First Stop Parking Places for the State’s Foster Children Have to Go

by

Richard Wexler

Two sheriff’s deputies pin a girl to the ground and force her into handcuffs. She cries as deputies put her into a patrol car and drive her off. What is her crime? She allegedly threw rocks at a van while she tried to run away from the children’s shelter where she’d been forced to live.

She is ten years old.

Her story is told in “Fostering Failure,” the San Francisco Chronicle’s investigative series about such shelters, first-stop parking place warehouses for some California children taken from parents who allegedly abused or neglected them.

Other children who faced arrest at California shelters, Chronicle reporters Karen de Sá, Cynthia Dizikes, and Joaquin Palomino found, included children who smeared cake frosting on each other and children who overturned a Monopoly game.

As is obvious to everyone except, apparently, people who run shelters, such arrests add immeasurably to the trauma these children already have endured, either because they were abused in their own homes or because they were needlessly torn from their families, as often happens when family poverty is confused with “neglect.”

Shelters are dumping grounds for overloaded child welfare systems.

Sadly, stories about abuses at foster care shelters are nothing new. But there actually is a danger in focusing only on the most visible horrors at these places. It threatens to obscure the fact that the biggest abuse perpetrated by parking place shelters is their very existence.

Shelters are dumping grounds for overloaded child welfare systems. Sometimes they’re very pretty dumping grounds staffed by lots of well-meaning people. But that doesn’t change the fact that, instead of a home, with adults who commit to real, no-kidding parenting for months or years, children are cared for by employees who dispense indiscriminate pseudo-love by the shift, to whoever comes in the door. Instead of the stability that shelter defenders contend the facilities bring to the kids , children often get the equivalent of a change in foster parents every eight hours.

Shelters Are Sacred Cows

Mary Graham Children’s Shelter near Stockton, which called the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office an average of nine times a day last year.

Yet, as the Chronicle documents in an outstanding follow-up story, shelters are a sacred cow in child welfare. In California, they can’t be killed, despite evidence-backed legislation originally designed to phase them out.

Shelters are exercises in adult self-indulgence and adult self-delusion. They’re good for everyone but the children.

Wealthy donors love shelters. They can get a plaque on the wall for giving money or furniture. Volunteers love them. They can turn real children into human teddy bears who exist for the volunteers’ gratification and convenience, even as the adults convince themselves they’re helping children. When they get bored with their human teddy bears, they simply hand them back to the shift staff.

The former director of a notorious shelter in Nevada told a local television station how he loved the fact that babies and toddlers “grab my leg. They call me Mr. Lou. They tell me they love me.”

But when a young child grabs the legs of anyone who will pay him a little attention and tells him “I love you” he’s not getting better. He’s getting worse, because every time he tries to love someone, that person goes away.

In Oklahoma, a shelter volunteer talked about how when she goes to the shelter on her lunch hour, “I get my baby fix.”

In San Diego, back in 2000, an adult, apparently a shelter volunteer, wrote to the Union Tribune attacking a former foster youth for daring to sue in an effort to close that county’s shelter – where she herself had been housed.

I don’t think they think through what the child’s experience is.

Carole Shauffer, Senior Director of the Youth Law Center, told the Chronicle that when donors visit shelters, “the young children run over to them, they hug them, they want to be read to and played with, and that must gratify their egos. But I don’t think they think through what the child’s experience is. Would it be great for your child to be living with no parent whatsoever?”

But instead of facing up to the fundamental failure built into the shelter system, many shelter operators and their trade associations retreat behind rationalization.

Shelter defenders have been especially upset lately because the new California law AB403, passed in 2015, and authored by Santa Cruz Democrat Mark Stone, will modestly curb children’s’ stays in these places – cutting the maximum stay from 30 days to ten – which is at least nine days too long. (And, as the Chronicle explains, even that law was weakened by shelter operators and their powerful political allies.)

The directors of trade associations for foster care providers tell us that you have to keep children in shelters for at least 30 days, and preferably even longer, to adequately assess them in order to find kids the right family.

In a somewhat contradictory argument, they also claim shelters exist because there are no families of any kind for the children. They warn darkly of an “epic crisis” in foster parent recruitment.

No Evidence That Shelters Succeed

In 2015 & 2016, kids from the Mary Graham foster care shelter were reportedly taken to nearby San Joaquin County Juvenile Hall an average of two times a week.

Experts in child behavior will tell you that the worst possible place to accurately assess what’s really going on with a traumatized child is in the most stressful, artificial environment imaginable – an institution. That is true even when the “assessment” period doesn’t include handcuffing ten-year-olds.

“What happens when you place a lot of hurting, angry children together in a facility?”

“What happens when you place a lot of hurting, angry children together in a facility?” asks Leland Collins, former director of social services in San Luis Obispo County in the Chronicle’s follow-up story. “The big ones tend to take out their hurt on the smaller ones. The smaller ones run, and I don’t blame them because you would too.”

That’s why Collins shut down his county’s shelter in 2003. Perhaps that’s also why I have never seen any defender of shelters provide evidence that their so-called assessments lead to better placements. In contrast, an in-depth study from Connecticut found that children who went through shelters tended to have worse outcomes than those who went straight to foster homes.

As for the claim that there is no alternative, this is belied by the fact that, like San Luis Obispo, most California counties don’t use shelters. In fact, the Chronicle found that fewer than seven percent of California foster children pass through a shelter each year. It really shouldn’t be that hard to get that number down to zero.

LA Takes Too Many Kids

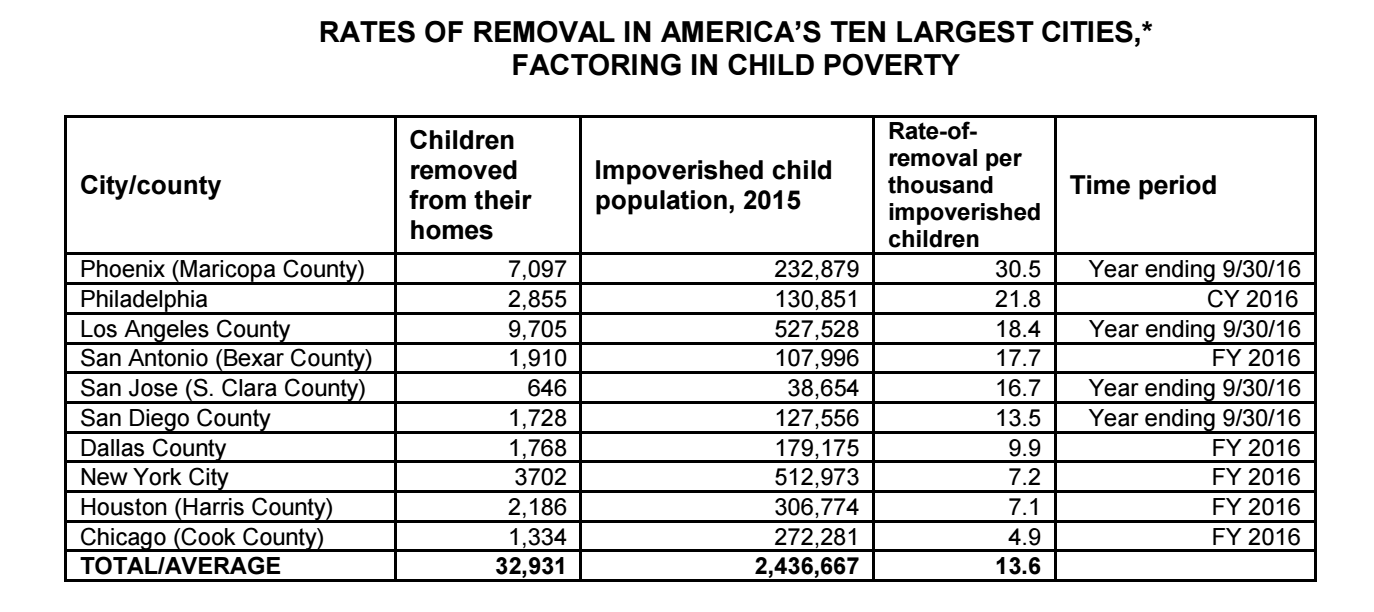

Rate of child removal for ten largest U.S. cities factoring in child poverty, courtesy of National Coalition for Child Protection Reform

Other counties, such as Los Angeles, contract with group homes to do what shelters do. But that’s because Los Angeles takes away children at a much higher rate than some other big cities.

Children are taken from their families in Los Angeles at more than double the rate of New York City

Specifically, children are taken from their families in Los Angeles at more than double the rate of New York City and more than triple the rate of Chicago, even when rates of child poverty are factored in. There is, of course, no evidence that Los Angeles children are two and three times safer than their New York and Chicago counterparts, or that LA parents are somehow two or three times as neglectful or abusive to their children.

There’s one other giveaway that shelters are for the adults, not the children: The children for whom it’s hardest to find family placements are older children. But across the nation shelters often are limited to young children. Of course, traumatized teenagers tend not to be quite so cute and huggable. They mouth off. They run away. They sometimes punch holes in walls when they are feeling desperate. So adults are less interested in “sheltering” them.

Jennifer Rodriguez, a former foster youth who now is executive director of the Youth Law Center cites another crucial problem with shelters:

If you have a shelter where you can leave youth for a long period of time while you develop another plan, workers take advantage of that. They’re overloaded and overwhelmed and have a lot of cases they’re dealing with.

In other words, if you build it, they will come. If you keep it open, they will stay. That’s why California’s shelters, and their counterparts across the country, need to be closed. Fortunately, the Chronicle reports, some in California are beginning to demand just that.

Richard Wexler is Executive Director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform.