By Sheilah Y. Kimble, California Health Report

I often quote the Langston Hughes poem “Mother to Son” and Paul Laurence Dunbar’s “We Wear the Mask,” because “Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair. It’s had tacks in it, And splinters, And boards torn up,” which became obstacles for me as I wore a “mask that grins and lies,” hiding my cheeks and shading my eyes.

The mask was a defense mechanism. What I was defending was myself. My life.

I survived verbal and physical abuse throughout my childhood and much of my early adulthood. But now, as part of my journey to heal those wounds, I am working to prevent domestic violence and child abuse because I don’t want anyone to have to go through what I did.

Domestic violence, also known as intimate partner violence, comes in many forms. And when you experience this type of trauma, it can create mental health challenges that can define your future if you let it.

It took me more than half my life to figure this out, and I am still learning. Becoming a peacemaker, always trying to avoid conflict, and becoming a people pleaser, I did not know how to define and set boundaries. I kept a smile and masked my pain with sarcasm, deflecting from the truth while minimizing the number of people I associated with.

I now realize that this was part of a defense mechanism I used to prevent myself from being hurt again.

Juliette Hagerman

Verbal abuse can create emotional fractures that break one’s spirit and self-esteem more than physical abuse. For me, it seemed as though a dark cloud hovered over me, overshadowing my life, not allowing the sunshine to force its way through.

I was never taught how to let the sunshine in. I often felt that my life had no value because of the deeply rooted trauma that I experienced.

At the age of 2, I had a childhood cancer called retinoblastoma. Family members were told that I had six months to live. I had to have what was called an eye enucleation. This was the surgical removal of my right eye.

When people feel threatened or lack a sense of security, they often attack me and make unpleasant comments about my eyes. This continues today. When in kindergarten, as a coping mechanism, I learned how to take such verbal attacks despite how badly they hurt.

Throughout school, students and teachers often made me feel less than because of my disability, including my sixth-grade teacher who demanded that I take out my prosthetic eye in front of the class to show them.

My childhood was lonely, and coming from a marginalized community outside of Los Angeles, I lacked the tools to understand healthy relationships. I experienced multiple sexual assaults — the first time when I was only 6. When I was 8, I witnessed my neighbor’s grandfather murder his wife in front of their house after a disagreement.

As I grew older, I continued to experience domestic violence in relationships. Eventually, I learned how to escape and believed I was protecting my children. But in 2011, I lost my eldest son to teen dating violence. The tragedy is that because he experienced domestic violence during his childhood, he may not have known how to protect himself from violence as an adult.

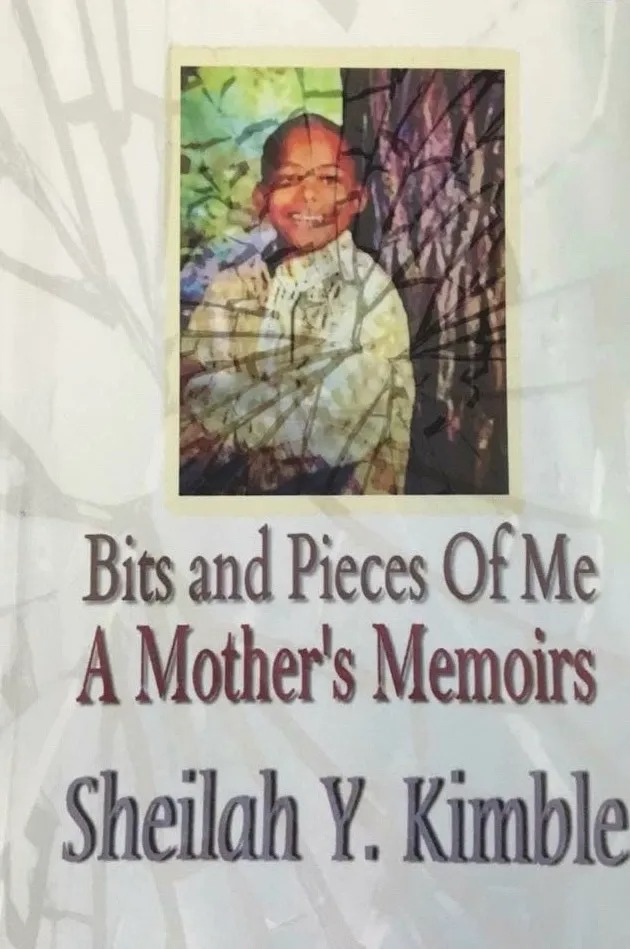

In 2008, I began writing my first book to share my story, but after the loss of my son, I had a lot more to say.

I began to write as part of my therapy and healing process, becoming a self-published author.

I continue to write today.

I also started a nonprofit organization in honor of my son, which raises awareness of how boys and men are also victims of domestic violence. I work with survivors and those who have caused harm so that they too can learn how to unlearn the cycle of abuse and negative behaviors.

Those in abusive relationships often suffer from depression, anxiety, PTSD or substance use disorders, but often don’t understand why. As I continue to educate myself and encourage others to develop healthy relationships, I’m incorporating trauma-informed practices into my work.

Ultimately, abuse is a mental health issue. Hurt people hurt people. If we can get to the root of the pain and hurt, we can often begin to heal.

I am working on letting my healing begin by sharing my story in the hope that it can help others too.

This story was produced in partnership with the California Health Report.

Sheilah Kimble is the founder of The Arthur Lee Duncantell II Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit that works to address domestic violence among boys and men, and the author of “Paralyzed in Pain” and several other books.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 for support and referrals, or text “START” to 88788.