An Urban Institute report released this month makes the case for reforming sentencing and parole policies for violent crimes, not just low-level offenses.

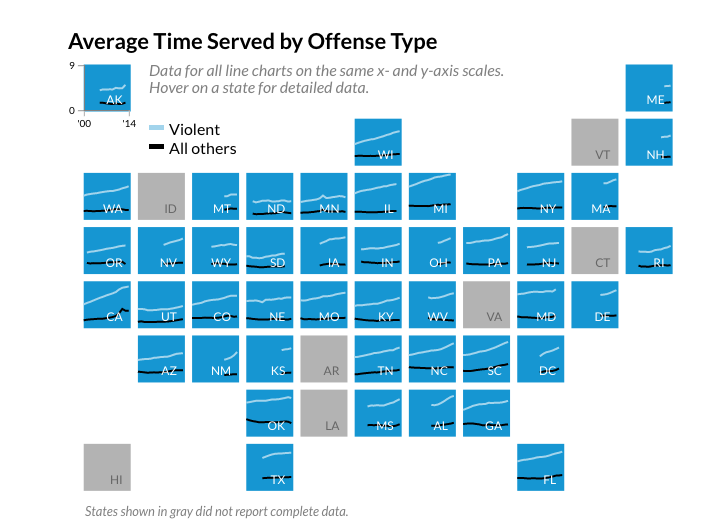

The report revealed that overall, people convicted of crimes are spending more time in prison, and the longest prison terms are growing even longer (especially in California). Moreover, violent crimes account for the majority of the increases.

These increases are due to laws and policies enacted during the tough-on-crime decades that were meant to keep people behind bars for longer––effects still felt today. And while much of the (bipartisan) reform efforts have focused on outsized sentences for non-violent drug offenses, in most states, researchers found that the largest increase in time behind bars was “mostly—if not entirely—driven by an increase in time served for violent crimes.”

People accused of violent crimes have largely been left out of the sentencing reform conversation. Yet, prisoners serving time for violent offenses comprise more than half of states’ prison populations. People who have committed violent crimes also account for the majority of people serving long prison sentences.

“Long-term incarceration fails to hold people accountable for their crimes, motivate them to make

positive change, address victims’ needs, or even deter crime,” the report states.

The researchers looked at the national time served data from a different direction than usual. They used data from yearly prison population snapshots—looking at how long current prisoners had been behind bars. This way, researchers could include data on people who otherwise would likely not be included in a study examining time served. Generally, researchers measure time served via the average length of prison terms for everyone released in a particular year. This leaves out people who are serving long-term sentences.

The researchers looked at the top 10% of the longest prison terms in each state, as well as the populations serving sentences of 10 years or more. Both groups’ sentences have been expanding in number and length.

States—Particularly CA and MI—See Time Served Skyrocket

Only 43 states (and DC) sent complete data to the National Corrections Reporting Program, but in all 44, the average time served has risen among state prisoners.

In 35 states, at least 1 in 10 prisoners have served 10 years or more, according to the report.

California and Michigan had the highest numbers, with nearly one-fourth of people have served at least a decade in prison. In California, the high percentage of long sentences is not surprising because of recent sentencing reform regarding low-level offenders. In 2011, prison realignment (AB 109) transferred the incarceration burden for certain low-level offenders away from the California’s state prison system, and into the state’s 58 counties. AB 109 “radically shift[ed] the makeup of [California’s] prisons toward people with more serious convictions,” the report states. Then, in 2014, Proposition 47 reduced six low-level drug and property felonies to misdemeanors, which carry a sentence of up to 1 year in jail.

Still, California prisons experienced a 134.9% increase in time served—from an average of 2.9 years in 2000, to 6.8 years in 2014.

CA has the highest percentage of women serving the longest sentences, as well—15.4% in 2014, compared with 3.6% in 2000.

The number of people serving sentences of at least 10 years more than doubled between 2000 and 2014 in at least 11 of the states, including CA and MI.

In those two states, the 10% of people serving the longest sentences served an average of 18.3 years in 2014. In CA in 2000, that number was just 5.5 years, and in MI, 5.6 years.

While the rate of incarceration among black people has decreased in the last 10 years, in most of the states, racial disparities remain particularly high among people serving the longest 10% of prison sentences.

In all but 9 of the states, the disparities among these longer sentences were more pronounced than in the overall prison population.

Nationally, nearly two out of five of the people serving the longest prison sentences were convicted under the age of 25. One in five people in prison for at least 10 years was a black man incarcerated before age 25.

“Young adults, like adolescents, are more amenable to change. Often, people who engage in risky behavior or in crime as adolescents or young adults…naturally age out of that,” said UI’s Samantha Harvell. “So I think it’s an important time period for addressing and rethinking our response to young adults both for their benefit [and] society at large.”

What Long Term Incarceration Doesn’t Do

The report points out that most long-term incarceration does not help crime victims, many of whom support shorter prison sentences along with boosted funding for crime prevention and rehabilitation services.

And people who commit crimes, were often first victims themselves. “An enormous percentage of people who are in prison for violent crimes were victims and never got any kind of treatment or support,” said Liz Gaynes of the Osborne Association, a reentry-focused nonprofit. “That doesn’t give them a license to kill, but it also doesn’t give us a license to have it turn out that the day you become a perpetrator, you cease being a victim.” Those victims, particularly in poor and minority communities, “never ever received any kind of support or treatment,” added Gaynes. “All that stuff we say that victims should get, they never got.”

Extended prison terms don’t serve to hold inmates accountable for their crimes, either, the report argues.

“Probably 90 percent of the guys in prison, once they are convicted, they never have any reason to think about the harm they committed against their victim,” said Howard Harris, a man who spent 40 years behind bars. “They never take the time to think about how much harm they committed against their victim unless they’re exposed to a program by which they can do it.”

Long-term prisoners deserve a meaningful chance of release, the report adds.

“I just want to mow the grass and walk the dog. I tell people all the time [that] I just love being a square,” said Stanley Bailey, who served 36 years in prison. “I just think that it’s important that the general public know that we’re not all monsters, that the majority of us coming out just want to lead a normal, productive life and treat the people around us well and just get on with our lives and go on. Given half a chance and a little bit of support and direction—-man, that’s all they want.”

The Recommendations

The report recommends 10 policy changes for states, like investing in specialized reentry programs for individuals who have served long prison terms.

“Prison is not geared no more towards long-term offenders,” said Stanley Mitchell, who spent 35 years in prison. “They just house you. You’re just housed.” Most of the programs in state prisons are focused on people who are soon to be released back into their communities, Mitchell said. “In other words, there’s no reason to let no guy who got life get a GED. There’s no reason to let a guy that got life to get a work release or anything cause they’re never getting out.”

The report also recommends allowing for individualized sentencing and release decisions, and calls for presumptive parole.

Parole, according to the report, should be granted by default at the time candidates become eligible, unless they pose a threat to public safety. And geriatric and seriously ill inmates should also be paroled.

The report recommends introducing or expanding early release incentives and opportunities across states, and expanding restorative justice-based alternative courts to include violent crimes, not just low-level offenses.

Additionally, states must more fully invest in crime prevention strategies, like affordable housing, and ensuring that in communities with high crime rates, people who have experienced or witnessed violence have access to trauma-informed treatment.

“As states invest more seriously in preventing crime in innovative ways, they must first dismantle the disastrous policies that have inflicted so much damage while doing little to address the real problems of crime,” the report stated.