by Jane Ellen Stevenson of Aces Too High News

“Gannett launches a network-wide push to rework its crime coverage,” writes the Poynter Institute about the changes the largest newspaper chain in the country is making in order to “make its crime coverage more enterprising, rather than reactive.”

Among the changes the Gannett newsrooms are insituting, according to Poynter, are “fewer mugshots, additional context and moving beyond police narratives.”

It’s about damn time. We advocated this more than 20 years ago, and now we go a LOT further in our suggestions to make crime reporting more relevant, less racist, and more useful to communities.

Berkeley Media Studies Group, a public health research organization, launched the Reporting on Violence project throughout California in 1997 and expanded it to interested newsrooms across the U.S. in 2001. The second edition of “The Reporting on Violence: A Handbook for Journalists” came out in 2001.

The first, which came out in 1997, was distributed to more than 950 journalists and 100 newsrooms. I wrote the handbooks. Dr. Lori Dorfman, BMSG’s director, edited them. Together, we led the project, which was funded by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation and The California Wellness Foundation.

The immediate response was great—we did workshops in all the major newsrooms in California. But things didn’t change the way I’d hoped. A few news organizations included a few contextual questions in their reporting from time to time, but none changed their crime reporting. The data we gathered inspired the San Jose Mercury News (more info below) to do a series on domestic violence, but despite reporters asking to develop a domestic violence beat, the editors said no.

Remarkably, the basics of crime reporting haven’t changed much since the late 1890s (essentially, the man-bites-dog approach). Why is it taking so long for this change to happen? The irony is that although change is journalism’s bread and butter, getting the journalism community to modernize is like moving a mountain with a spoon and a bucket.

I am a longtime health, science and technology journalist. When I wrote the Reporting on Violence handbook, I’d been covering the epidemiology of violence off and on for several years, after the CDC began taking the same approach to violence and violence prevention as they had with smoking and smoking prevention, and motor vehicle accidents and their prevention. I realized that my profession was part of the problem in how the general public understood violence, and I wanted to do something about it.

Now Gannett is beginning to make some rudimentary changes. After two years of experimenting in its news organizations in Rochester, NY, and Phoenix, AZ, Gannett is rolling out these revisions across its 250 newsrooms.

“Gannett’s new approach to crime coverage, editors say, will focus on offering context, identifying trends and following stories to their end,” Angela Fu wrote for the Poynter Institute in an article published on August 9 on their site. The Poynter Institute is a journalism training and professional standards organization. “Journalists across the newspaper chain, the largest in the country, have been attending trainings this summer to learn how to be more enterprising in their crime coverage, rather than reactive.”

The changes include:

- Removing mugshot galleries—photos of those arrested in the community that police departments provided to news organizations.

- No longer relying on police blotters for individual crime stories and instead focusing on trends. From the Poynter article: “For example, the Republic, which is based in Phoenix, used to report on individual pedestrian fatalities without explaining to readers why they were noteworthy, (Kim) Bui said. So the paper decided to track these incidents, leading to a piece that explores why Arizona has one of the highest rates of pedestrian deaths in the country.”

- Context!!! A sentence or two that explains why the news organization is covering an incident. For example, in a story about a child being left in a hot car, explaining how many times that has happened over the last year. This gives the community a sense of whether it’s an infrequent occurrence that needs some basic prevention work, or whether it’s part of an enormous problem that affects many people in the community.

- Using non-police sources, including victims and community members when reporting a crime. In other words, including more than the police as the “voice of authority”.

- Following the story for as long as it takes to be resolved. Normally, most crime stories aren’t followed up.

“Our goal is for the story to be fair to everyone involved and helpful — not harmful — to the communities we cover,” said P. Kim Bui, director for product and audience innovation at the Arizona Republic, a Gannett organization, in an article for the Republic. “But we can miss the mark. It’s critical for our newsroom to examine how we perpetuate myths or stereotypes because the potential for added and lasting pain is acute when we overhype or miscast details of a crime.”

And the news media has perpetuated many myths, including the myth that Black people commit most crimes, that neighborhoods of color are dangerous, that Black and brown people aren’t active in the local business community, that most Black and brown people are poor, and it’s their fault they don’t have good jobs.

Other news organizations are making a few very basic changes. The Associated Press will no longer name suspects in minor crime stories, and won’t use mug shots as a reason to post a story. The Boston Globe has Fresh Start, which allows people to submit appeals to remove their name and photo from articles.

These are minor changes, but it’s a start. And there’s so much more that a news organization can do to serve its community understand and prevent violence:

Scan the types of violence and other crime in your community to understand what crimes affects the community the most, in the trauma they cause as well as their economic cost.

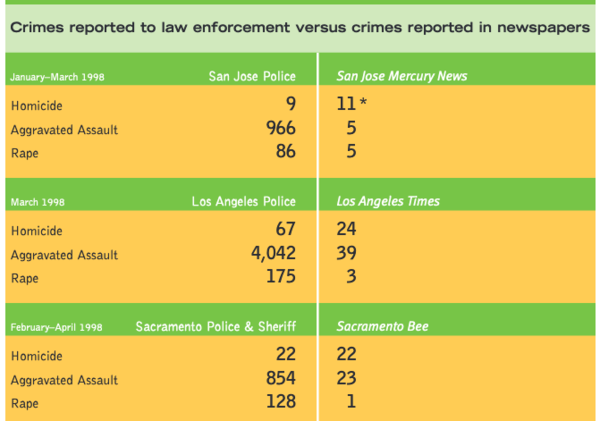

Here is some remarkable data we gathered in 1998. If we did the same in 2021, you wouldn’t see much change. Although domestic violence causes comprises most aggravated assault and causes most communities in the U.S. the most damage, economically and emotionally, it’s hardly reported. (In some communities one-third of the operating budget goes to dealing with domestic violence and its consequences. How much is domestic violence costing your city or county?) The articles about aggravated assault below did not include any reports about domestic violence.

Generally speaking, journalists report a small percentage of individual violent incidents at great length and with great precision. But, overall, the media provide an extremely inaccurate picture of crime in their communities, and how this violence affects their communities economically and emotionally. Although journalists are getting better at reporting about local violence prevention efforts, those efforts are generally not included as part of daily coverage.

The effects are profound and affect us all. Research shows that news organizations report violent crime in a way that scares people and leads them to wildly overestimate violence in their community, which leads to really bad policies. It also shows that readers and viewers feel helpless about reducing violence in their communities.

Cover the types of violence and other crime with a public health, or solutions-oriented, approach.

Here are some questions reporters can ask: How many people are dying or being injured in this type of violence? How much is this type of violence costing individuals, their families and communities, economically and emotionally? Who’s looking for a cure? What are the risk factors that contribute to this type of violence? What are city, state, national governments doing to prevent it? Is enough money being spent on research? What do people need to know to prevent the violence in their homes, neighborhoods, communities, cities, and states? What violence prevention programs are working in other neighborhoods, communities, cities, and states? Can they be emulated here? If this type of violence could be reduced by 25 percent, how much money would that save a community.

Report the ongoing status of different types of violence that affect the community the most so that a community can answer this question: Are we making progress in reducing this type of violence or not?

So far, the journalism community has not taken advantage of the new data, research and resources in this emerging field. For the most part, reporters continue to cover crime and violence by talking only to law enforcement and criminal justice officials and experts. They leave out public health experts who can provide violence prevention data, research and resources that readers and viewers can use to prevent the types of violent incidents that cause them and their communities the greatest harm.

In addition, news organizations report many fewer violent incidents than occur in their communities. “That’s what we do,” journalists respond. “We report the unusual.” Yes, but that’s not all we report. The news media regularly report the status of sports, business, political campaigns, weather and local entertainment.

By reporting the status of violence and adding information about the public health response to violence, journalists can uncover the two most hidden stories about crime in any community:

1. It’s the bulk of “ordinary” violent incidents that harm communities the most and cause cities to spend huge chunks of their budgets (hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars) on police, medical and social services.

2. People have and are developing predictable, effective methods to reduce and prevent violence.

In the second edition of the Reporting on Violence handbook, we included a sample health and safety website that showed what could be done. Keep in mind, it’s 20 years old, but the approach is still new.

Include training for all news organization staff in the science of positive and adverse childhood experiences (PACEs science).

Understanding why people do what they do can help journalists ask better questions, do better stories and help their communities solve their most intractable problems. Take this story, for example. A mother and her toddler daughter live in an apartment, and the mother’s brother moves in. While the mother’s at work, he does drugs, and a neighbor files a report with child welfare. Child welfare removes the toddler from her home and tells the mother she can be reunited with her daughter once her brother leaves or she finds a more suitable home for her daughter. A reporter who knows about the science of positive and adverse experiences (PACEs science) would ask why the child welfare agency didn’t help remove the brother or find safe housing for the mother and her daughter, instead of separating the mother and daughter, which severely traumatizes both.

The science of positive and adverse childhood experiences is at the foundation of all of our most intractable problems—arguably all violence and crime, as well as our system of incarceration, which is NOT based on PACEs science. Not only does the understanding of what happens to people in their childhoods provide the key to understanding about what they do—or don’t do—as adults, but it can help reporters understand how our systems, and systemic racism, contribute to the ongoing trauma that people experience.

With a PACEs science approach, they can also look for the solutions that are being put into place by the pioneers in this area, and, if those solutions aren’t happening in their own communities, ask “Why not?”

This story was first published in Aces Too High News, a news site that reports on research about positive and adverse childhood experiences, including developments in epidemiology, neurobiology, and the biomedical and epigenetic consequences of toxic stress.

Author Jane Ellen Stevens is the editor of ACES Too High, and founder and publisher of PACEs Connection, which comprises ACEsTooHigh.com and its companion social journalism network, PACEsConnection.com.