Twenty-five years ago, in 1994, U.S. lawmakers passed a “tough-on-crime” bill that rendered incarcerated prospective college students ineligible for financial assistance that the federal government offered by way of Pell Grants.

Rather than fill the financial assistance gap, many states followed the federal government’s example and reduced incarcerated students’ access to state funding in the decade that followed the passage of the Pell-crushing “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act.”

As a result, college enrollment among people in prison dropped precipitously.

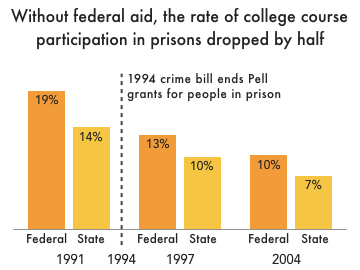

In 1991, approximately 19 percent of federal and 14 percent of state prisoners were participating in college courses, the Prison Policy Initiative points out. By 2004, college enrollment numbers had dropped by half to 10 percent of federal inmates and 7 percent of those in state lockups.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education (DOE) acknowledged the importance of education behind bars, and launched a Second Chance Pell Grant pilot program, that partnered with 65 colleges in just over half of U.S. states, including California. By the 2017 fall semester, the program had 5,000 students enrolled at once.

In May 2019, the DOE announced that the program would expand to include more colleges to reach more students.

The latest figures show that the Second Chance Pell program has awarded approximately 954 credentials to prisoners in the three years that it has been in operation.

But for many criminal justice reform and education advocates, the program does not go far enough to ensure that all eligible prisoners have access to post-secondary education.

This April, U.S. Sens. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) introduced bipartisan legislation — the Restoring Education and Learning Act (REAL) — to address the Pell problem, with companion legislation introduced in the House of Representatives by Reps. Danny Davis (D-IL), Jim Banks (R-IN), Barbara Lee (D-CA), and French Hill (R-AK).

If passed, the REAL Act would reverse the 1994 Pell grant ban, thus finally unlocking financial aid for men and women in the nation’s prisons. (Federal legislators also have the opportunity to reinstate Pell Grants by reauthorizing the Higher Education Act.) The REAL Act’s supporters include such organizations as the American Bar Association (ABA), the American Council on Education, the Association of American Colleges and Universities, the American Correctional Association, the Equal Justice Initiative, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and more.

In its own letter of support for the bill, the ABA noted that in 2013, the RAND Corporation performed a deep analysis of data from multiple studies, and emerged with the firm conclusion that “correctional education programs decrease recidivism and increase ex-offender employability.” Specifically, the RAND report found that people who participated in prison education programs were 43 percent less likely to be locked up again within three years of release than their peers who did not participate in education programs.

People who have been in prison are far less likely to complete college—8 times less likely, in fact—than their non-justice-system-involved peers, according to a report from Prison Policy Initiative, the third in a series exploring the difficulties people face while trying to access housing, employment, and education after incarceration. While 29 percent of Americans complete a college degree, less than 4% of formerly incarcerated people hold a degree.

Yet approximately 64 percent of imprisoned adults have achieved a high school diploma or GED, and are thus eligible to enroll in college, according to a report from the Vera Institute of Justice and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. Further, the Vera Institute suggests that as many as 463,000 state prisoners are eligible for Pell assistance. The report also notes that expanding access to post-secondary education in prison would increase employment rates and earnings among the formerly incarcerated. If half of Pell-eligible people participated in higher education behind bars, formerly incarcerated workers would see a $45.3 million increase in combined earnings during the first year after release from prison, according to Vera.

At the same time, that 50 percent participation rate could reduce states’ spending on incarceration by an estimated $365.8 million per year, the report states.

And rolling back the prison Pell ban would not overload the system or reduce non-incarcerated students’ access to the grants, according to Vera: even if every person in prison eligible to access the grants did so — a “virtually impossible scenario” — Pell Grant costs would “rise less than 10 percent.”

As Congress ponders the REAL Act and reauthorizing the Higher Education Act this year, calls for bringing Pell Grants back to prisons nationwide have continued to pour in.

Earlier this month, the National District Attorneys Association — the largest prosecutors’ association in the U.S. — released a letter officially endorsing the REAL Act, urging Congress to “fully restore federal Pell grant eligibility for prisoners” as a logical “second step following implementation of the FIRST Step Act” that will “continue ongoing efforts to reduce recidivism while improving outcomes for individuals released from prison.”

It is false economy not to offer Pell Grants to people who are incarcerated. Nearly all will be released at some point. Ensuring that they have rehabilitation, education, and life/job skills programs helps reduce the recidivism rate.