before the day was out, it was already a perilous week in Pico-Aliso.

A few days earlier, a member of a smallish Crip set that was one of the six projects gangs, had been shot and killed by a member of one of the other projects gangs, the members of which were primarily Mexican American. The murder itself was already round two of a deadly game of tit-for-tat. It seemed that in the midst of an argument over something or other, the dead boy, who had the unlikely street name of Chicago,* had pulled out a gun and shot a member of another one of the projects gangs in the foot.

Rumor had it that, during the shooting, a friend of the foot-shot homeboy had a gun trained on Chicago from a nearby apartment roof and fired a couple of warning rounds, thus discouraging the Crip from shooting further. It was assumed that the foot-shot gangster, a baby-faced 16-year-old whom I’ll call Romeo, or one of his friends, namely the roof shooter, had tragically upped the ante by killing Chicago.

By this time, I’d been reporting on the projects gangs for long enough that I knew most of the significant players, and their families. In this case, although I had not known Chicago, who was just out of prison, I realized with dread, I did know both of the teenagers who could easily be Chicago’s killers.

Thus it was this other, much closer to hand threat of violence that was most on my mind as I was I was driving the 10 Freeway toward Boyle Heights, listening to KFWB all-news radio when, at 3:16 pm on that Wednesday, April 29, the news commentator announced each one of the Simi Valley verdicts separately: Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty. Not guilty.

I remember finding the content of the announcement momentarily confusing. How can one be found not guilty of something that the whole nation saw one do over and over again on video?

The radio announcer said that there might be unrest, which anybody living or working in South or East LA already knew. However, as I drove toward Dolores Mission church, where Fr. Greg was the pastor, the likelihood of citywide violence seemed a distant concern with the shadow of Pico-Aliso’s own unrest looming with what I believed was a more immediate urgency.

The View From Across the River

By the time I arrived at the church, a group of community mothers were gathering in preparation to march to Parker Center to protest the King verdicts. They asked if I would come with them.

I reluctantly declined, explaining that I’d already promised to accompany the priest to the Dorothy Kirby Center, a therapeutic juvenile facility run by LA County probation in which around 70 kids were housed. Fr. Greg went to Kirby to say mass every first Wednesday of the month.

I’d been to Kirby with Greg multiple times before, but this visit was markedly different. During the mass, the kids were oddly agitated. After the service ended, the priest made a habit of visiting various “cottages” in order to talk to kids individually.

It was just before 7 p.m. when we reached the first cottage, where we found all its occupants gathered in a single, jittery clump around the cottage’s television. Hearing us enter, the kids looked up briefly and seemed glad to see Greg, who was generally a beloved figure.

But their gazes were drawn quickly back to the TV where a news clip of a white man being pulled from the cab of a semi truck and viciously beaten by a bunch of young black men, was being replayed over and over in a violent, balletic series of images that careened across the screen in an eerie visual reverse of the tape of the King beating. Greg attempted conversation at each cottage, but the point of diminishing returns was reached quickly; the kids were too agitated, unable to light anywhere for long, even for him.

After Kirby we drove to a Jesuit retreat house in Azusa where Greg had managed to wangle temporary employment as assistant grounds keepers for two Pico-Aliso homeboys. Their work as groundskeepers had reportedly gone well, but they were both dreadfully homesick so Greg promised to pick up the two and bring them back to L.A. for a short visit.

By the time homeboys and priest were safely stashed in my car for the trip back to the projects it was nearly 9:00 p.m. As we neared Los Angeles, we hit a colossal traffic jam, which was our first inkling that something was very wrong in the city. Squinting ahead, I saw that the sky was bright to the northeast of us and also to the south. There were veils of smoke wafting across the waning crescent moon.

It was then that I turned on the radio and we learned what the rest of Los Angeles already knew.

When I finally dropped Greg and the two homeboys at the church parking lot, Pico-Aliso was quiet and dark, a seeming haven from the storm that was quickening everywhere else.

I would not learn until the next morning that, after I left the church, Greg and the two young men had been trapped inside the sanctuary while cars full of Crips had rolled menacingly up and down Gless Street for hours, the dull shine of gun barrels visible out open car windows.

While they began what would be a frightening night of confinement in the church, I was occupied trying to imagine a safe route home.

Flames and Riot Helmets

To my right was Hollywood, where the palm trees had become fantastic torches lining the freeway with furious light, and causing the shutdown of the 101, which would have been my usual way back to where I lived with my then-six year old son in Topanga Canyon. To my left was South Los Angeles, which I knew by now from radio broadcasts was the epicenter. An hour before, Mayor Tom Bradley had ordered the closing of many of the exit ramps on the Harbor Freeway and maybe some on the 10, so going south seemed dicey. Using the radio news as a guide, I decided to head west across the First Street Bridge, straight through the middle of downtown.

I saw the first sign of trouble at what was then the New Otani Hotel at First and Los Angeles Streets. Nearly all of its ground floor windows were smashed and there was fire damage—although, by the time I passed it, the crowd had moved on and little was actively burning. Hoping for more up-to-date information I veered few blocks farther to what was then the LAPD headquarters at Parker Center.

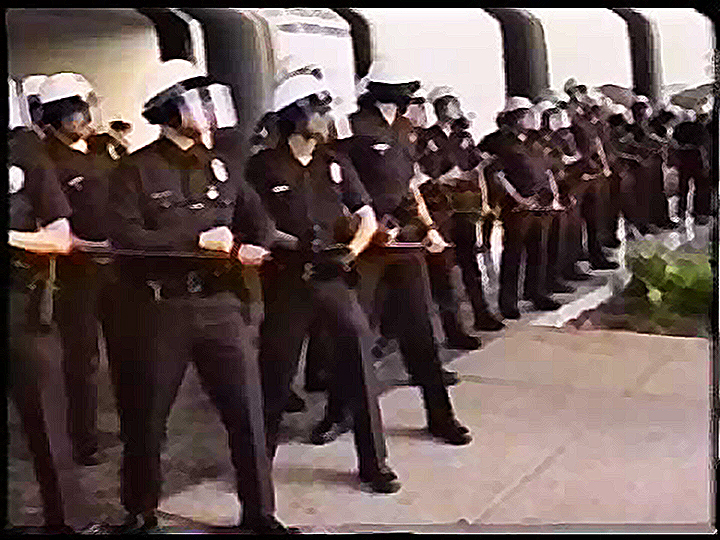

The building was completely surrounded by a shoulder-to-shoulder string of several hundred officers top-heavy with riot helmets. They were protecting the building while the rest of downtown LA was left on its own.

I pulled next to the curb and yelled to the white helmeted officers closest that I was looking for a route west. “Get over to Third Street,” one of the cops yelled. I took his suggestion and raced along Los Angeles Street toward third. But the insurrection was a live thing now, which no one could track or predict. After swerving around first one and then a second set of street barricades, I rounded yet one more corner and ran smack into everything I was trying to avoid.

Up and down the street, people were running, seemingly without a clear direction. They raced and twirled in zigzag patterns across the streets, like whole teams of football running backs turned crazy. The runners were black, brown, many white.

Glass erupted in a musical clatter from every angle, sometimes close sometimes father away. Some of the people had guns in their hands, and I heard gunfire, close by, but sporadic. The bullets were spent, I thought absently, more for effect than for injury. Certain stores were actively burning, while flames barely sequined the facades of others. Every trashcan on the street contained fire, which caused me to think briefly and stupidly of the only visual analogue I had for what I was seeing, the movie Blade Runner.

When I braked to a stop to avoid hitting the runners, a man who was one of those carrying a gun, paused in front my bumper and our respective gazes locked. We only looked at each other for a millisecond, my eyes surely the size of dinner plates, but in that time the gun-toting stranger’s expression cleared and he communicated as distinctly as if he had spoken. This isn’t about you. Keep going.

And so I did.

Grief and Fury

Eventually, I made it through the chaos of downtown, took Olympic Blvd. to La Brea, La Brea south to the 10, then the 10 west to PCH, and north to Topanga, where, after winding my way into the hills, and to my house, I sent the baby sitter home and hugged my son longer than he thought seemly.

For the next forty-eight hours in Los Angeles, it seemed that everything stopped and everything was in motion. However, in Pico-Aliso, and most of the rest of Boyle Heights, there was no rioting, no looting. Although some residents made forays into other areas of the city, most of the projects residents huddled together like a family riding out a hurricane. The gun toting, church-circling Crips of Wednesday night, stayed at home, their grief and fury dwarfed by the larger collective grief and fury.

On Thursday, I stayed close to home too, checking in with Greg a couple of times during the day. He described to me how, on one of his on foot sojourns through the projects, a large and frightened homeboy, whom we both knew, approached him.

“This is the end of the world, isn’t it, G?” said the kid.

Greg attempted reassurance. “Don’t be silly,” he said, “of course it’s not.”

“It took everything in me to muster up the right response to that kid,” Greg told me. “I have never felt so, I don’t know, dark. And it’s not just because the city’s out of control It’s that the city feels like a paradigm for the neighborhood. The neighborhood feels out of control. I feel out of control.”

He paused. “I hope the National Guard arrives soon.”

By Friday, I could no longer bear what felt like the psychological remove of the West Side. I went back to the projects. The dusk ‘till dawn curfew that Mayor Tom Bradley had called was still in place, and the violence would continue in shuddering fits for a few more days. But by Friday night, everyone knew that the fever had broken and spontaneous barbecues bloomed like sudden wildflowers in front yards all over the projects. I made a big salad and joined in one of them given by two families with whom I’d become close. I was grateful to be part of the communal ritual.

The Politicians Arrive

The gang conflict triggered by Chicago’s murder stayed forgotten for almost two weeks while the city reeled in shock. In the first days that followed, politicians made obligatory pilgrimages down to East and South LA, including to Dolores Mission parish.

Greg agreed to allow then presidential candidate Jerry Brown to hold a press conference at Dolores Mission Church, where gang members would speak to the media about the needs of the city’s poorer communities. Young men with colorful street names like Bandit, Puppet, and Champ were remarkably articulate. “Champ,*” who was one of the so-called “big heads” from one of the older projects gangs, talked with eloquence about the need for jobs and opportunities, while the photographers snapped photos of his muscular, resplendently tattooed body draped for optimum photogenic viewing in a white tank top T-shirt.

A young man whom we’ll call William Ayala*, with the street name of Crazy Ace, was the most poetic. “See, if you look you’ll see that Dolores Mission is surrounded by three hills,” he said to the reporters in a velvety cadence. “And no matter where trouble starts, even if it starts up on those hills, it always rolls down to the projects.”

At the end of the press conference, Brown—who had listened with what appeared to be real interest to the young gangsters—announced he would take two homeboys on his next out-of-state campaign swing. A forest of hands flew up to volunteer. Greg selected Champ first, then suggested his best friend, as a second.

But Champ objected. “I think the other person should be from another neighborhood,” he says. “How about Loco?” he said, meaning Crazy Ace. This was a particularly generous gesture coming from Champ, who in those days, prided himself on being the downest of the down.

When Ace and Champ return to Los Angeles a few days later, they were met at the airport by a mass of journalists who peppered them with questions that the newly media-wise homeboys fielded skillfully.

“We did things we couldn’t dream about,” said Champ. “People invited us into their houses and they treated us like kings.”

“We got out of the projects and away from the gangbanging and violence and into the world,” says Rebel. “We were scared but we liked it a lot.”

A reporter asked Crazy Ace if he and Champ would be voting for Jerry Brown in the upcoming presidential primaries. Ace smiled. “We would if we could. But we’re felons. We can’t vote.”

The same reporter asked Champ if he would like to take another such trip. Champ looked the reporter straight in the eye. “We’ll never do anything like this again in our lives,” he said. “We know that.”

Parts of this account were adapted from G-Dog and the Homeboys

*All of the names of the former gang members mentioned in this story have been changed for their privacy.

Life in L.A. prior to three strikes working its magic sounds awful. Are we sure this “reduce the prison population” fad is a good idea? To be honest, it sounds like Celeste rather enjoyed the drama of those days, which kind of explains a lot.

So, many recent “political” rallies and protests have turned violent. The May Day rally/protest in LA promises to be even larger than the Inauguration Day protest. And the media has spent the past week recounting the 92 riots and making ominous comparisons of the economic situation then and now, and how promises of economic revitalization of South LA made after the 92 riots haven’t been kept.

Seems like the media is fanning the flames and encouraging another violent outpouring. But that couldn’t be right, could it?

It’s not fanning the flames, called “keeping the info real”. In most protests, unfortunately the idiots get in the mix and start the stupid shit which includes assaults and vandalism. That includes incidents from every uprising/riot to Laker games & Mayday protesters.

It wasn’t that big and sweet to see a flag burner hooked. Bunch of cowards hiding their faces as usual, this is “the resistance” the right is supposed to be worried about? That Hillary declared herself part of and Hollywood shills? Ha Ha, bring it.

What most people didn’t see was that the national guard along with the LAPD and surrounding police departments sureounded LA and did not let anyone out. Creating a barrier and protecting the surrounding suburbia. I saw the LAPD and firefighters arrive at swap meets and local businesses and actually tear down and break locks and open doors so that looters would loot.