By Stephen Steurer

Education reduces crime, plain and simple.

The RAND Corporation underscored the positive impact of education in its 2013 review of the research reports on correctional education over the last couple of decades. Bottom line from their reports: providing education programs for incarcerated men and women significantly reduces future crime all by itself, separate from any other treatment they receive.

Combined with other effective programs, such as drug rehabilitation and mental health counseling, education can help to reduce crime and recidivism even more effectively.

RAND also demonstrated clearly that an education program pays for itself several times over. Every dollar invested in correctional education creates a return of five dollars in the reduction of future criminal justice costs.

So why are we not spending more criminal justice dollars on education? We literally spend billions on the most expensive—and least effective—option: locking folks behind bars in record numbers.

Let’s take a brief look at the large numbers of people incarcerated in the US and the cost in dollars the American taxpayer must bear. Here are some facts from research and data collected by the US Departments of Justice and Education:

Approximately 2.3 million people are incarcerated in the U.S., more than in any other developed nation by number and percentage of population;

Educational attainment levels among prisoners are far below the national average;

A lack of education is a major predictor of future crime;

Over two-thirds of those incarcerated are African American and Latino, predominately men;

95 percent of prisoners will eventually be released from prison with 600,000 released each year;

The annual budget for federal, state and local correctional agencies totals $80 billion.

Most criminologists understand the effectiveness of education and other programs but, because of the American “tough on crime’ campaign going all the way back to the late 1980s, less money is spent on rehabilitation than incarceration.

If we know this is counter-productive, why do our federal leaders, as well as many state leaders, continue to spend little for correctional education programs? Why aren’t they re-directing funding from prison beds to schools and classrooms instead of building more cells?

Research tells us that 95 percent of those incarcerated today will be released within five years. Within three years the majority of those currently behind bars will be returning to society. We are not likely to reduce sentence lengths or parole for most of these people so why don’t we take this opportunity to educate them while behind bars?

There are signs this may be finally be changing.

The current White House has shown real interest in prison reform and investment in programs to reduce recidivism. In a May 2018, a report entitled “Returns on Investments in Recidivism-Reducing Programs” by the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) reviewed and reported on research on mental health, substance abuse and education programs that are cost-effective.

Oddly, the study focused mostly on mental health and substance abuse and did not cite the extensive research report conducted by the RAND Corporation in recent years. The CEA report, however, did say, “We calculate that educational programming needs only a modest impact on recidivism rates of around 2 percent in order to be cost effective.”

The RAND study on correctional education, however, estimated the real impact to be 13 percent, much higher than the two percent needed to be effective.

Research also shows more appalling statistics about the education deficits of the prison population. Most incarcerated people are drop-outs, with more than half of them lacking a high school education. The lack of education does not in itself cause crime but it is highly correlated with other social problems such as criminal behavior, drug addiction, homelessness and poverty. Because under-educated people do not qualify for jobs with a living wage, many resort to illegal ways to support themselves.

So why not redirect more of the correctional budget currently spent on cells to fund more education programs?

It makes simple economic sense if education reduces future criminal behavior. Some advocacy groups are getting the message. For example, the conservative Koch brothers are launching Safe Streets and Second Chances, pilot programs in four states to provide career education, substance-abuse programming and counseling to 1,000 prisoners who will then be released.

This project exemplifies the bipartisan nature of the current movement for the expansion of programs to reduce recidivism and return prisoners to society as productive workers.

If programs for inmates, who lack basic academic and vocational skills, were increased and more people left prison with diplomas and career certifications, researchers could confidently predict a significant drop in future crime. Why can’t we begin remodeling our jails and prisons into educational institutions by re-purposing space with high school completion and job skills programs? If there is no appropriate space, why not move some portable classrooms behind the fence or into the yard?

Research also seems to indicate that higher levels of achievement result in even less crime. There is data indicating that inmates who participate in college commit future crime at even lower levels. Shouldn’t we support college level courses as well? For years the public has generally supported high school education for the incarcerated but not college.

Times have changed and we know that a high school education is no longer sufficient to obtain decent employment. The new standard is at least a two-year degree or a career technical certificate.

Some people believe it is too late to turn adult criminals around to lead a positive life. In fact, inmates do participate and achieve in school behind bars even if they are simply required to attend.

Testimony from former inmates clearly demonstrates how academic success changed their perception of themselves along with their own personal goals. College teachers who work in both the free community and in prisons will tell you that incarcerated students generally do much better than those in the community.

As we know in the free world it is never too late to complete school and to graduate. Lifelong learning really works for most everyone.

Maybe a little history will help explain why we are spending so little on education and more on incarceration. In 1994, with violent crime and drug abuse growing fast, federal and state governments got much tougher on crime, passing laws instituting numerous and more strict sanctions against offenders of all kinds.

Before then, inmates were eligible for Pell grants. Most states had robust college programs for inmates. In a swirl of frenzy and false accusations of fraud about fly-by-night colleges stealing federal money, Congress ended inmate eligibility for Pell grants and severely limited the federal funding levels even for high school, vocational and adult education programs as well.

When many of us were seeking support in our struggle against these foolish cuts I hoped to affect the negative attitudes in the press and contacted columnist George F. Will who agreed to visit a college classroom of Maryland prison inmates using Pell grants. In a Jan 30, 1994 article published in the Detroit Free Press and theWashington Post, entitled “Do Pell grants for prisoners work?,” Will posited that Baltimore’s streets “…may be safer than they would be if he (an inmate nicknamed “Peanut”) had not acquired some social skills with the help of his Pell grant.”

In a discussion the day before releasing the article, Will told me that he would be happy to consider revisiting the issue of correctional education when better research studies documenting the effectiveness of correctional education were available.

In the next several years better research became available, and thanks to the studies noted above that were conducted by Dr. Lois Davis and her research team at the RAND Corporation, many research studies were rigorously reviewed. The RAND publication noted above concluded that “for every dollar spent on correctional education, five dollars are saved on three-year re-incarceration costs.”

The research had meticulously reviewed every quality research study completed over the last two decades. RAND researchers wrote that the estimate of reduction was conservative and they had not been able to measure other positive results, such as job acquisition, improved family and community conditions and conditions of confinement.

What has been the impact of this study? Has the study resulted in the growth of educational budgets for the incarcerated? Have state and federal correctional education budgets begun to grow as legislators take into account the effectiveness of correctional education? Hardly!

The RAND study had actually pointed out opposite trends in funding. Federal and state budgets for correctional education have been significantly reduced since the 2008 recession, in some states by as much as 20 percent, even while prison populations continued to grow. In an age of soul searching about how to spend tax dollars wisely on cost-effective social programs with high impact, one would hope political leaders would do some serious thinking and take heed of cost-effective research by non-partisan corporations like RAND.

The Obama administration had disseminated and publicized the conclusions of the RAND study and encouraged the adoption of its recommendations. But as it has with so many other important issues, Congress has failed to act on research it originally funded.

With the notable exception of Georgia and California and a few other states, there have been little or no changes in state funding in recent years for the education of the incarcerated. Ever since the mid-1990s, most states have continued to trim education programs in prisons.

One example is California. After he was elected in 2003, California Governor Arnold Schwartzenegger’s administration decided to drastically cut correctional education programs drastically. Ironically in the last few years, partly as a result of the RAND research, California has dramatically expanded academic and career technology as well as post-secondary programs. For example, inmates also now qualify for free community college tuition while incarcerated.

Another exception is the normally conservative state Georgia. It has also taken to heart the RAND research and re-designed its entire correctional education system and also increased state funding dramatically. A post for a statewide superintendent of prison schools was created. Many more teachers were hired and programs implemented. And an investment was made in educational technology to modernize instruction and teach computer skills necessary for today’s job market.

While now admitting the RAND research is solid, most politicians continue to say no to additional funds because there are more pressing needs. Never mind that we were simply asking for redirection of current budgets, not additional outlays of public funds.

Fortunately for the US, some leaders have begun to rethink the costly and mostly ineffective “Get Tough on Crime” movement of the last 30 years. That terribly misguided effort to stem the rise of murder, violence and the drug epidemic resulted in the so-called “Three Strikes and You are Out” legislation signed by President Bill Clinton and then copied into state law by many governors and state legislators.

Literally, millions of people have been incarcerated for longer periods of time at the cost of billions of dollars with additional and terribly negative impacts on our communities and families. Only when it had become apparent that the US could no longer pay for the upkeep and maintenance of the criminal justice system have political leaders started taking a serious look at the negative results of the draconian and unjust crime reduction laws.

President George W. Bush and other political leaders had begun to realize the folly of the “Three Strikes and You Are Out” laws of the 1990s. Bush recommended the passage of the Second Chance Act of 2002 in one of his early State of the Union addresses. The momentum has slowly grown since and reformation has become a bipartisan issue. Instead of spending billions on incarceration some are beginning to look at less costly rehabilitation programs and reentry as a way to reduce future crime.

There are now strong efforts (at the federal level to rethink how we are doing correctional business. Those of us in the education, drug rehabilitation and mental health areas are working to persuade political leaders to bring about change in the laws and priorities in budgets.

Ironically, one of the most recent examples at the federal level is the fight within the White House between Attorney General Sessions and Jared Kushner over the basic philosophy of corrections and the role of prisons to build programs that reduce recidivism. An article in the New York Times illustrates the strong feelings among political leaders, particularly in the Senate, about the direction of prison reform.

Kushner, partly as a result of his own father’s incarceration in the federal Bureau of Prisons, believes in the need for more rehabilitation and reentry programs. Sessions, unfortunately, remains one of the most steadfast believers in longer sentences and tough drug laws.

Positive change can be painfully slow. However, when the US does become interested in a particular issue, it is amazing how quickly it can retool and redirect its resources. For those of us old enough to remember, we did it by putting a man on the moon when the Russians threatened US leadership in the space race.

Hopefully, we can redirect ourselves again to help change the direction of the lives of so many people returning to society after years of incarceration.

Education is not rocket science.

We already know how to teach people to read, write, do math and train for jobs. For the sake of the incarcerated and, literally, for our own health and safety, let’s build and open more school programs in our prisons and jails. Education does reduce recidivism!

Chief Justice Warren Burger said it best, in a 1987 speech to the American Bar Association:

“We must accept the reality that to confine offenders behind walls without trying to change them is an expensive folly with short term benefits — winning battles while losing the war. It is wrong, it is expensive, it is stupid.”

Finally, I hope that since we now have the solid research George Will asked for, he might consider looking at correctional education programs again, take to heart the RAND conclusions, and write a follow-up to article about “Peanut”.

We continue to need serious political writers, both liberals and conservatives, to urge government and courts to get really “tough on crime” and sentence criminals to do their time in school to straighten out their lives.

We need to literally “throw the book at them.”

This story originally appeared on The Crime Report.

Stephen J. Steurer, Ph.D, is currently the Reentry Advocate for the non-profit CURE National, one of the founders of the non-profit Maryland Correctional Education Enhancement Associates, the volunteer Education/Reentry Coordinator at the Howard County Detention Center in Maryland , and a consultant to the Council of State Governments Justice Center. He has served as a consultant to the Vera Foundation for Pathways post-secondary education project in New Jersey, North Carolina and Michigan, to the RAND Corporation on evaluation of correctional education programs, and as Executive Director of the Correctional Education Association.

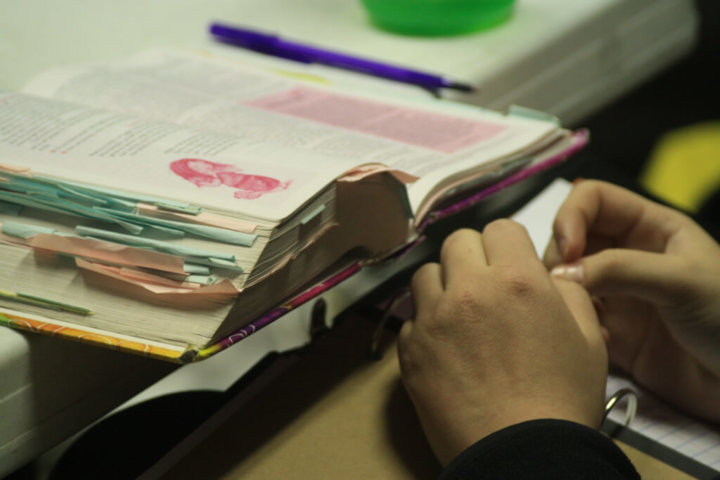

Photo by Scott Barkley via flickr