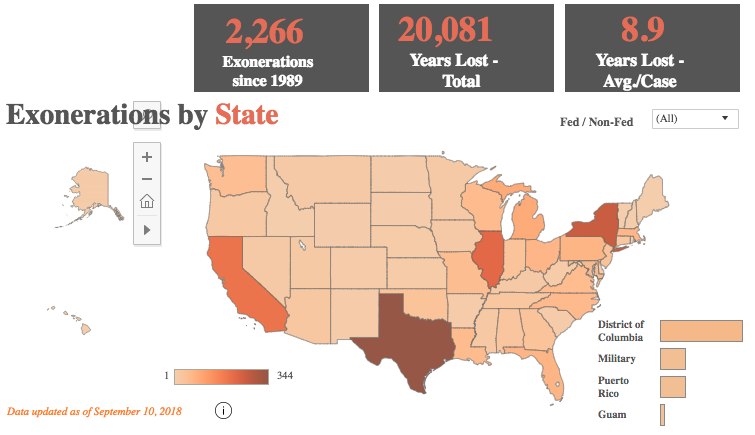

Exonerated Americans have officially spent a total of more than 20,000 years in prison for crimes they did not commit, according to a new report from the National Registry for Exonerations.

The 2,265 people exonerated since 1989 spent an average of more than 8 years 10 months behind bars, according to the report.

(The Registry is a project of the Newkirk Center for Science & Society at University of California Irvine, the University of Michigan Law School and Michigan State University College of Law.)

And while state and local governments have paid out more than $2.2 billion in post-exoneration compensation—$1.7 billion of which was the result of judgments and settlements in civil lawsuits over wrongful convictions—only 44 percent of those listed in the National Registry of Exonerations as of March 1, 2017 had received compensation for their lost years. While $2.2 billion is a hefty sum, “it’s nothing close to adequate compensation for the suffering these exonerees endured,” the report states. Moreover, “that sum provides nothing to 56% of exonerated defendants—and nothing to the many thousands of innocent defendants who spend years or decades in prison but are never exonerated.”

(One 2016 study found that California taxpayers had paid more than $282 million between 1989 and 2012 to cover incarceration expenses, legal costs, and compensation for the wrongful imprisonment of 692 people.)

Thirty-six people spent between 30 and 45 years in prison before being exonerated and released, according to the report.

Black exonerees spent 10.7 years wrongfully imprisoned, on average, while white exonerees spent an average of 7.4 years locked up. While African Americans make up approximately 12 percent of the population, they account for 46 percent of the nation’s exonerees, and endured 56 percent of all the years lost to wrongful convictions, the report says.

A Look at Last Year’s Numbers

Eighty-four of the 139 exonerations in 2017 involved misconduct on the part of police, prosecutors, or other government officials involved in the cases. That year, a record-breaking 37 people were exonerated after being wrongfully convicted based, at least in part, on mistaken eyewitness testimony. Twenty-nine more were convicted based on false confessions.

Of 2017’s 139 exonerations, 29 were for sex crimes, 41 were for for non-violent crimes, and 18 were for violent crimes other than homicide—like attempted murder, arson, and robbery. Fifty-one people were exonerated after being wrongfully convicted of murder. Four people had been sentenced to death.

Three Murder Cases

In April 2018, 68-year-old Vicente Benavides was released from California’s San Quentin State Prison after spending 25 years on death row after a jury convicted the man of fatally raping his girlfriend’s 21-month-old daughter. Experts later recanted their determinations that the toddler died of internal injuries caused by sexual abuse, and now say the child was likely hit by a car in order to sustain such fatal internal injuries. And the “rape” was likely caused by medical professionals’ attempts to insert an adult-sized catheter into the girl while trying to save her life. Benavides is the fifth death row inmate to be exonerated in California, his lawyer, Cristina Bordé, pointed out in an op-ed for the San Diego Union-Tribune. And if 2016’s Proposition 66—which speeds up the death penalty review process—had been in place while Benavides appealed his case, he “may well have been executed,” according to Bordé. “[Governor Jerry] Brown and the California Supreme Court should commute all death row sentences before the governor’s term ends in January,” Bordé wrote. “They can no longer share in the unwarranted certitude that the criminal justice system is infallible.”

Another California man, Craig Coley, spent 38 years in prison before DNA evidence cleared him of the 1978 murder of his ex-girlfriend, Rhonda Wicht and her 4-year-old son Donald, in Simi Valley. Craig was exonerated thanks to the work of Mike Bender, a retired police officer who suspected that Coley was innocent.

Kevin Cooper, a third Californian with a case that appears to be severely problematic, remains on death row. Cooper was convicted of killing a whole family, but his case is rife with problems, including prosecutorial misconduct, racial discrimination, and poor representation at trial, according to his attorneys, other legal experts, and advocates, who say the case may be “the most well-documented and well-supported matter of wrongful conviction” yet.

Last week, the LA Times editorial board called on Governor Jerry Brown, who has hinted that he may order fresh DNA testing, to hurry up and appoint a special master to review the case before Brown’s final term as governor ends. If Brown terms out before addressing the issue, “the next governor and his legal staff would probably have to start over, assuming they chose to address Cooper’s requests at all,” the editorial board wrote. “That would unjustly delay yet again the search for the truth, and the possible freeing of an innocent man.”

So, What Must the Nation Do to Reduce the Number of Wrongful Convictions?

While the Registry acknowledges that it’s likely impossible to protect all innocent defendants from convictions, “we can certainly do better than we see here:” cases marred by prosecutorial misconduct, faulty forensic science, false confessions, eyewitness misidentifications, and more. These prosecutorial failures could be greatly reduced by implementing “well-known reforms,” the report states. And while the various wrongful conviction-producing factors may seem distict from each other, “there is a common thread,” according to the report. “It costs money to do a good job of investigating and judging criminal guilt,” the report states. “Police prosecutors, defense attorneys, and courts across the country operate with inadequate funds, insufficient staff, lax supervision, and poor training.”

In other words, the report says, “You get what you pay for” in the criminal justice system. “Are we willing to pay for accuracy and fairness? Or have we concluded that sending thousands of innocent defendants to prison for tens of thousands of years is a tolerable error rate? That billions of dollars in compensation, and untold misery that can never be undone, are acceptable costs?”

Image: The National Registry of Exoneration’s interactive exoneration map.

In James seabrook I’m twenty nine I be thirty 1/21/94 I was incarcerated since 4/17/16 now I beat them 12/13/23 all charges I had 11-12019 march 2022 November 16 I had a mis trial I beat the odd 3491605359 I have to return for a 3rd cpw. Two misdemeanor trespass ammo