Editor’s note: Whatever you do or don’t think about the controversial and complex case of the Menendez Brothers, a look at their recent bid for parole opens the door to an examination of how well or poorly our systems of prison discipline presently work. So read on!

****

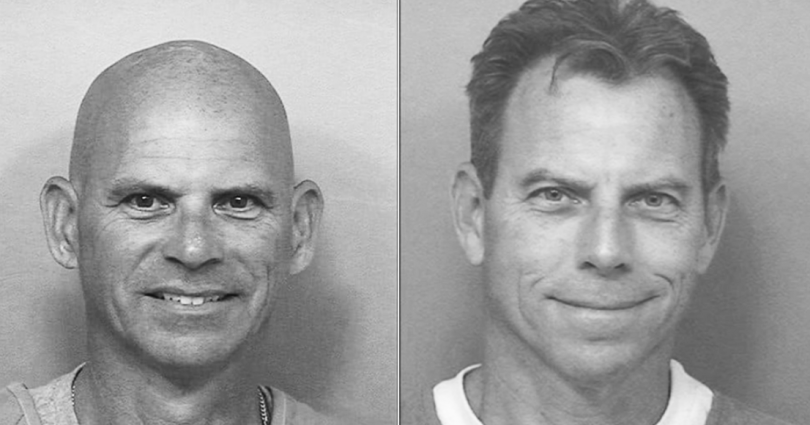

Erik and Lyle Menendez came before the California Board of Parole in individual hearings on August 21 and 22, respectively, just slightly over four months ago.

Although the brothers faced two different parole boards, the outcomes were the same.

Both were denied a chance to go home under supervision — for now.

Once impossible altogether, because the brothers were sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for killing their parents, Jose and Kitty Menendez, these hearings before California’s Board of Parole were scheduled after a ruling was handed down this past spring by Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Michael Jesic, who reduced the brothers’ sentences from life, to 50 years to life, a reduction that immediately made the brothers eligible for what is known as discretionary release.

While not the only factor, a major factor in each of the decisions to deny the brothers parole were their disciplinary records inside prison.

Disciplinary records are hardy ever adversarially tested

Over 50 years ago, in the Supreme Court case known as Wolff v. McDonnell, an inmate of the Nebraska State Penitentiary filed a class action lawsuit, on behalf of himself and his fellow inmates, alleging that The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The nation’s highest court disagreed. Writing for the six-Justice majority, Justice Byron White granted inmates a few procedural protections, including the following: written notice of charges at least 24 hours before a hearing, a written statement of the evidence against them, and the reasons for disciplinary action.

Justice White also ruled that those incarcerated must be allowed a hearing with an opportunity to present their own evidence and call witnesses (unless the calling of witnesses endangers institutional safety).

The Wolff decision may seem reasonable, but those “rights” are meaningless in prison where an inmate cannot control whether another inmate can attend a hearing or whether they will be retaliated against.

To make matters worse, the Wolff decision specifically carved away the right to confront or cross-examine adverse witnesses — namely the people accusing them — and the right to counsel.

In other words, the Wolff ruling so limited due process rights for prisoners that those constitutional rights were almost non-existent.

Eleven years after Wolff, the Supreme Court diminished prisoner protections still further:

Instead of using the usual standard of evidence in civil court matters — “a preponderance of evidence”— the Court said that only “some evidence” is required to sustain an individual’s prison disciplinary findings.

This standard of evidence, or lack thereof, gets woven into virtually every decision regarding whether or not to parole a person.

It underpins the discipline system that is often the gateway to the controversial use of solitary confinement. In addition, disciplinary records determine where prisoners reside within prisons, and can render him or her ineligible for certain rehabilitative programming so little to no evidence against a prisoner is enough to upend his or her life.

Over 50 years ago, in the Supreme Court case known as Wolff v. McDonnell, an inmate of the Nebraska State Penitentiary filed a class action lawsuit, on behalf of himself and his fellow inmates, alleging that The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services violated the due process Clause of the 14 Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

The nation’s highest court disagreed. Writing for the six-Justice majority, Justice Byron White granted inmates a few procedural protections, including the following: written notice of charges at least 24 hours before a hearing, a written statement of the evidence against them, and the reasons for disciplinary action.

Justice White also ruled that those incarcerated must be allowed a hearing with an opportunity to present their own evidence and call witnesses (unless the calling of witnesses endangers institutional safety).

The Wolff decision may seem reasonable, but those “rights” are meaningless in prison where an inmate cannot control whether another inmate can attend a hearing or whether they will be retaliated against.

To make matters worse, the Wolff decision specifically carved away the right to confront or cross-examine adverse witnesses — namely the people accusing them — and the right to counsel.

In other words, the Wolff ruling so limited due process rights for prisoners that those constitutional rights were almost non-existent.

Eleven years after Wolff, the Supreme Court diminished prisoner protections still further:

Instead of using the usual standard of evidence in civil court matters — “a preponderance of evidence”— the Court said that only “some evidence” is required to sustain an individual’s prison disciplinary findings.

This standard of evidence, or lack thereof, gets woven into virtually every decision whether or not to parole a person. It underpins the same discipline system that is also often the gateway to the controversial use of solitary confinement. Disciplinary records determine where prisoners reside within prisons, and can render him or her ineligible for certain rehabilitative programming so little to no evidence against a prisoner is enough to upend his or her life.

These same inexact records can also be the difference between life and death, when prosecutors present them as aggravating factors in the penalty phase of a death penalty case.

The Write-up problem

Nearly a decade ago, in 2016, the Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted a Survey of Prison Inmates, compiling what is still the most recent national “cross-sectional” survey of people in state prisons and federal lock-ups.

In the 2016 survey, more than half (53%) of those reported being written up or found responsible for at least one rule violation in the previous year alone.

Nine percent (9%) of those surveyed reported receiving a “major” violation during the period surveyed, meaning they’d been written up for the most serious disciplinary offenses, as opposed to minor write-ups for more trivial transgressions.

Yet, as it turned out, these write-ups didn’t necessarily mean the people who were on the receiving end of the paperwork broke any rules.

About 50% of major discipline reports are “bogus,” according to Daniel Manville, Clinical Professor of Law at Michigan State University, author of the Disciplinary Self-Help Litigation Manual, a book that helps prisoners fight disciplinary charges that result in their rights being curtailed. According to Manville’s research, minor discipline reports are even more likely to be false.

And the CDCR is quite aware of this problematic issue, reported journalist Sam Levin for The Guardian in April 2025.

Approximately 6000 drug tests yielded false positives between April and July 2024 in California correctional facilities, reported Levin. And that’s 6000 admittedly false disciplinary charges, ones that CDCR has yet to rectify.

California is not alone with this problem. According to a 2023 report released by the Office of Inspector General of New York State, over 2000 prisoners in New York facilities were punished for false drug test”

Free-world offenses v. prison offenses

Even when incarcerated people break the rules of rule breaking, prison offenses aren’t at all the same as “free world” offenses:

Keeping too much toilet paper in one’s cell is a violation. (Each person gets only two rolls. The excess is contraband). Similar rules prohibit sitting on another inmate’s bed. Walking too slowly can get someone written up.

Obviously, having no rules at all, defeats the purpose of rehabilitation. But the rules aren’t just about safety and order. Disciplinary reports have become a measuring stick for prisoner performance, as the Menendez parole hearings demonstrated. They feature so prominently in these hearings because correctional facilities lack a method to measure or quantify rehabilitation, other than recidivism rates.

And those assessments come too late.

Post Script: part 2, of this 3-part series is coming so…watch this space

*****

Author Chandra Bozelko covers the criminal justice system. She is a member of the Society of Professional Journalists’ Ethics Committee and serves as Vice President of Board of the New York Press Club. She won the 2021 Sigma Delta Chi award for Online Column Writing.

Overproduction of Lawyers, journalists , and worst of all Law professors has become a problem. The mediocre are left to go after mundane systems in order to find a niche where they can become a large fish in a small pond.

Of course nothing good will come of this, but that’s isn’t the point. There’s stories to be sold, books to be published , and attorneys hours to be billed. As Dick Jones once said, good business is where you find it.